It is not uncommon to predict that economic growth in the twenty-first century will be slower than previously thought. While technological advances have the potential to stimulate economic growth, they may not always result in significant increases in productivity or GDP. The low-hanging fruits of innovation may have already been harvested, making future breakthroughs more difficult to achieve.

According to new research, the global economy will grow slower in the twenty-first century than economists predicted a finding that has implications for our ability to adapt to climate change in the coming decades.

A new study that forecasts the economic futures of four income groups of countries over the next century finds that growth will be slower than expected, with developing countries taking longer to close the wealth gap and reach the income levels of wealthier nations. According to a new study published today in Communications Earth & Environment, what economists consider to be the worst-case scenario for global economic growth may actually be the best-case scenario.

According to the study’s authors, the findings indicate that governments should begin planning for slower growth, and that wealthier countries may need to assist lower-income countries in financing climate change adaptations in the coming decades.

We’re at a point where we maybe need to significantly increase financing for [climate] adaptation in developing countries, and we’re also at a point where we might be overestimating our future ability to provide that financing under the current fiscal paradigm.

Matt Burgess

“We’re at a point where we maybe need to significantly increase financing for [climate] adaptation in developing countries, and we’re also at a point where we might be overestimating our future ability to provide that financing under the current fiscal paradigm,” said Matt Burgess, a CIRES fellow, director of the Center for Social and Environmental Futures, and assistant professor of environmental studies at CU Boulder who led the new study.

“We can now start to winnow down the range of possibilities and move forward in more tangible ways,” said Ryan Langendorf, co-author of the new study and a postdoctoral scholar at CU Boulder.

Birth rates are declining and populations are aging in many developed and developing countries. An aging workforce can reduce labor force participation and productivity, weighing on economic growth. The twenty-first century is marked by heightened awareness of environmental issues and resource scarcity. Stricter regulations to combat climate change, for example, could have an impact on traditional industries, potentially slowing economic growth.

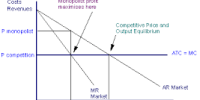

In the new study, Burgess and his colleagues used two economic models to project how much the global economy will grow over the next century and how quickly developing countries will approach the income levels of wealthier nations.

Both models found the global economy will continue to grow, but that growth will be slower than most economists expected and there will be a larger income gap between wealthier and poorer nations. This means richer countries may need to help finance climate adaptations for poorer countries, and debt-ceiling crises, like what the United States experienced this spring, may become more common.

“Slower growth than we think means higher deficits than we expect, all else being equal,” Burgess explained. “That means debt will likely become more contentious and important over time, potentially leading to more debt-ceiling fights.”

According to the researchers, wealthy countries should focus on getting their own financial houses in order before assisting lower-income countries in financing climate adaptations, similar to how people would put on their own oxygen masks during a flight emergency.

“We’re talking about relatively less growth, relatively more inequality, but we’re still talking about a world that is richer than today and more equal across countries than today’s world,” Burgess said.

Nonetheless, many wealthy countries are accustomed to growing their way out of debt, but this may no longer be possible under the new scenario, according to Ashley Dancer, a graduate student at CU Boulder and co-author of the study.

“The next question is, what are some ways that we should or could be assisting [lower-income countries] in adapting, if the expectation is that they will not achieve the level of wealth that would allow them to do so quickly and aggressively?” Dancer stated.