Elections frequently result in significant policy changes in emerging nations where political party differences are great, even when the current government remains in place. All firms have difficulties as a result of this electoral uncertainty, but a recent study published in the Global Strategy Journal reveals that, contrary to popular opinion, state-owned companies face additional difficulties.

Election years can be particularly challenging for businesses, even those with indirect investments in their home governments, to preserve their global interests.

“Multinationals with indirect ownership are less likely to internationalize in an election year, and when they do, they implement more flexible strategies than fully private companies,” says Rodrigo DeMello, an associate professor of management at Bentley University.

DeMello, and his co-authors Marina Gama and Oliver Bertrand of Fundação Getulio Vargas in Brazil, and Marie-Ann Betschinger of HEC Montréal, describe indirect ownership as institutional investment from entities like public banks or government-controlled pension funds.

This type of indirect state investment exists in democracies all around the world, including Australia, Canada, France, and the United States. However, it creates pronounced vulnerabilities for companies based in countries with newer democracies.

“The role of the home government supporting its multinationals is well documented; however, multinationals from emerging countries face potential disruption of this support in election years,” says Gama.

Indirect state ownership can help companies access subsidized finances, privileged information, and diplomatic networks. State-owned shareholders, however, have the power to withdraw state favoritism during election years or use it to redirect funds away from foreign investments at these corporations.

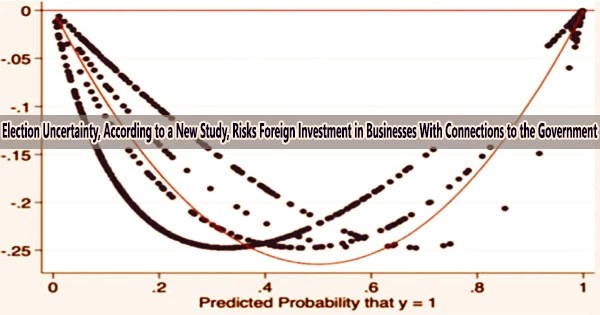

The authors examined 89 multinational companies in Brazil from 2000 to 2012 to see how three elections changed the international strategies for organizations with indirect state ownership.

Organizations with indirect state ownership are 20% less likely than private enterprises to grow internationally during election years. Additionally, they are 10% more likely to establish a completely owned subsidiary than a partially held one, and they are approximately 40% more likely to build foreign service subsidiaries than manufacturing facilities.

“Multinational organizations with indirect state ownership are not only less likely to internationalize during elections, but also more likely to hedge on flexible investments across their borders,” says Bertrand. “When they do invest, they want complete control over their investments.”

The study emphasizes the need for managers in developing democracies to incorporate political elections into their strategic planning by demonstrating that state ownership does not ensure resource continuity. It offers insight to those in more developed democracies as well.

Even though the study only looked at multinational corporations in Brazil, the authors find that industrialized democracies are increasingly experiencing the political instability and stark ideological disparities they describe.