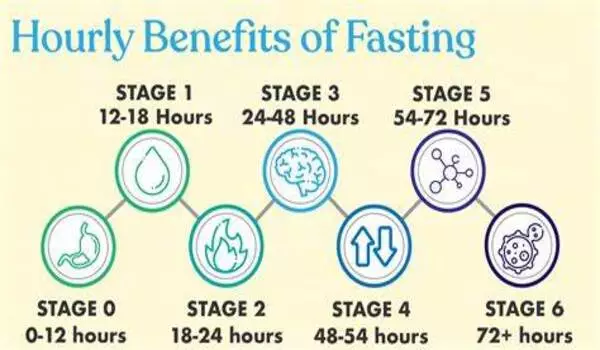

Fasting interventions, which involve alternating fasting and refeeding periods, are generally thought to improve health. However, these interventions are less effective in elderly animals. Why, one might ask. Researchers at the Max Planck Institute for Biology of Ageing in Cologne discovered that older fish deviate from a youthful fasting and refeeding cycle and instead enter a state of perpetual fasting, even when eating.

However, by genetically activating a specific subunit of AMP kinase, an important sensor of cellular energy, the benefits of refeeding after fasting in old killifish can be restored. These mutant fish had better health and longevity, indicating that both fasting and refeeding are required to confer health benefits and work via AMP kinase.

Many model organisms have already demonstrated that a reduced diet, whether through calorie restriction or fasting periods, improves health. Humans, on the other hand, find it difficult to eat less throughout their lives. Researchers introduced fasting interventions at different ages in order to find the most opportune timing for fasting, discovering that these interventions in older animals do not yield the same benefits as they do in younger animals.

Of course, we don’t yet know whether in humans the γ1-subunit is actually responsible for healthier ageing. In the next step, we will try to find molecules that activate precisely this subunit and investigate whether we can use them to positively influence ageing.

Adam Antebi

A team of researchers from Cologne, Germany, has now studied the effects of age-related fasting in killifish. Killifish are fast-ageing fish that can go from young to old in a matter of months. For a few days, the researchers either fasted young and old fish or fed them twice a day. They found that the visceral adipose (fat) tissue of old fish became less responsive to feeding. “The adipose tissue is known to react most strongly to variations in food intake and has an important role in metabolism. That’s why we looked at it more closely,” explains Roberto Ripa, lead author of the study.

Alternation between fasting and eating is crucial

The inability of old fish to respond to the feeding phase resulted in a permanent state of fasting in their fat tissue: energy metabolism is shut down, protein production is reduced, and tissue is not renewed. “We assumed that old fish would be unable to transition to fasting after feeding.” Surprisingly, the old fish were in a constant fasting state, even while eating food,” says Adam Antebi, Director of the Max Planck Institute for Biology of Ageing and study leader.

Adipose tissue in a permanent fasting state

When the researchers looked more closely at how the fatty tissue of the old fish differed from that of the young, they came across a specific protein called AMP kinase. This kinase is a cellular energy sensor, and is made up of different subunits, of which the activity of the γ1 subunit decreases with age. When the scientists increased the activity of this subunit through genetic modification, the fasting-like state was counteracted and the old fish were healthier and even lived longer.

Human ageing

Interestingly, a link was also found between the γ1-subunit and human ageing. Significantly lower levels of the particular subunit were measured in samples from elderly patients. In addition, it was possible to show in the human samples: the less frail a person is in old age, the higher the level of the γ1-subunit.

“Of course, we don’t yet know whether in humans the γ1-subunit is actually responsible for healthier ageing. In the next step, we will try to find molecules that activate precisely this subunit and investigate whether we can use them to positively influence ageing,” explains Adam Antebi.