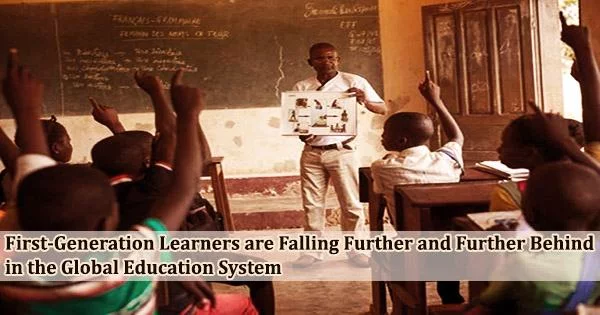

First-generation learners According to a study, a sizable portion of students around the world who are the first generation in their families to attend school are also substantially more likely to drop out of school without having acquired even the most basic literacy or numeracy abilities.

Researchers at the University of Cambridge’s Faculty of Education, Addis Abeba University, and the Ethiopian Policy Studies Institute looked into the academic development of thousands of Ethiopian pupils, including many “first-generation learners” children whose parents never attended school.

As access to education has increased, the number of these students has skyrocketed in many low- and middle-income nations in recent decades. For instance, primary school enrollment in Ethiopia has increased by nearly twofold since 2000 as a result of a wave of government education reforms and investments.

However, the current study discovered that first-generation learners struggle to advance through the educational system and are far more likely to perform poorly in math and English.

The research, which was published in the Oxford Review of Education, suggests that systems like Ethiopia’s, which until recently catered primarily to the children of an elite minority, urgently need to adapt to prioritize the needs of first-generation students, who frequently face greater disadvantages than their contemporaries.

Professor Pauline Rose, Director of the Research for Equitable Access and Learning (REAL) Centre in the Faculty of Education, and one of the paper’s authors, said: “The experience of first-generation learners has largely gone under the radar. We know that high levels of parental education often benefit children, but we have considered far less how its absence is a disadvantage.”

“Children from these backgrounds may, for example, have grown up without reading materials at home. Our research indicates that being a first-generation learner puts you at a disadvantage over and above being poor. New strategies are needed to prioritise these students if we really want to promote quality education for all.”

These findings show that schooling in its current form is not helping these children to catch up: if anything, it’s making things slightly worse. There are ways to structure education differently, so that all children learn at an appropriate pace. But we start by accepting that as access to education widens, it is inevitable that some children will need more attention than others. That may not be due to a lack of quality in the system, but because their parents never had the same opportunities.

Professor Pauline Rose

The study used data from Young Lives, an international project studying childhood poverty, to assess whether there was a measurable relationship between being a first-generation learner and children’s learning outcomes.

In particular, they drew on two data sets: One, from 2012/13, covered the progress of more than 13,700 Grade 4 and 5 students in various Ethiopian regions; the other, from 2016/17, covered roughly the same number and mix at Grades 7 and 8. They also drew on a sub-set of those who participated in both surveys, comprising around 3,000 students in total.

Around 12% of the entire dataset that includes those in school were first-generation learners. First-generation learners frequently come from less advantaged circumstances than other students, according to the researchers. For instance, they are more likely to live farther from school, come from less affluent households, or not have access to a home computer. However, first-generation learners were continuously more likely to perform poorly in school regardless of their overall circumstances.

For example: the research compiled the start-of-year test scores of students in Grades 7 and 8. These were standardised (or ‘scaled’) so that 500 represented a mean test score. According to this metric, first-generation students in math received an average test score of 470 as opposed to 504 from non-first-generation students. First-generation students’ average English score was 451, whereas their non-first-generation counterparts’ average score was 507.

The attainment gap between first-generation learners and their peers was also shown to widen over time: first-generation learners from the Grade 4/5 cohort in the study, for example, were further behind their peers by the end of Grade 4 than when they began.

The authors contend that the reasons why many low- and middle-income countries are going through a so-called “learning crisis,” where attainment in literacy and numeracy remains low despite increased access to education, may be partially explained by a general failure to take into account the disadvantages faced by first-generation learners.

The researchers assert that while this is frequently attributed to problems like large class sizes or subpar instruction, it may actually have more to do with the influx of disadvantaged children into educational systems that, up until recently, did not have to teach as many students from these backgrounds.

They assert that many teachers may require additional training to support these students, who frequently arrive at school less prepared than students from more educated (and often wealthier) households. The curriculum, assessment methods, and attainment techniques may also need to be changed to reflect the reality that primary school student populations are today far more varied than they were a generation ago in many areas of the world.

Professor Tassew Woldehanna, President of Addis Ababa University and one of the paper’s authors, said:

“It is already widely acknowledged that when children around the world start to go back to school after the COVID-19 lockdowns, many of those from less-advantaged backgrounds will almost certainly have fallen further behind in their education compared with their peers. This data suggests that in low and middle-income countries, first-generation learners should be the target of urgent attention, given the disadvantages they already face.”

“It is likely that, at the very least, a similar situation to the one we have seen in Ethiopia exists in other sub-Saharan African countries, where many of today’s parents and caregivers similarly never went to school,” Rose added.

“These findings show that schooling in its current form is not helping these children to catch up: if anything, it’s making things slightly worse. There are ways to structure education differently, so that all children learn at an appropriate pace. But we start by accepting that as access to education widens, it is inevitable that some children will need more attention than others. That may not be due to a lack of quality in the system, but because their parents never had the same opportunities.”