Introduction:

International trade is, in principle, not different from domestic trade as the motivation and the behavior of parties involved in a trade do not change fundamentally regardless of whether trade is across a border or not.International trade is the exchange of capital, goods, and services across international borders or territories. In most countries, such trade represents a significant share of gross domestic product (GDP). While international trade has been present throughout much of history its economic, social, and political importance has been on the rise in recent centuries.

Economics of International Trade

International economics is concerned with the effects upon economic activity of international differences in productive resources and consumer preferences and the international institutions that affect them.

Exchange rates come in two forms:

- “Floating”—here, currencies are set on the open market based on the supply of and demand for each currency. For example, all other things being equal, if the U.S. imports more from Japan than it exports there, there will be less demand for U.S. dollars (they are not desired for purchasing goods) and more demand for Japanese yen—thus, the price of the yen, in dollars, will increase, so you will get fewer yen for a dollar.

- “Fixed”—currencies may be “pegged” to another currency (e.g., the Argentine currency is guaranteed in terms of a dollar value), to a composite of currencies (i.e., to avoid making the currency dependent entirely on the U.S. dollar, the value might be 0.25*U.S. dollar+4*Mexican peso+50*Japanese yen+0.2*German mark+0.1*British pound), or to some other valuable such as gold. Note that it is very difficult to maintain these fixed exchange rates—governments must buy or sell currency on the open market when currencies go outside the accepted ranges. Fixed exchange rates, although they produce stability and predictability, tend to get in the way of market forces—if a currency is kept artificially low, a country will tend to export too much and import too little.

Trade balances and exchange rates. When exchange rates are allowed to fluctuate, the currency of a country that tends to run a trade deficit will tend to decline over time, since there will be less demand for that currency. This reduced exchange rate will then tend to make exports more attractive in other countries, and imports less attractive at home.

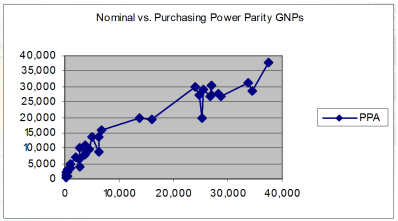

Measuring country wealth. There are two ways to measure the wealth of a country. The nominal per capita gross domestic product (GDP) refers to the value of goods and services produced per person in a country if this value in local currency were to be exchanged into dollars. Suppose, for example, that the per capita GDP of Japan is 3,500,000 yen and the dollar exchanges for 100 yen, so that the per capita GDP is (3,500,000/100)=$35,000. However, that $35,000 will not buy as much in Japan—food and housing are much more expensive there. Therefore, we introduce the idea of purchase parity adjusted per capita GDP, which reflects what this money can buy in the country. This is typically based on the relative costs of a weighted “basket” of goods in a country (e.g., 35% of the cost of housing, 40% the cost of food, 10% the cost of clothing, and 15% cost of other items). If it turns out that this measure of cost of living is 30% higher in Japan, the purchase parity adjusted GPD in Japan would then be ($35,000/(130%) = $26,923. (The Gross Domestic Product (GPD) and Gross National Product (GNP) are almost identical figures. The GNP, for example, includes income made by citizens working abroad, and does not include the income of foreigners working in the country. Traditionally, the GNP was more prevalent; today the GPD is more commonly used—in practice, the two measures fall within a few percent of each other.)

In general, the nominal per capita GPD is more useful for determining local consumers’ ability to buy imported goods, the cost of which are determined in large measure by the costs in the home market, while the purchase parity adjusted measure is more useful when products are produced, at local costs, in the country of purchase. For example, the ability of Argentinians to purchase micro computer chips, which are produced mostly in the U.S. and Japan, is better predicted by nominal income, while the ability to purchase toothpaste made by a U.S. firm in a factory in Argentina is better predicted by purchase parity adjusted income.

It should be noted that, in some countries, income is quite unevenly distributed so that these average measures may not be very meaningful. In Brazil, for example, there is a very large underclass making significantly less than the national average, and thus, the national figure is not a good indicator of the purchase power of the mass market. Similarly, great regional differences exist within some countries—income is much higher in northern Germany than it is in the former East Germany, and income in southern Italy is much lower than in northern Italy.

Political and Legal Influences

The political situation. The political relations between a firm’s country of headquarters (or other significant operations) and another one may, through no fault of the firm’s, become a major issue. For example, oil companies which invested in Iraq or Libya became victims of these countries’ misconduct that led to bans on trade. Similarly, American firms may be disliked in parts of Latin America or Iran where the U.S. either had a colonial history or supported unpopular leaders such as the former shah.

Certain issues in the political environment are particularly significant. Some countries, such as Russia, have relatively unstable governments, whose policies may change dramatically if new leaders come to power by democratic or other means. Some countries have little tradition of democracy, and thus it may be difficult to implement. For example, even though Russia is supposed to become a democratic country, the history of dictatorships by the communists and the czars has left country of corruption and strong influence of criminal elements.

Laws across borders. When laws of two countries differ, it may be possible in a contract to specify in advance which laws will apply, although this agreement may not be consistently enforceable. Alternatively, jurisdiction may be settled by treaties, and some governments, such as that of the U.S., often apply their laws to actions, such as anti-competitive behavior, perpetrated outside their borders (extra-territorial application). By the doctrine known as compulsion, a firm that violates U.S. law abroad may be able to claim as a defense that it was forced to do so by the local government; such violations must, however, be compelled—that they are merely legal or accepted in the host country is not sufficient.

The reality of legal systems. Some legal systems, such as that of the U.S., are relatively “transparent”—that is, the law tends to be what its plain meaning would suggest. In some countries, however, there are laws on the books which are not enforced (e.g., although Japan has antitrust laws similar to those of the U.S., collusion is openly tolerated). Further, the amount of discretion left to government officials tends to vary. In Japan, through the doctrine of administrative guidance, great latitude is left to government officials, who effectively make up the laws.

One serious problem in some countries is a limited access to the legal systems as a means to redress grievances against other parties. While the U.S. may rely excessively on lawsuits, the inability to effectively hold contractual partners to their agreement tends to inhibit business deals. In many jurisdictions, pre-trial discovery is limited, making it difficult to make a case against a firm whose internal documents would reveal guilt. This is one reason why personal relationships in some cultures are considered more significant than in the U.S.—since enforcing contracts may be difficult, you must be sure in advance that you can trust the other party.

Legal systems of the World. There are four main approaches to law across the World, with some differences within each:

- Common law, the system in effect in the U.S., is based on a legal tradition of precedent. Each case that raises new issues is considered on its own merits, and then becomes a precedent for future decisions on that same issue. Although the legislature can override judicial decisions by changing the law or passing specific standards through legislation, reasonable court decisions tend to stand by default.

- Code law, which is common in Europe, gives considerably shorter leeway to judges, who are charged with “matching” specific laws to situations—they cannot come up with innovative solutions when new issues such as patentability of biotechnology come up. There are also certain differences in standards. For example, in the U.S. a supplier whose factory is hit with a strike is expected to deliver on provisions of a contract, while in code law this responsibility may be nullified by such an “act of God.”

- Islamic law is based on the teachings of the Koran, which puts forward mandates such as a prohibition of usury, or excessive interest rates. This has led some Islamic countries to ban interest entirely; in others, it may be tolerated within reason. Islamic law is ultimately based on the need to please God, so “getting around” the law is generally not acceptable. Attorneys may be consulted about what might please God rather than what is an explicit requirements of the government.

- Socialist law is based on the premise that “the government is always right” and typically has not developed a sophisticated framework of contracts (you do what the governments tells you to do) or intellectual property protection (royalties are unwarranted since the government ultimately owns everything). Former communist countries such as those of Eastern Europe and Russia are trying to advance their legal systems to accommodate issues in a free market.

U.S. laws of particular interest to firms doing business abroad.

Anti-trust. U.S. antitrust laws are generally enforced in U.S. courts even if the alleged transgression occurred outside U.S. jurisdiction. For example, if two Japanese firms collude to limit the World supply of VCRs, they may be sued by the U.S. government (or injured third parties) in U.S. courts, and may have their U.S. assets seized.

- The Foreign Corrupt Influences Act came about as Congress was upset with U.S. firms’ bribery of foreign officials. Although most if not all countries ban the payment of bribes, such laws are widely flaunted in many countries, and it is often useful to pay a bribe to get foreign government officials to act favorably. Firms engaging in this behavior, even if it takes place entirely outside the U.S., can be prosecuted in U.S. courts, and many executives have served long prison sentences for giving in to temptation. In contrast, in the past some European firms could actually deduct the cost of foreign bribes from their taxes! There are some gray areas here—it may be legal to pay certain “tips” –known as “facilitating payments”—to low level government workers in some countries who rely on such payments as part of their salary so long as these payments are intended only to speed up actions that would be taken anyway. For example, it may be acceptable to give a reasonable (not large) facilitating payment to get customs workers to process a shipment faster, but it would not be legal to pay these individuals to change the classification of a product into one that carries a lower tariff.

- Anti-boycott laws. Many Arab countries maintain a boycott of Israel, and foreigners that want to do business with them may be asked to join in this boycott by stopping any deals they do with Israel and certifying that they do not trade with that country. It is illegal for U.S. firms to make this certification even if they have not dropped any actual deals with Israel to get a deal with boycotters.

- Trading With the Enemy. It is illegal for U.S. firms to trade with certain countries that are viewed to be hostile to the U.S.—e.g., Libya and Iraq.

Culture

Culture is part of the external influences that impact the consumer. That is, culture represents influences that are imposed on the consumer by other individuals.

The definition of culture offered one text is “That complex whole which includes knowledge, belief, art, morals, custom, and any other capabilities and habits acquired by man person as a member of society.” From this definition, we make the following observations:

- Culture, as a “complex whole,” is a system of interdependent components.

- Knowledge and beliefs are important parts. In the U.S., we know and believe that a person who is skilled and works hard will get ahead. In other countries, it may be believed that differences in outcome result more from luck. “Chunking,” the name for China in Chinese, literally means “The Middle Kingdom.” The belief among ancient Chinese that they were in the center of the universe greatly influenced their thinking.

- Other issues are relevant. Art, for example, may be reflected in the rather arbitrary practice of wearing ties in some countries and wearing turbans in others. Morality may be exhibited in the view in the United States that one should not be naked in public. In Japan, on the other hand, groups of men and women may take steam baths together without perceived as improper. On the other extreme, women in some Arab countries are not even allowed to reveal their faces. Notice, by the way, that what at least some countries view as moral may in fact be highly immoral by the standards of another country.

Culture has several important characteristics: (1) Culture is comprehensive. This means that all parts must fit together in some logical fashion. For example, bowing and a strong desire to avoid the loss of face are unified in their manifestation of the importance of respect. (2) Culture is learned rather than being something we are born with. We will consider the mechanics of learning later in the course. (3) Culture is manifested within boundaries of acceptable behavior. For example, in American society, one cannot show up to class naked, but wearing anything from a suit and tie to shorts and a T-shirt would usually be acceptable. Failure to behave within the prescribed norms may lead to sanctions, ranging from being hauled off by the police for indecent exposure to being laughed at by others for wearing a suit at the beach. (4) Conscious awareness of cultural standards is limited. One American spy was intercepted by the Germans during World War II simply because of the way he held his knife and fork while eating. (5) Cultures fall somewhere on a continuum between static and dynamic depending on how quickly they accept change. For example, American culture has changed a great deal since the 1950s, while the culture of Saudi Arabia has changed much less.

Dealing with culture. Culture is a problematic issue for many marketers since it is inherently nebulous and often difficult to understand. One may violate the cultural norms of another country without being informed of this, and people from different cultures may feel uncomfortable in each other’s presence without knowing exactly why (for example, two speakers may unconsciously continue to attempt to adjust to reach an incompatible preferred interpersonal distance).

Warning about stereotyping. When observing a culture, one must be careful not to over-generalize about traits that one sees. Research in social psychology has suggested a strong tendency for people to perceive an “outgroup” as more homogenous than an “ingroup,” even when they knew what members had been assigned to each group purely by chance. When there is often a “grain of truth” to some of the perceived differences, the temptation to over-generalize is often strong. Note that there are often significant individual differences within cultures.

Cultural lessons. We considered several cultural lessons in class; the important thing here is the big picture. For example, within the Muslim tradition, the dog is considered a “dirty” animal, so portraying it as “man’s best friend” in an advertisement is counter-productive. Packaging, seen as a reflection of the quality of the “real” product, is considerably more important in Asia than in the U.S., where there is a tendency to focus on the contents which “really count.” Many cultures observe significantly greater levels of formality than that typical in the U.S., and Japanese negotiator tend to observe long silent pauses as a speaker’s point is considered.

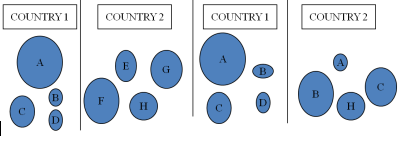

Cultural characteristics as a continuum. There is a tendency to stereotype cultures as being one way or another (e.g., individualistic rather than collectivistic). Note, however, countries fall on a continuum of cultural traits. Hofstede’s research demonstrates a wide range between the most individualistic and collectivistic countries, for example—some fall in the middle.

Hofstede’s Dimensions. Gert Hofstede, a Dutch researcher, was able to interview a large number of IBM executives in various countries, and found that cultural differences tended to center around four key dimensions:

- Individualism vs. collectivism: To what extent do people believe in individual responsibility and reward rather than having these measures aimed at the larger group? Contrary to the stereotype, Japan actually ranks in the middle of this dimension, while Indonesia and West Africa rank toward the collectivistic side. The U.S., Britain, and the Netherlands rate toward individualism.

- Power distance: To what extent is there a strong separation of individuals based on rank? Power distance tends to be particularly high in Arab countries and some Latin American ones, while it is more modest in Northern Europe and the U.S.

- Masculinity vs. femininity involves a somewhat more nebulous concept. “Masculine” values involve competition and “conquering” nature by means such as large construction projects, while “feminine” values involve harmony and environmental protection. Japan is one of the more masculine countries, while the Netherlands rank relatively low. The U.S. is close to the middle, slightly toward the masculine side. ( The fact that these values are thought of as “masculine” or “feminine” does not mean that they are consistently held by members of each respective gender—there are very large “within-group” differences. There is, however, often a large correlation of these cultural values with the status of women.)

- Uncertainty avoidance involves the extent to which a “structured” situation with clear rules is preferred to a more ambiguous one; in general, countries with lower uncertainty avoidance tend to be more tolerant of risk. Japan ranks very high. Few countries are very low in any absolute sense, but relatively speaking, Britain and Hong Kong are lower, and the U.S. is in the lower range of the distribution.

Although Hofstede’s original work did not address this, a fifth dimension of long term vs. short term orientation has been proposed. In the U.S., managers like to see quick results, while Japanese managers are known for take a long term view, often accepting long periods before profitability is obtained.

High vs. low context cultures: In some cultures, “what you see is what you get”—the speaker is expected to make his or her points clear and limit ambiguity. This is the case in the U.S.—if you have something on your mind, you are expected to say it directly, subject to some reasonable standards of diplomacy. In Japan, in contrast, facial expressions and what is not said may be an important clue to understanding a speaker’s meaning. Thus, it may be very difficult for Japanese speakers to understand another’s written communication. The nature of languages may exacerbate this phenomenon—while the German language is very precise, Chinese lacks many grammatical features, and the meaning of words may be somewhat less precise. English ranks somewhere in the middle of this continuum.

Ethnocentrism and the self-reference criterion. The self-reference criterion refers to the tendency of individuals, often unconsciously, to use the standards of one’s own culture to evaluate others. For example, Americans may perceive more traditional societies to be “backward” and “unmotivated” because they fail to adopt new technologies or social customs, seeking instead to preserve traditional values. In the 1960s, a supposedly well read American psychology professor referred to India’s culture of “sick” because, despite severe food shortages, the Hindu religion did not allow the eating of cows. The psychologist expressed disgust that the cows were allowed to roam free in villages, although it turns out that they provided valuable functions by offering milk and fertilizing fields. Ethnocentrism is the tendency to view one’s culture to be superior to others. The important thing here is to consider how these biases may come in the way in dealing with members of other cultures.

It should be noted that there is a tendency of outsiders to a culture to overstate the similarity of members of that culture to each other. In the United States, we are well aware that there is a great deal of heterogeneity within our culture; however, we often underestimate the diversity within other cultures. For example, in Latin America, there are great differences between people who live in coastal and mountainous areas; there are also great differences between social classes.

Language issues. Language is an important element of culture. It should be realized that regional differences may be subtle. For example, one word may mean one thing in one Latin American country, but something off-color in another. It should also be kept in mind that much information is carried in non-verbal communication. In some cultures, we nod to signify “yes” and shake our heads to signify “no;” in other cultures, the practice is reversed. Within the context of language:

- There are often large variations in regional dialects of a given language. The differences between U.S., Australian, and British English are actually modest compared to differences between dialects of Spanish and German.

- Idioms involve “figures of speech” that may not be used, literally translated, in other languages. For example, baseball is a predominantly North and South American sport, so the notion of “in the ball park” makes sense here, but the term does not carry the same meaning in cultures where the sport is less popular.

- Neologisms involve terms that have come into language relatively recently as technology or society involved. With the proliferation of computer technology, for example, the idea of an “add-on” became widely known. It may take longer for such terms to “diffuse” into other regions of the world. In parts of the World where English is heavily studied in schools, the emphasis is often on grammar and traditional language rather than on current terminology, so neologisms have a wide potential not to be understood.

- Slang exists within most languages. Again, regional variations are common and not all people in a region where slang is used will necessarily understand this. There are often significant generation gaps in the use of slang.

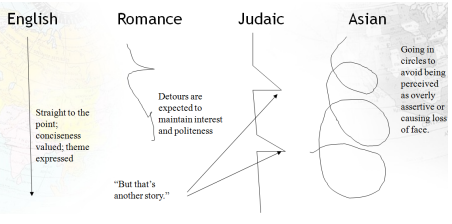

Writing patterns, or the socially accepted ways of writing, will differs significantly between cultures.

In English and Northern European languages, there is an emphasis on organization and conciseness. Here, a point is made by building up to it through background. An introduction will often foreshadow what is to be said. In Romance languages such as Spanish, French, and Portuguese, this style is often considered “boring” and “inelegant.” Detours are expected and are considered a sign of class, not of poor organization. In Asian languages, there is often a great deal of circularity. Because of concerns about potential loss of face, opinions may not be expressed directly. Instead, speakers may hint at ideas or indicate what others have said, waiting for feedback from the other speaker before committing to a point of view.

Because of differences in values, assumptions, and language structure, it is not possible to meaningfully translate “word-for-word” from one language to another. A translator must keep “unspoken understandings” and assumptions in mind in translating. The intended meaning of a word may also differ from its literal translation. For example, the Japanese word hai is literally translated as “yes.” To Americans, that would imply “Yes, I agree.” To the Japanese speaker, however, the word may mean “Yes, I hear what you are saying” (without any agreement expressed) or even “Yes, I hear you are saying something even though I am not sure exactly what you are saying.”

Differences in cultural values result in different preferred methods of speech. In American English, where the individual is assumed to be more in control of his or her destiny than is the case in many other cultures, there is a preference for the “active” tense (e.g., “I wrote the marketing plan”) as opposed to the passive (e.g., “The marketing plan was written by me.”)

Because of the potential for misunderstandings in translations, it is dangerous to rely on a translation from one language to another made by one person. In the “decentering” method, multiple translators are used. The text is first translated by one translator—say, from German to Mandarin Chinese. A second translator, who does not know what the original German text said, will then translate back to German from Mandarin Chinese translation. The text is then compared. If the meaning is not similar, a third translator, keeping in mind this feedback, will then translate from German to Mandarin. The process is continued until the translated meaning appears to be satisfactory.

Different perspectives exist in different cultures on several issues; e.g.:

- Monochronic cultures tend to value precise scheduling and doing one thing at a time; in polychronic cultures, in contrast, promptness is valued less, and multiple tasks may be performed simultaneously. (See text for more detail).

- Space is perceived differently. Americans will feel crowded where people from more densely populated countries will be comfortable.

- Symbols differ in meaning. For example, while white symbols purity in the U.S., it is a symbol of death in China. Colors that are considered masculine and feminine also differ by culture.

- Americans have a lot of quite shallow friends toward whom little obligation is felt; people in European and some Asian cultures have fewer, but more significant friends. For example, one Ph.D. student from India, with limited income, felt obligated to try buy an airline ticket for a friend to go back to India when a relative had died.

- In the U.S. and much of Europe, agreements are typically rather precise and contractual in nature; in Asia, there is a greater tendency to settle issues as they come up. As a result, building a relationship of trust is more important in Asia, since you must be able to count on your partner being reasonable.

- In terms of etiquette, some cultures have more rigid procedures than others. In some countries, for example, there are explicit standards as to how a gift should be presented. In some cultures, gifts should be presented in private to avoid embarrassing the recipient; in others, the gift should be made publicly to ensure that no perception of secret bribery could be made.

Cross-Cultural Market Research

Primary vs. secondary research. There are two kinds of market research: Primary research refers to the research that a firm conducts for its own needs (e.g., focus groups, surveys, interviews, or observation) while secondary research involves finding information compiled by someone else. In general, secondary research is less expensive and is faster to conduct, but it may not answer the specific questions the firm seeks to have answered (e.g., how do consumers perceive our product?), and its reliability may be in question.

Secondary sources. A number of secondary sources of country information are available. One of the most convenient sources is an almanac, containing a great deal of country information. Almanacs can typically be bought for $10.00 or less. The U.S. government also publishes a guide to each country, and the handbook International Business Information: How to Find It, How to Use It (HF 54.5.P33 [1998] in the Reference Department of the Gelman Library), provides leads on numerous sources by topic. Stat-USA, a database compiled by the U.S. Department of Commerce and available through the Gelman Library (you can access it through the “Links” section of my web-site), contains a great deal of statistical information online. Excellent full text searchable indices to periodicals include Lexis-Nexis and RDS Business and Industry, also available through Gelman.

Several experts may be available. Anthropologists and economists in universities may have built up a great deal of knowledge and may be available for consulting. Consultants specializing in various regions or industries are typically considerably more expensive. One should be careful about relying on the opinions of expatriates (whose views may be biased or outdated) or one’s own experience (which may relate to only part of a country or a certain subsegment) and may also suffer from the limitation of being a sample of size 1.

Hard vs. soft data. “Hard” data refers to relatively quantifiable measures such as a country’s GDP, number of telephones per thousand residents, and birth rates (although even these supposedly “objective” factors may be subject to some controversy due to differing definitions and measurement approaches across countries). In contrast, “soft” data refers to more subjective issues such as country history or culture. It should be noted that while the “hard” data is often more convenient and seemingly objective, the “soft” data is frequently as important, if not more so, in understanding a market.

Data reliability. The accuracy and objectivity of data depend on several factors. One significant one is the motivation of the entity that releases it. For example, some countries may want to exaggerate their citizens’ literacy rates owing to national pride, and an organization promoting economic development may paint an overly rosy picture in order to attract investment. Some data may be dated (e.g., a census may be conducted rarely in some regions), and some countries may lack the ability to collect data (it is difficult to reach people in the interior regions of Latin America, for example). Differences in how constructs are defined in different countries (e.g., is military personnel counted in people who are employed?) may make figures of different jurisdictions non-comparable.

Cost of data. Much government data, or data released by organizations such as the World Bank or the United Nations, is free or inexpensive, while consultants may charge very high rates.

Issues in primary research. Cultural factors often influence how people respond to research. While Americans are used to market research and tend to find this relatively un-threatening, consumers in other countries may fear that the data will be reported to the government, and may thus not give accurate responses. In some cultures, criticism or confrontation are considered rude, so consumers may not respond honestly when they dislike a product. Technology such as scanner data is not as widely available outside the United States. Local customs and geography may make it difficult to interview desired respondents; for example, in some countries, women may not be allowed to talk to strangers.

Country Entry: Decisions and Strategies

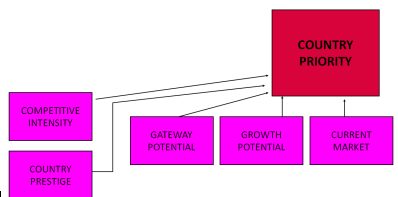

Segmentation, Targeting, and Positioning. Segmentation, in marketing, is usually done at the customer level. However, in international marketing, it may sometimes be useful to see countries as segments. This allows the decision maker to focus on common aspects of countries and avoid information overload. It should be noted that variations within some countries (e.g., Brazil) are very large and therefore, averages may not be meaningful. Country level segmentation may be done on levels such as geography—based on the belief that neighboring countries and countries with a particular type of climate or terrain tend to share similarities, demographics (e.g., population growth, educational attainment, population age distribution), or income. Segmenting on income is tricky since the relative prices between countries may differ significantly (based, in part, on purchasing power parity measures that greatly affect the relative cost of imported and domestically produced products).

The importance of STP. Segmentation is the cornerstone of marketing—almost all marketing efforts in some way relate to decisions on who to serve or how to implement positioning through the different parts of the marketing mix. For example, one’s distribution strategy should consider where one’s target market is most likely to buy the product, and a promotional strategy should consider the target’s media habits and which kinds of messages will be most persuasive. Although it is often tempting, when observing large markets, to try to be “all things to all people,” this is a dangerous strategy because the firm may lose its distinctive appeal to its chosen segments.

In terms of the “big picture,” members of a segment should generally be as similar as possible to each other on a relevant dimension (e.g., preference for quality vs. low price) and as different as possible from members of other segments. That is, members should respond in similar ways to various treatments (such as discounts or high service) so that common campaigns can be aimed at segment members, but in order to justify a different treatment of other segments, their members should have their own unique response behavior.

Approaches to global segmentation. There are two main approaches to global segmentation. At the macro level, countries are seen as segments, given that country aggregate characteristics and statistics tend to differ significantly. For example, there will only be a large market for expensive pharmaceuticals in countries with certain income levels, and entry opportunities into infant clothing will be significantly greater in countries with large and growing birthrates (in countries with smaller birthrates or stable to declining birthrates, entrenched competitors will fight hard to keep the market share).

There are, however, significant differences within countries. For example, although it was thought that the Italian market would demand “no frills” inexpensive washing machines while German consumers would insist on high quality, very reliable ones, it was found that more units of the inexpensive kind were sold in Germany than in Italy—although many German consumers fit the predicted profile, there were large segment differences within that country. At the micro level, where one looks at segments within countries. Two approaches exist, and their use often parallels the firm’s stage of international involvement. Intramarket segmentation involves segmenting each country’s markets from scratch—i.e., an American firm going into the Brazilian market would do research to segment Brazilian consumers without incorporating knowledge of U.S. buyers. In contrast, intermarket segmentation involves the detection of segments that exist across borders. Note that not all segments that exist in one country will exist in another and that the sizes of the segments may differ significantly. For example, there is a huge small car segment in Europe, while it is considerably smaller in the U.S.

Aftermarket segmentation entails several benefits. The fact that products and promotional campaigns may be used across markets introduces economies of scale, and learning that has been acquired in one market may be used in another—e.g., a firm that has been serving a segment of premium quality cellular phone buyers in one country can put its experience to use in another country that features that same segment. (Even though segments may be similar across the cultures, it should be noted that it is still necessary to learn about the local market. For example, although a segment common across two countries may seek the same benefits, the cultures of each country may cause people to respond differently to the “hard sell” advertising that has been successful in one).

The international product life cycle suggests that product adoption and spread in some markets may lag significantly behind those of others. Often, then, a segment that has existed for some time in an “early adopter” country such as the U.S. or Japan will emerge after several years (or even decades) in a “late adopter” country such as Britain or most developing countries. (We will discuss this issue in more detail when we cover the product mix in the second half of the term).

Positioning across markets. Firms often have to make a tradeoff between adapting their products to the unique demands of a country market or gaining benefits of standardization such as cost savings and the maintenance of a consistent global brand image. There are no easy answers here. On the one hand, McDonald’s has spent a great deal of resources to promote its global image; on the other hand, significant accommodations are made to local tastes and preferences—for example, while serving alcohol in U.S. restaurants would go against the family image of the restaurant carefully nurtured over several decades, McDonald’s has accommodated this demand of European patrons.

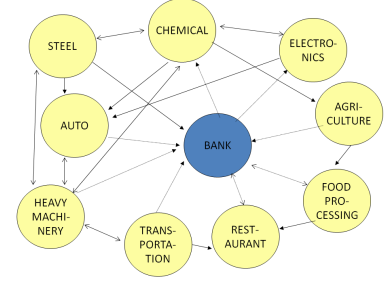

The Japanese Keiretsu Structure. In Japan, many firms are part of a keiretsu, or a conglomerate that ties together businesses that can aid each other. For example, a keiretsu might contain an auto division that buys from a steel division. Both of these might then buy from a iron mining division, which in turns buys from a chemical division that also sells to an agricultural division. The agricultural division then sells to the restaurant division, and an electronics division sells to all others, including the auto division. Since the steel division may not have opportunities for reinvestment, it puts its profits in a bank in the center, which in turns lends it out to the electronics division that is experiencing rapid growth.

This practice insulates the businesses to some extent against the business cycle, guaranteeing an outlet for at least some product in bad times, but this structure has caused problems in Japan as it has failed to “root out” inefficient keiretsu members which have not had to “shape up” to the rigors of the market.

Methods of entry. With rare exceptions, products just don’t emerge in foreign markets overnight—a firm has to build up a market over time. Several strategies, which differ in aggressiveness, risk, and the amount of control that the firm is able to maintain, are available:

- Exporting is a relatively low risk strategy in which few investments are made in the new country. A drawback is that, because the firm makes few if any marketing investments in the new country, market share may be below potential. Further, the firm, by not operating in the country, learns less about the market (What do consumers really want? Which kinds of advertising campaigns are most successful? What are the most effective methods of distribution?) If an importer is willing to do a good job of marketing, this arrangement may represent a “win-win” situation, but it may be more difficult for the firm to enter on its own later if it decides that larger profits can be made within the country.

- Licensing and franchising are also low exposure methods of entry—you allow someone else to use your trademarks and accumulated expertise. Your partner puts up the money and assumes the risk. Problems here involve the fact that you are training a potential competitor and that you have little control over how the business is operated. For example, American fast food restaurants have found that foreign franchisers often fail to maintain American standards of cleanliness. Similarly, a foreign manufacturer may use lower quality ingredients in manufacturing a brand based on premium contents in the home country.

- Contract manufacturing involves having someone else manufacture products while you take on some of the marketing efforts yourself. This saves investment, but again you may be training a competitor.

- Direct entry strategies, where the firm either acquires a firm or builds operations “from scratch” involve the highest exposure, but also the greatest opportunities for profits. The firm gains more knowledge about the local market and maintains greater control, but now has a huge investment. In some countries, the government may expropriate assets without compensation, so direct investment entails an additional risk. A variation involves a joint venture, where a local firm puts up some of the money and knowledge about the local market.

Entry Strategies

Methods of entry. With rare exceptions, products just don’t emerge in foreign markets overnight—a firm has to build up a market over time. Several strategies, which differ in aggressiveness, risk, and the amount of control that the firm is able to maintain, are available:

- Exporting is a relatively low risk strategy in which few investments are made in the new country. A drawback is that, because the firm makes few if any marketing investments in the new country, market share may be below potential. Further, the firm, by not operating in the country, learns less about the market (What do consumers really want? Which kinds of advertising campaigns are most successful? What are the most effective methods of distribution?) If an importer is willing to do a good job of marketing, this arrangement may represent a “win-win” situation, but it may be more difficult for the firm to enter on its own later if it decides that larger profits can be made within the country.

- Licensing and franchising are also low exposure methods of entry—you allow someone else to use your trademarks and accumulated expertise. Your partner puts up the money and assumes the risk. Problems here involve the fact that you are training a potential competitor and that you have little control over how the business is operated. For example, American fast food restaurants have found that foreign franchisers often fail to maintain American standards of cleanliness. Similarly, a foreign manufacturer may use lower quality ingredients in manufacturing a brand based on premium contents in the home country.

- Turnkey Projects. A firm uses knowledge and expertise it has gained in one or more markets to provide a working project—e.g., a factory, building, bridge, or other structure—to a buyer in a new country. The firm can take advantage of investments already made in technology and/or development and may be able to receive greater profits since these investments do not have to be started from scratch again. However, getting the technology to work in a new country may be challenging for a firm that does not have experience with the infrastructure, culture, and legal environment.

- Management Contracts. A firm agrees to manage a facility—e.g., a factory, port, or airport—in a foreign country, using knowledge gained in other markets. Again, one thing is to be able to transfer technology—another is to be able to work in a new country with a different infrastructure, culture, and political/legal environment.

- Contract manufacturing involves having someone else manufacture products while you take on some of the marketing efforts yourself. This saves investment, but again you may be training a competitor.

- Direct entry strategies, where the firm either acquires a firm or builds operations “from scratch” involve the highest exposure, but also the greatest opportunities for profits. The firm gains more knowledge about the local market and maintains greater control, but now has a huge investment. In some countries, the government may expropriate assets without compensation, so direct investment entails an additional risk. A variation involves a joint venture, where a local firm puts up some of the money and knowledge about the local market.

Product Issues in International Marketing

Products and Services. Some marketing scholars and professionals tend to draw a strong distinction between conventional products and services, emphasizing service characteristics such as heterogeneity (variation in standards among providers, frequently even among different locations of the same firm), inseperability from consumption, intangibility, and, in some cases, perishability—the idea that a service cannot generally be created during times of slack and be “stored” for use later. However, almost all products have at least some service component—e.g., a warranty, documentation, and distribution—and this service component is an integral part of the product and its positioning. Thus, it may be more useful to look at the product-service continuum as one between very low and very high levels of tangibility of the service. Income tax preparation, for example, is almost entirely intangible—the client may receive a few printouts, but most of the value is in the service. On the other hand, a customer who picks up rocks for construction from a landowner gets a tangible product with very little value added for service. Firms that offer highly tangible products often seek to add an intangible component to improve perception. Conversely, adding a tangible element to a service—e.g., a binder with information—may address many consumers’ psychological need to get something to show for their money.

On the topic of services, cultural issues may be even more prominent than they are for tangible goods. There are large variations in willingness to pay for quality, and often very large differences in expectations. In some countries, it may be more difficult to entice employees to embrace a firm’s customer service philosophy. Labor regulations in some countries make it difficult to terminate employees whose treatment of customers is substandard. Speed of service is typically important in the U.S. and western countries but personal interaction may seem more important in other countries.

Product Need Satisfaction. We often take for granted the “obvious” need that products seem to fill in our own culture; however, functions served may be very different in others—for example, while cars have a large transportation role in the U.S., they are impractical to drive in Japan, and thus cars there serve more of a role of being a status symbol or providing for individual indulgence. In the U.S., fast food and instant drinks such as Tang are intended for convenience; elsewhere, they may represent more of a treat. Thus, it is important to examine through marketing research consumers’ true motives, desires, and expectations in buying a product.

Approaches to Product Introduction. Firms face a choice of alternatives in marketing their products across markets. An extreme strategy involves customization, whereby the firm introduces a unique product in each country, usually with the belief tastes differ so much between countries that it is necessary more or less to start from “scratch” in creating a product for each market. On the other extreme, standardization involves making one global product in the belief the same product can be sold across markets without significant modification—e.g., Intel microprocessors are the same regardless of the country in which they are sold. Finally, in most cases firms will resort to some kind of adaptation, whereby a common product is modified to some extent when moved between some markets—e.g., in the United States, where fuel is relatively less expensive, many cars have larger engines than their comparable models in Europe and Asia; however, much of the design is similar or identical, so some economies are achieved. Similarly, while Kentucky Fried Chicken serves much the same chicken with the eleven herbs and spices in Japan, a lesser amount of sugar is used in the potato salad, and fries are substituted for mashed potatoes.

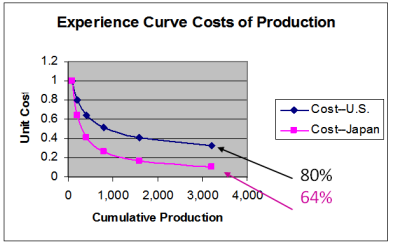

There are certain benefits to standardization. Firms that produce a global product can obtain economies of scale in manufacturing, and higher quantities produced also lead to a faster advancement along the experience curve. Further, it is more feasible to establish a global brand as less confusion will occur when consumers travel across countries and see the same product. On the down side, there may be significant differences in desires between cultures and physical environments—e.g., software sold in the U.S. and Europe will often utter a “beep” to alert the user when a mistake has been made; however, in Asia, where office workers are often seated closely together, this could cause embarrassment.

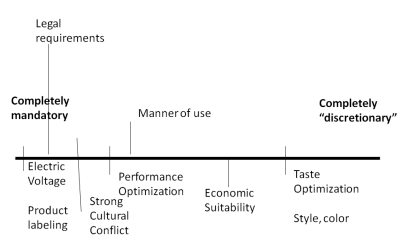

Adaptations come in several forms. Mandatory adaptations involve changes that have to be made before the product can be used—e.g., appliances made for the U.S. and Europe must run on different voltages, and a major problem was experienced in the European Union when hoses for restaurant frying machines could not simultaneously meet the legal requirements of different countries. “Discretionary” changes are changes that do not have to be made before a product can be introduced (e.g., there is nothing to prevent an American firm from introducing an overly sweet soft drink into the Japanese market), although products may face poor sales if such changes are not made. Discretionary changes may also involve cultural adaptations—e.g., in Sesame Street, the Big Bird became the Big Camel in Saudi Arabia.

Another distinction involves physical product vs. communication adaptations. In order for gasoline to be effective in high altitude regions, its octane must be higher, but it can be promoted much the same way. On the other hand, while the same bicycle might be sold in China and the U.S., it might be positioned as a serious means of transportation in the former and as a recreational tool in the latter. In some cases, products may not need to be adapted in either way (e.g., industrial equipment), while in other cases, it might have to be adapted in both (e.g., greeting cards, where the both occasions, language, and motivations for sending differ). Finally, a market may exist abroad for a product which has no analogue at home—e.g., hand-powered washing machines.

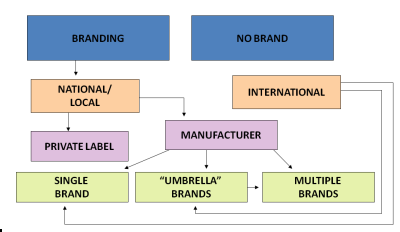

Branding. While Americans seem to be comfortable with category specific brands, this is not the case for Asian consumers. American firms observed that their products would be closely examined by Japanese consumers who could not find a major brand name on the packages, which was required as a sign of quality. Note that Japanese keiretsus span and use their brand name across multiple industries—e.g., Mitsubishi, among other things, sells food, automobiles, electronics, and heavy construction equipment.

The International Product Life Cycle (PLC). Consumers in different countries differ in the speed with which they adopt new products, in part for economic reasons (fewer Malaysian than American consumers can afford to buy VCRs) and in part because of attitudes toward new products (pharmaceuticals upset the power afforded to traditional faith healers, for example). Thus, it may be possible, when one market has been saturated, to continue growth in another market—e.g., while somewhere between one third and one half of American homes now contain a computer, the corresponding figures for even Europe and Japan are much lower and thus, many computer manufacturers see greater growth potential there. Note that expensive capital equipment may also cycle between countries—e.g., airlines in economically developed countries will often buy the newest and most desired aircraft and sell off older ones to their counterparts in developing countries. While in developed countries, “three part” canning machines that solder on the bottom with lead are unacceptable for health reasons, they have found a market in developing countries.

Diffusion of innovation. Good new innovations often do not spread as quickly as one might expect—e.g., although the technology for microwave ovens has existed since the 1950s, they really did not take off in the United States until the late seventies or early eighties, and their penetration is much lower in most other countries. The typewriter, telephone answering machines, and cellular phones also existed for a long time before they were widely adopted.

Certain characteristics of products make them more or less likely to spread. One factor is relative advantage. While a computer offers a huge advantage over a typewriter, for example, the added gain from having an electric typewriter over a manual one was much smaller. Another issue is compatibility, both in the social and physical sense. A major problem with the personal computer was that it could not read the manual files that firms had maintained, and birth control programs are resisted in many countries due to conflicts with religious values. Complexity refers to how difficult a new product is to use—e.g., some people have resisted getting computers because learning to use them takes time. Trialability refers to the extent to which one can examine the merits of a new product without having to commit a huge financial or personal investment—e.g., it is relatively easy to try a restaurant with a new ethnic cuisine, but investing in a global positioning navigation system is riskier since this has to be bought and installed in one’s car before the consumer can determine whether it is worthwhile in practice. Finally, observability refers to the extent to which consumers can readily see others using the product—e.g., people who do not have ATM cards or cellular phones can easily see the convenience that other people experience using them; on the other hand, VCRs are mostly used in people’s homes, and thus only an owner’s close friends would be likely to see it.

At the societal level, several factors influence the spread of an innovation. Not surprisingly, cosmopolitanism, the extent to which a country is connected to other cultures, is useful. Innovations are more likely to spread where there is a higher percentage of women in the work force; these women both have more economic power and are able to see other people use the products and/or discuss them. Modernity refers to the extent to which a culture values “progress.” In the U.S., “new and improved” is considered highly attractive; in more traditional countries, their potential for disruption cause new products to be seen with more skepticism. Although U.S. consumers appear to adopt new products more quickly than those of other countries, we actually score lower on homiphily, the extent to which consumers are relatively similar to each other, and physical distance, where consumers who are more spread out are less likely to interact with other users of the product. Japan, which ranks second only to the U.S., on the other hand, scores very well on these latter two factors.

International Promotion

Promotional tools. Numerous tools can be used to influence consumer purchases:

- Advertising—in or on newspapers, radio, television, billboards, busses, taxis, or the Internet.

- Price promotions—products are being made available temporarily as at a lower price, or some premium (e.g., toothbrush with a package of toothpaste) is being offered for free.

- Sponsorships

- Point-of-purchase—the manufacturer pays for extra display space in the store or puts a coupon right by the product

- Other method of getting the consumer’s attention—all the Gap stores in France may benefit from the prominence of the new store located on the Champs-Elysees

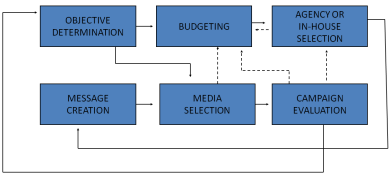

Promotional objectives. Promotional objectives involve the question of what the firm hopes to achieve with a campaign—“increasing profits” is too vague an objective, since this has to be achieved through some intermediate outcome (such as increasing market share, which in turn is achieved by some change in consumers which cause them to buy more). Some common objectives that firms may hold:

- Awareness. Many French consumers do not know that the Gap even exists, so they cannot decide to go shopping there. This objective is often achieved through advertising, but could also be achieved through favorable point-of-purchase displays. Note that since advertising and promotional stimuli are often afforded very little attention by consumers, potential buyers may have to be exposed to the promotional stimulus numerous times before it “registers.”

- Trial. Even when consumers know that a product exists and could possibly satisfy some of their desires, it may take a while before they get around to trying the product—especially when there are so many other products that compete for their attention and wallets. Thus, the next step is often to try get consumer to try the product at least once, with the hope that they will make repeat purchases. Coupons are often an effective way of achieving trial, but these are illegal in some countries and in some others, the infrastructure to readily accept coupons (e.g., clearing houses) does not exist. Continued advertising and point-of-purchase displays may be effective. Although Coca Cola is widely known in China, a large part of the population has not yet tried the product.

- Attitude toward the product. A high percentage of people in the U.S. and Europe has tried Coca Cola, so a more reasonable objective is to get people to believe positive things about the product—e.g., that it has a superior taste and is better than generics or store brands. This is often achieved through advertising.

- Temporary sales increases. For mature products and categories, attitudes may be fairly well established and not subject to cost-effective change. Thus, it may be more useful to work on getting temporary increases in sales (which are likely to go away the incentives are removed). In the U.S. and Japan, for example, fast food restaurants may run temporary price promotions to get people to eat out more or switch from competitors, but when these promotions end, sales are likely to move back down again (in developing countries, in contrast, trial may be a more appropriate objective in this category).

Note that in new or emerging markets, the first objectives are more likely to be useful while, for established products, the latter objectives may be more useful in mature markets such as Japan, the U.S., and Western Europe.

Constraints on Global Communications Strategies. Although firms that seek standardized positions may seek globally unified campaigns, there are several constraints:

- Language barriers: The advertising will have to be translated, not just into the generic language category (e.g., Portuguese) but also into the specific version spoken in the region (e.g., Brazilian Portuguese). (Occasionally, foreign language ads are deliberately run to add mystique to a product, but this is the exception rather than the rule).

- Cultural barriers. Subtle cultural differences may make an ad that tested well in one country unsuitable in another—e.g., an ad that featured a man walking in to join his wife in the bathroom was considered an inappropriate invasion in Japan. Symbolism often differs between cultures, and humor, which is based on the contrast to people’s experiences, tends not to travel well. Values also tend to differ between cultures—in the U.S. and Australia, excelling above the group is often desirable, while in Japan, “The nail that sticks out gets hammered down.” In the U.S., “The early bird gets the worm” while in China “The first bird in the flock gets shot down.”

- Local attitudes toward advertising. People in some countries are more receptive to advertising than others. While advertising is accepted as a fact of life in the U.S., some Europeans find it too crass and commercial.

- Media infrastructure. Cable TV is not well developed in some countries and regions, and not all media in all countries accept advertising. Consumer media habits also differ dramatically; newspapers appear to have a higher reach than television and radio in parts of Latin America.

- Advertising regulations. Countries often have arbitrary rules on what can be advertised and what can be claimed. Comparative advertising is banned almost everywhere outside the U.S. Holland requires that a toothbrush be displayed in advertisements for sweets, and some countries require that advertising to be shown there be produced in the country.

Some cultural dimensions:

- Directness vs. indirectness: U.S. advertising tends to emphasize directly why someone would benefit from buying the product. This, however, is considered too pushy for Japanese consumers, where it is felt to be arrogant of the seller to presume to know what the consumer would like.

- Comparison: Comparative advertising is banned in most countries and would probably be very counterproductive, as an insulting instance of confrontation and bragging, in Asia even if it were allowed. In the U.S., comparison advertising has proven somewhat effective (although its implementation is tricky) as a way to persuade consumers what to buy.

- Humor. Although humor is a relatively universal phenomenon, what is considered funny between countries differs greatly, so pre-testing is essential.

- Gender roles. A study found that women in U.S. advertising tended to be shown in more traditional roles in the U.S. than in Europe or Australia. On the other hand, some countries are even more traditional—e.g., a Japanese ad that claimed a camera to be “so simple that even a woman can use it” was not found to be unusually insulting.

- Explicitness. Europeans tend to allow for considerably more explicit advertisements, often with sexual overtones, than Americans.

- Sophistication. Europeans, particularly the French, demand considerably more sophistication than Americans who may react more favorably to emotional appeals—e.g., an ad showing a mentally retarded young man succeeding in a job at McDonald’s was very favorably received in the U.S. but was booed at the Cannes film festival in France.

- Popular vs. traditional culture. U.S. ads tend to employ contemporary, popular culture, often including current music while those in more traditional cultures tend to refer more to classical culture.

- Information content vs. fluff. American ads contain a great deal of “puffery,” which was found to be very ineffective in Eastern European countries because it resembled communist propaganda too much. The Eastern European consumers instead wanted hard, cold facts.

Advertising standardization. Issues surrounding advertising standardization tend to parallel issues surrounding product and positioning standardization. On the plus side, economies of scale are achieved, a consistent image can be established across markets, creative talent can be utilized across markets, and good ideas can be transplanted from one market to others. On the down side, cultural differences, peculiar country regulations, and differences in product life cycle stages make this approach difficult. Further, local advertising professionals may resist campaigns imposed from the outside—sometimes with good reasons and sometimes merely to preserve their own creative autonomy.

Legal issues. Countries differ in their regulations of advertising, and some products are banned from advertising on certain media (large supermarket chains are not allowed to advertise on TV in France, for example). Other forms of promotion may also be banned or regulated. In some European countries, for example, it is illegal to price discriminate between consumers, and thus coupons are banned and in some, it is illegal to offer products on sale outside a very narrow seasonal and percentage range.

Pricing Issues in International Marketing

Price can best be defined in ratio terms, giving the equation

resources given up

price = ———————————————

goods received

This implies that there are several ways that the price can be changed:

- “Sticker” price changes—the most obvious way to change the price is the price tag— you get the same thing, but for a different (usually larger) amount of money.

- Change quantity. Often, consumers respond unfavorably to an increased sticker price, and changes in quantity are sometimes noticed less—e.g., in the 1970s, the wholesale cost of chocolate increased dramatically, and candy manufacturers responded by making smaller candy bars. Note that, for cash flow reasons, consumers in less affluent countries may need to buy smaller packages at any one time (e.g., forking out the money for a large tube of toothpaste is no big deal for most American families, but it introduces a greater strain on the budget of a family closer to the subsistence level).

- Change quality. Another way candy manufacturers have effectively increased prices is through a reduction in quality. In a candy bar, the “gooey” stuff is much cheaper than chocolate. It is frequently tempting for foreign licensees of a major brand name to use inferior ingredients.

- Change terms. In the old days, most software manufacturers provided free support for their programs—it used to be possible to call the WordPerfect Corporation on an 800 number to get free help. Nowadays, you either have to call a 900 number or have a credit card handy to get help from many software makers. Another way to change terms is to do away with favorable financing terms.

Reference Prices. Consumers often develop internal reference prices, or expectations about what something should cost, based mostly on their experience. Most drivers with long commutes develop a good feeling of what gasoline should cost, and can tell a bargain or a ripoff.

Reference prices are more likely to be more precise for frequently purchased and highly visible products. Therefore, retailers very often promote soft drinks, since consumers tend to have a good idea of prices and these products are quite visible. The trick, then, is to be more expensive on products where price expectations are muddier.

Marketers often try to influence people’s price perceptions through the use of external reference prices—indicators given to the consumer as to how much something should cost. Examples include:

- Manufacturer’s Suggested Retail Price (MSRP). This is often pure fiction. The suggested retail prices in certain categories are deliberately set so high that even full service retailers can sell at a “discount.” Thus, although the consumer may contrast the offering price against the MSRP, this latter figure is quite misleading.

- “SALE! Now $2.99; Regular Price $5.00.” For this strategy to be used legally in most countries, the claim must be true (consistency of enforcement in some countries is, of course, another matter). However, certain products are put on sale so frequently that the “regular” price is meaningless. In the early 1990s, Sears was reported to sell some 55% of its merchandise on sale.

- “WAS $10.00, now $6.99.”

- “Sold elsewhere for $150.00; our price: $99.99.”

Reference prices have significant international implications. While marketers may choose to introduce a product at a low price in order to induce trial, which is useful in a new market where the penetration of a product is low, this may have serious repercussions as consumers may develop a low reference price and may thus resist paying higher prices in the future.

Selected International Pricing Issues. In some cultures, particularly where retail stores are smaller and the buyer has the opportunity to interact with the owner, bargaining may be more common, and it may thus be more difficult for the manufacturer to influence retail level pricing.

Two phenomena may occur when products are sold in disparate markets. When a product is exported, price escalation, whereby the product dramatically increases in price in the export market, is likely to take place. This usually occurs because a longer distribution chain is necessary and because smaller quantities sold through this route will usually not allow for economies of scale. “Gray” markets occur when products are diverted from one market in which they are cheaper to another one where prices are higher—e.g., Luis Vuitton bags were significantly more expensive in Japan than in France, since the profit maximizing price in Japan was higher and thus bags would be bought in France and shipped to Japan for resale. The manufacturer therefore imposed quantity limits on buyers. Since these quantity limits were circumvented by enterprising exchange students who were recruited to buy their quota on a daily basis, prices eventually had to be lowered in Japan to make the practice of diversion unattractive. Where the local government imposes price controls, a firm may find the market profitable to enter nevertheless since revenues from the new market only have to cover marginal costs. However, products may then be attractive to divert to countries without such controls.

Transfer pricing involves what one subsidiary will charge another for products or components supplied for use in another country. Firms will often try to charge high prices to subsidiaries in countries with high taxes so that the income earned there will be minimized.

Antitrust laws are relevant in pricing decisions, and anti-dumping regulations are especially noteworthy. In general, it is illegal to sell a product below your cost of production, which may make a penetration pricing entry strategy infeasible. Japan has actively lobbied the World Trade Organization (WTO) to relax its regulations, which generally require firms to price no lower than their average fully absorbed cost (which incorporates both variable and fixed costs).

Alternatives to “hard” currency deals. Buyers in some countries do not have ready access to convertible currency, and governments will often try limit firms’ ability to spend money abroad. Thus, some firms have been forced into non-cash deals. In barter, the seller takes payment in some product produced in the buying country—e.g., Lockheed (back when it was an independent firm) took Spanish wine in return for aircraft, and sellers to Eastern Europe have taken their payment in ham. An offset contract is somewhat more flexible in that the buyer can get paid but instead has to buy, or cause others to buy, products for a certain value within a specified period of time.

Psychological issues: Most pricing research has been done on North Americans, and this raises serious problems of generalizability. Americans are used to sales, for example, while consumers in countries where goods are more scarce may attribute a sale to low quality rather than a desire to gain market share. There is some evidence that perceived price quality relationships are quite high in Britain and Japan (thus, discount stores have had difficulty there), while in developing countries, there is less trust in the market. Cultural differences may influence the extent of effort put into evaluating deals (potentially impacting the effectiveness of odd-even pricing and promotion signaling). The fact that consumers in some economies are usually paid weekly, as opposed to biweekly or monthly, may influence the effectiveness of framing attempts—”a dollar a day” is a much bigger chunk from a weekly than a monthly paycheck.

International Distribution

Promotional tools. Numerous tools can be used to influence consumer purchases:

- Advertising—in or on newspapers, radio, television, billboards, busses, taxis, or the Internet.

- Price promotions—products are being made available temporarily as at a lower price, or some premium (e.g., toothbrush with a package of toothpaste) is being offered for free.

- Sponsorships

- Point-of-purchase—the manufacturer pays for extra display space in the store or puts a coupon right by the product

- Other method of getting the consumer’s attention—all the Gap stores in France may benefit from the prominence of the new store located on the Champs-Elysees.

Promotional objectives. Promotional objectives involve the question of what the firm hopes to achieve with a campaign—“increasing profits” is too vague an objective, since this has to be achieved through some intermediate outcome (such as increasing market share, which in turn is achieved by some change in consumers which cause them to buy more). Some common objectives that firms may hold:

- Awareness. Many French consumers do not know that the Gap even exists, so they cannot decide to go shopping there. This objective is often achieved through advertising, but could also be achieved through favorable point-of-purchase displays. Note that since advertising and promotional stimuli are often afforded very little attention by consumers, potential buyers may have to be exposed to the promotional stimulus numerous times before it “registers.”

- Trial. Even when consumers know that a product exists and could possibly satisfy some of their desires, it may take a while before they get around to trying the product—especially when there are so many other products that compete for their attention and wallets. Thus, the next step is often to try get consumer to try the product at least once, with the hope that they will make repeat purchases. Coupons are often an effective way of achieving trial, but these are illegal in some countries and in some others, the infrastructure to readily accept coupons (e.g., clearing houses) does not exist. Continued advertising and point-of-purchase displays may be effective. Although Coca Cola is widely known in China, a large part of the population has not yet tried the product.

- Attitude toward the product. A high percentage of people in the U.S. and Europe has tried Coca Cola, so a more reasonable objective is to get people to believe positive things about the product—e.g., that it has a superior taste and is better than generics or store brands. This is often achieved through advertising.

- Temporary sales increases. For mature products and categories, attitudes may be fairly well established and not subject to cost-effective change. Thus, it may be more useful to work on getting temporary increases in sales (which are likely to go away the incentives are removed). In the U.S. and Japan, for example, fast food restaurants may run temporary price promotions to get people to eat out more or switch from competitors, but when these promotions end, sales are likely to move back down again (in developing countries, in contrast, trial may be a more appropriate objective in this category).

Note that in new or emerging markets, the first objectives are more likely to be useful while, for established products, the latter objectives may be more useful in mature markets such as Japan, the U.S., and Western Europe.

Constraints on Global Communications Strategies. Although firms that seek standardized positions may seek globally unified campaigns, there are several constraints:

- Language barriers: The advertising will have to be translated, not just into the generic language category (e.g., Portuguese) but also into the specific version spoken in the region (e.g., Brazilian Portuguese). (Occasionally, foreign language ads are deliberately run to add mystique to a product, but this is the exception rather than the rule).

- Cultural barriers. Subtle cultural differences may make an ad that tested well in one country unsuitable in another—e.g., an ad that featured a man walking in to join his wife in the bathroom was considered an inappropriate invasion in Japan. Symbolism often differs between cultures, and humor, which is based on the contrast to people’s experiences, tends not to travel well. Values also tend to differ between cultures—in the U.S. and Australia, excelling above the group is often desirable, while in Japan, “The nail that sticks out gets hammered down.” In the U.S., “The early bird gets the worm” while in China “The first bird in the flock gets shot down.”

- Local attitudes toward advertising. People in some countries are more receptive to advertising than others. While advertising is accepted as a fact of life in the U.S., some Europeans find it too crass and commercial.

- Media infrastructure. Cable TV is not well developed in some countries and regions, and not all media in all countries accept advertising. Consumer media habits also differ dramatically; newspapers appear to have a higher reach than television and radio in parts of Latin America.

- Advertising regulations. Countries often have arbitrary rules on what can be advertised and what can be claimed. Comparative advertising is banned almost everywhere outside the U.S. Holland requires that a toothbrush be displayed in advertisements for sweets, and some countries require that advertising to be shown there be produced in the country.

Some cultural dimensions:

- Directness vs. indirectness: U.S. advertising tends to emphasize directly why someone would benefit from buying the product. This, however, is considered too pushy for Japanese consumers, where it is felt to be arrogant of the seller to presume to know what the consumer would like.

- Comparison: Comparative advertising is banned in most countries and would probably be very counterproductive, as an insulting instance of confrontation and bragging, in Asia even if it were allowed. In the U.S., comparison advertising has proven somewhat effective (although its implementation is tricky) as a way to persuade consumers what to buy.

- Humor. Although humor is a relatively universal phenomenon, what is considered funny between countries differs greatly, so pre-testing is essential.

- Gender roles. A study found that women in U.S. advertising tended to be shown in more traditional roles in the U.S. than in Europe or Australia. On the other hand, some countries are even more traditional—e.g., a Japanese ad that claimed a camera to be “so simple that even a woman can use it” was not found to be unusually insulting.

- Explicitness. Europeans tend to allow for considerably more explicit advertisements, often with sexual overtones, than Americans.

- Sophistication. Europeans, particularly the French, demand considerably more sophistication than Americans who may react more favorably to emotional appeals—e.g., an ad showing a mentally retarded young man succeeding in a job at McDonald’s was very favorably received in the U.S. but was booed at the Cannes film festival in France.

- Popular vs. traditional culture. U.S. ads tend to employ contemporary, popular culture, often including current music while those in more traditional cultures tend to refer more to classical culture.