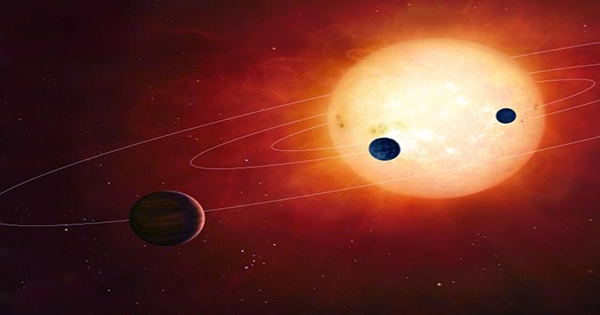

Thousands of exoplanets — planets that orbit a star outside of our Solar System — have already been discovered, and many of them have the potential to support life. According to a bizarre new notion, exoplanets two to four times the size of Earth, dubbed “sub-Neptunes,” are more likely to be water worlds than gas dwarfs, with seas so deep they beyond comprehension.

According to Gizmodo, instead of being a few kilometers deep like Earth’s seas, Harvard researcher Li Zeng believes these extraterrestrial oceans could be “hundreds or thousands of kilometers” deep. “Unfathomable. Bottomless. “Extremely deep.” The new study, which was published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, employed a complex computer model to analyse data acquired by NASA’s Kepler Space Telescope and the European Space Agency’s Gaia space telescope.

The findings are astounding: some exoplanets may have “as much as 50% water,” according to the researchers. That’s a lot more than the 0.02 percent of the planet’s mass that water makes up on Earth. In fact, the pressure would be so extreme that much of the water would freeze to hard ice. In a 2018 press release, Zeng noted, “It was a tremendous surprise to learn there must be so many water-worlds.”

Scientists have reason to assume that so-called water worlds—exoplanets whose entire surface is covered by a single massive ocean—are common throughout the cosmos. However, a new computer simulation reveals that water worlds are not only common, but also teeming with water on massive dimensions. Consider oceans with depths of hundreds, if not thousands, of kilometers. The emerging case that water worlds are a widespread characteristic of the Milky Way is bolstered by new study published today in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Harvard University astronomer Li Zeng and his colleagues presented new data using computer simulations showing that sub-Neptune-sized planets, defined as planets with radii of two to four times that of Earth, are more likely to be water worlds than gas dwarfs with thick atmospheres, as previously thought. To be clear, water worlds, also referred to as ocean worlds, are still speculative.

Unless we count Jupiter’s moon Europa and Saturn’s moon Enceladus, which are both thought to contain global oceans encased in an icy crust. Water worlds, according to planetary formation models, are genuine and presumably quite numerous. According to research published in 2017, the majority of habitable Earth-like planets are likely to be water worlds.