Antibiotics are typically used to treat C. diff infections, as they are for most infections. However, in some people, the illness can resurface at any time. More antibiotics aren’t going to help. When a doctor transplants excrement from a healthy donor into another person to restore the balance of bacteria in their gut, this is known as bacteriotherapy.

Fecal transplants could aid in the treatment of gastrointestinal infections and other ailments. The procedure is used to treat recurrent C. difficile colitis. Diarrhea, stomach cramps, and fever are all symptoms of C. difficile colitis, an antibiotic-related disease. The theory is that the donor’s excrement includes a beneficial combination of gut bacteria that can be seeded into the patient’s bowel, resulting in positive outcomes.

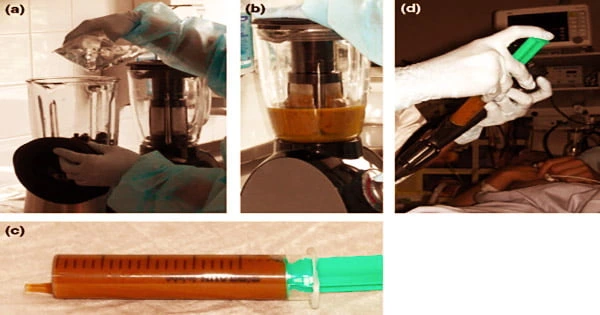

While the operation may appear to be quite unpleasant, it is not in any way unhygienic. The stool comes from a donor or a stool bank, where it has been checked for infections and processed for medical purposes. A fecal transplant introduces good bacteria from your stool into your colon. The nasty bacteria that cause disease are kept in check when you have enough healthy bacteria in your gut.

In the United States alone, C. diff caused half a million infections, 29,000 deaths, and $4.8 billion in healthcare expenses in 2011. Metronidazole, vancomycin and fidaxomycin are some of the antibiotics used to treat this infection. In 30 percent of people who have been treated with antibiotics, the infection returns within a few days or weeks of finishing the course.

Beneficial bacteria help the digestive system absorb nutrients and digest food efficiently, however some medical conditions and medicines can kill these bacteria. One technique to reintroduce them is by a fecal transplant. Antibiotics can kill the microorganisms that cause you to become ill.

They may, however, wipe away the microorganisms that keep your body in good shape. The nasty bacteria can take over if that equilibrium is disrupted. They create toxins that cause diarrhea and colitis in people.

In people who have already had recurrent C. difficile colitis, fecal transplantation is more effective than oral vancomycin in avoiding additional recurrences, according to research published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2013.

In 1958, a watershed moment in the utilization of fecal transplant, also known as fecal microbiota transplant in medical literature, occurred when clinicians tried the operation as a last-ditch, heroic treatment in four patients with life-threatening C. diff. Surprisingly, all four patients lived.

Despite the “immediate and dramatic” effects, the fecal transplant has yet to gain widespread popularity due to a common aversion to the idea of consuming stool. Fecal transplantation is not commonly undertaken for reasons other than recurrent C. difficile colitis as of 2013. More research is needed to evaluate whether fecal transplantation should be used for additional therapeutic conditions.

In 1958, a watershed moment in the utilization of fecal transplant, also known as fecal microbiota transplant in medical literature, occurred when clinicians tried the operation as a last-ditch, heroic treatment in four patients with life-threatening C. diff. Surprisingly, all four patients lived.

Despite the “immediate and dramatic” effects, the fecal transplant has yet to gain widespread popularity due to a common aversion to the idea of consuming stool. Fecal transplantation is not commonly undertaken for reasons other than recurrent C. difficile colitis as of 2013. More research is needed to evaluate whether fecal transplantation should be used for additional therapeutic conditions.

Fecal transplants date back more than 1,700 years in Chinese medicine. This practice used to entail drinking a liquid suspension of another person’s excrement, which was a highly dangerous method. Fecal transplants are sterile and safe nowadays, and there is a growing body of evidence to back them up.

The FDA considers fecal transplantation to be a “investigative novel medication” and has not approved it for public use. After one fecal transplant treatment, 70% of the patients in a small-scale 2014 experiment had no symptoms. The overall cure percentage among individuals who received numerous treatments was 90%.

Following treatment, the subjects had fewer bowel motions and rated their overall health higher. Other gastrointestinal diseases may necessitate fecal transplants, according to doctors. People with UC were given a fecal transplant using excrement from two donors mixed together in one research.

Only a month later, some patients reported decreased symptoms and less inflammation, and 15% of patients went into remission. Medical insurance usually only covers fecal transplant as a treatment for repeated, intractable C. diff infections.

Diarrhea, cramps, nausea, constipation, and flatulence have been reported as moderate side effects, while the trials conducted so far have not been large enough to discover potentially more serious problems. Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), a poorly known illness that involves a variety of digestive issues, may benefit from fecal transplants.