In the face of climate change, a series of studies on endangered species that live on the Vietnam-China border highlight the growing necessity of transboundary conservation efforts. Many plant and animal species are migrating away from their usual habitats as the world warms, raising the risk of local and global extinction.

Transboundary conservation refers to countries that share natural resources cooperating to sensibly manage them for the common good. It may appear to be a no-brainer, but it’s not as simple as it appears when important resources, habit change, and politics are involved.

A special issue of the journal Frontiers of Biogeography co-edited by Mary Blair, Director of Biodiversity Informatics Research at the American Museum of Natural History, emphasizes the importance of strategic, coordinated approaches to managing transboundary species and landscapes in preventing biodiversity loss.

“Biodiversity is undergoing dramatic loss on the global level, and we know that it is essential to human health and wellbeing and that one of the most complex and challenging threats to biodiversity is climate change,” said Blair, who works in the Museum’s Center for Biodiversity and Conservation and co-edited the special issue along with collaborators Minh Le from Vietnam National University and Ming Xu from Henan University in China.

“There’s an urgent need for more information about how climate change is already affecting the distributions of key endangered species and habitats to inform conservation action planning, especially in areas where there may be limited capacity or resources for management, such as Southeast Asia.”

There are more than 200 examples of transboundary conservation activities today, ranging from informal agreements to formal treaties between governments. Ecological benefits are included in the value of transboundary conservation, as well as increased socioeconomic resilience and improved political relations.

Over half of all terrestrial birds, animals, and amphibians have global distributions that straddle national boundaries. Border infrastructure construction and a lack of coordination of conservation initiatives on both sides of the border may endanger these species, in addition to challenges such as deforestation and poaching.

Borders often exemplify complex sociopolitical contexts and histories between countries. So conservation scientists, practitioners, and managers have an obligation to understand those contexts and know how they relate to our work and the goals of conservation. As global changes, including climate change, continue, we will have to increasingly work across borders to achieve biodiversity conservation goals and to do better science.

Mary Blair

Climate change is anticipated to heighten these dangers. According to a recent study, by the 2070s, most climatically favorable habitat for around one-third of mammalian and avian species will have relocated to a different country.

Blair, Le, and Xu initiated a research focused on a suite of ecologically and culturally important species that dwell near the China-Vietnam border and are threatened by climate change in 2018 with support from the Prince Albert II of Monaco Foundation.

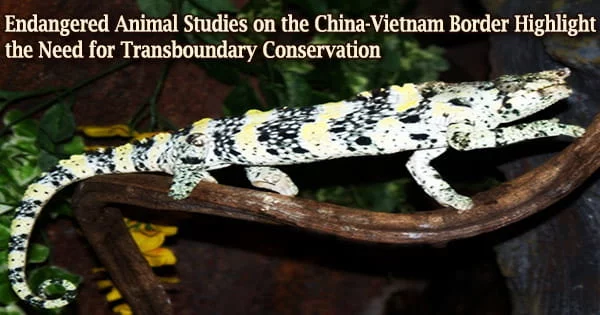

The Cao Vit gibbon, one of the world’s most endangered animals, is found in only one small forest patch; Magnolia grandis, one of the world’s most endangered trees, has a total population of fewer than 120 adult trees; and the Francois’ langur, a monkey that thrives in a special type of forest that grows over limestone.

“Our analyses show that suitable habitat for species like the Cao Vit gibbon and the Owston’s civet will significantly shrink and become highly fragmented, whereas habitat for the endangered crocodile lizard will substantially shift under future climate scenarios. The results of the study will play a crucial role in formulating appropriate transboundary conservation measures,” said Minh Le.

“The special issue is published almost concurrently with the approval of the new Vietnam National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan, which highlights the importance of assessing the impacts of climate change on biodiversity, especially highly endangered species, in the country and designing transboundary conservation measures in collaboration with neighboring countries.”

“The project is also timely and important to China’s national biodiversity conservation plan. China is reforming its protected areas by establishing a more efficient conservation network to better protect species and ecosystems in the country, including the ‘new immigrants’ expected to arrive under future climate change,” said Ming Xu.

“Results of the project have also been used to support China’s National Spatial Planning Initiative, which requires delimitation and implementation along three control lines, namely the ecological protection boundaries, permanently protected farmlands, and urban development boundaries.”

These thorough research, as well as commentary from the three editors on best practices for utilizing species distribution models (SDMs), which can predict how a species’ range might shift as a result of climate change, are included in the special journal issue.

The authors agree that SDMs should be designed cooperatively with all stakeholders from the start, especially in transboundary conservation contexts.

“Borders often exemplify complex sociopolitical contexts and histories between countries,” Blair said. “So conservation scientists, practitioners, and managers have an obligation to understand those contexts and know how they relate to our work and the goals of conservation. As global changes, including climate change, continue, we will have to increasingly work across borders to achieve biodiversity conservation goals and to do better science.”

The Prince Albert II of Monaco Foundation provided funding for this study. Cologne Zoo, Fauna and Flora International, and the Center for Plan Conservation, among others, provided technical assistance.