A massive paleogenetic study reveals information about migration patterns, agricultural expansion, and language development from the Caucasus to Western Asia and Southern Europe from the early Copper Age to the late Middle Ages.

In a trio of papers published simultaneously in the journal Science, Ron Pinhasi from the Department of Evolutionary Anthropology and Human Evolution and Archaeological Sciences (HEAS) at the University of Vienna, Songül Alpaslan-Roodenberg from the University of Vienna and Harvard University, Iosif Lazaridis and David Reich at Harvard University, and 202 co-authors report a massive effort of genome-wide sequencing from 727 distinct ancient individuals w They present a systematic picture of the interconnected histories of peoples across the Southern Arc Region, from the dawn of agriculture to late medieval times.

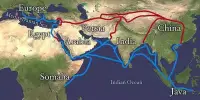

The first paper by the international team looked at the origins and spread of Anatolian and Indo-European languages. The genetic evidence suggests that the Indo-Anatolian language family originated in West Asia, with only secondary dispersals of non-Anatolian Indo-Europeans from the Eurasian steppe. People with Caucasus ancestry moved west into Anatolia and north into the steppe during the first stage, approximately 7,000-5,000 years ago. Some of these people may have spoken Anatolian and Indo-European dialects.

These findings are particularly surprising given that, in a 2019 Science paper co-authored by me on the genetic ancestry of individuals from Ancient Rome, we discovered a cosmopolitan pattern that we thought was unique to Rome.

Ron Pinhasi

All spoken Indo-European languages (e.g., Greek, Armenian and Sanskrit) can be traced back to Yamnaya steppe herders, with Caucasus hunter-gatherer and Eastern hunter-gatherer ancestry, who ~5,000 years ago initiated a chain of migrations across Eurasia. Their southern expansions into the Balkans and Greece and east across the Caucasus into Armenia left a trace in the DNA of the Bronze Age people of the region.

The descendants of the Yamnaya herders admixed differently with the local populations as they spread. The emergence of Greek, Paleo-Balkan, and Albanian (Indo-European) languages in Southeastern Europe, as well as the Armenian language in West Asia, can be traced back to Indo-European speaking migrants from the steppe interacting with local people, as evidenced by various forms of genetic evidence. In Southeastern Europe, the Yamnaya influence was profound, and people with nearly complete Yamnaya ancestry arrived shortly after the start of the Yamnaya migrations.

Some of the most striking findings come from Anatolia, the core region of the Southern Arc, where large-scale data paints a rich picture of change and lack of change over time. The findings show that, in contrast to the Balkans and the Caucasus, the Yamnaya migrations had little impact on Anatolia. Because Anatolian languages (e.g., Hittite, Luwian) lack Eastern hunter-gatherer ancestry, no link to the steppe can be established, in contrast to all other regions where Indo-European languages were spoken.

In contrast to Anatolia’s surprising impermeability to steppe migrations, the southern Caucasus was affected multiple times including prior to the Yamnaya migrations. “I did not expect to find out that the Areni 1 Chalcolithic individuals, who were recovered 15 years ago in the excavation I co-led, would derive ancestry from gene flow from the north to parts of the southern Caucasus more than 1,000 years prior to the expansion of the Yamnaya, and that this northern influence would disappear in the region before reappearing a couple of millennia later. This shows that there is a lot more to be discovered through new excavations and fieldwork in the eastern parts of Western Asia” says Ron Pinhasi.

First farming societies and their interactions

The second paper seeks to understand how the world’s earliest Neolithic populations (~12,000 years ago) were formed. “The genetic results lend support to a scenario of a web of pan-regional contacts between early farming communities. They also provide new evidence that the Neolithic transition was a complex process that did not occur just in one core region, but across Anatolia and the Near East” says Ron Pinhasi.

It presents the first ancient DNA data for Pre-Pottery Neolithic farmers from the Tigris side of northern Mesopotamia — both in eastern Turkey and in northern Iraq — a prime region of the origins of agriculture. It also presents the first ancient DNA from Pre-Pottery farmers from the island of Cyprus, which witnessed the earliest maritime expansion of farmers from the eastern Mediterranean. It furthermore provides new data for early Neolithic farmers from the Northwest Zagros, along with the first data from Neolithic Armenia.

By filling these gaps, the authors were able to study the genetic history of these societies, for which archaeological research documented complex economic and cultural interactions but was unable to trace mating systems and interactions that left no visible material traces. The results show admixture of pre-Neolithic sources related to Anatolian, Caucasus, and Levantine hunter-gatherers, and that these early farming cultures formed an ancestry continuum mirroring West Asia’s geography. The findings also show at least two pulses of migration from the Fertile Crescent heartland to Anatolia’s early farmers.

The Historic Period

The third paper shows how ancient Mediterranean polities preserved ancestry contrasts but were linked by migration since the Bronze Age. The results show that in both the mean and pattern of variation, the ancestry of people who lived around Rome during the Imperial period was nearly identical to that of Roman/Byzantine individuals from Anatolia, whereas Italians prior to the Imperial period had a very different distribution. This suggests that the Roman Empire had a diverse but similar population drawn to a large extent from Anatolian pre-Imperial sources in both its shorter-lived western and longer-lived eastern parts centered on Anatolia.

“These findings are particularly surprising given that, in a 2019 Science paper co-authored by me on the genetic ancestry of individuals from Ancient Rome, we discovered a cosmopolitan pattern that we thought was unique to Rome. Now we can see that other parts of the Roman Empire were just as cosmopolitan as Rome itself” Ron Pinhasi says.