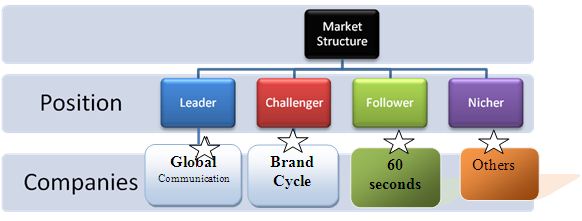

- Market:

-A public place where buyers and sellers make transactions, directly or via intermediaries. Also sometimes means the stock market.

-An actual or nominal place where forces of demand and supply operate, and where buyers and sellers interact (directly or through intermediaries) to trade goods, services, or contracts or instruments, for money or barter.

Markets include mechanisms or means for (1) determining price of the traded item, (2) communicating the price information, (3) facilitating deals and transactions, and (4) effecting distribution. The market for a particular item is made up of existing and potential customers who need it and have the ability and willingness to pay for it.

- Market Characteristics

An industry or market can be analyzed for its attractiveness to a particular company or organization on a number of different characteristics. The list below presents some of the more significant market characteristics that should be considered.

Current market size

Projected market growth rate

Number of competitors, level of fragmentation

Intensity of competition

Technological skills required

Production/operations skills required

Capital requirements

Other barriers to entry

Seasonal and cyclical factors

Industry profitability and returns

Social, political, regulatory and environmental factors

Strategic fits with other businesses already owned

- Types of market

In economics, market types (also known as the number of firms producing identical products).

- Monopolistic competition also called competitive market, where there are a large number of firms, each having a small proportion of the market share and slightly differentiated products.

- Oligopoly, in which a market is dominated by a small number of firms that together control the majority of the market share.

- Duopoly, a special case of an oligopoly with two firms.

- Monopoly, where there is only one provider of a product or service.

- Natural monopoly, a monopoly in which economies of scale cause efficiency to increase continuously with the size of the firm. A firm is a natural monopoly if it is able to serve the entire market demand at a lower cost than any combination of two or more smaller, more specialized firms.

- Perfect competition is a theoretical market structure that features unlimited contestability (or no barriers to entry), an unlimited number of producers and consumers, and a perfectly elastic demand curve.

The imperfectly competitive structure is quite identical to the realistic market conditions where some monopolistic competitors, monopolists, oligopolies, and duopolies exist and dominate the market conditions. The elements of Market Structure include the number and size distribution of firms, entry conditions, and the extent of differentiation.

These somewhat abstract concerns tend to determine some but not all details of a specific concrete market system where buyers and sellers actually meet and commit to trade. Competition is useful because it reveals actual customer demand and induces the seller (operator) to provide service quality levels and price levels that buyers (customers) want, typically subject to the seller’s financial need to cover its costs. In other words, competition can align the seller’s interests with the buyer’s interests and can cause the seller to reveal his true costs and other private information. In the absence of perfect competition, three basic approaches can be adopted to deal with problems related to the control of market power and an asymmetry between the government and the operator with respect to objectives and information: (a) subjecting the operator to competitive pressures, (b) gathering information on the operator and the market, and (c) applying incentive regulation.

| Quick Reference to Basic Market Structures | ||||

| Market Structure | Seller Entry Barriers | Seller Number | Buyer Entry Barriers | Buyer Number |

| Perfect Competition | No | Many | No | Many |

| Monopolistic competition | No | Many | No | Many |

| Oligopoly | Yes | Few | No | Many |

| Oligopsony | No | Many | Yes | Few |

| Monopoly | Yes | One | No | Many |

| Monopsony | No | Many | Yes | One |

The correct sequence of the market structure from most to least competitive is perfect competition, imperfect competition, oligopoly, and pure monopoly.

The main criteria by which one can distinguish between different market structures are: the number and size of producers and consumers in the market, the type of goods and services being traded, and the degree to which information can flow freely.

3.1. Monopolistic competition

Monopolistic competition is a type of imperfect competition such that competing producers sell products that are differentiated from one another as good but not perfect substitutes (such as from branding, quality, or location). In monopolistic competition, a firm takes the prices charged by its rivals as given and ignores the impact of its own prices on the prices of other firms.

In a monopolistically competitive market, firms can behave like monopolies in the short run, including by using market power to generate profit. In the long run, however, other firms enter the market and the benefits of differentiation decrease with competition; the market becomes more like a perfectly competitive one where firms cannot gain economic profit. In practice, however, if consumer rationality/innovativeness is low and heuristics are preferred, monopolistic competition can fall into natural monopoly, even in the complete absence of government intervention. In the presence of coercive government, monopolistic competition will fall into government-granted monopoly. Unlike perfect competition, the firm maintains spare capacity. Models of monopolistic competition are often used to model industries. Textbook examples of industries with market structures similar to monopolistic competition include restaurants, cereal, clothing, shoes, and service industries in large cities. The “founding father” of the theory of monopolistic competition is Edward Hastings Chamberlin, who wrote a pioneering book on the subject, Theory of Monopolistic Competition (1933). Joan Robinson published a book The Economics of Imperfect Competition with a comparable theme of distinguishing perfect from imperfect competition.

Monopolistically competitive markets have the following characteristics:

- There are many producers and many consumers in the market, and no business has total control over the market price.

- Consumers perceive that there are non-price differences among the competitors’ products.

- There are few barriers to entry and exit.

- Producers have a degree of control over price.

The long-run characteristics of a monopolistically competitive market are almost the same as a perfectly competitive market. Two differences between the two are that monopolistic competition produces heterogeneous products and that monopolistic competition involves a great deal of non-price competition, which is based on subtle product differentiation. A firm making profits in the short run will nonetheless only break even in the long run because demand will decrease and average total cost will increase. This means in the long run, a monopolistically competitive firm will make zero economic profit. This illustrates the amount of influence the firm has over the market; because of brand loyalty, it can raise its prices without losing all of its customers. This means that an individual firm’s demand curve is downward sloping, in contrast to perfect competition, which has a perfectly elastic demand schedule.

A. Major characteristics

There are six characteristics of monopolistic competition (MC):

- Product differentiation

- Many firms

- Free entry and exit in the long run

- Independent decision making

- Market Power

- Buyers and Sellers have perfect information

Product differentiation:

MC firms sell products that have real or perceived non-price differences. However, the differences are not so great as to eliminate other goods as substitutes. Technically, the cross price elasticity of demand between goods in such a market is positive. In fact, the XED would be high. MC goods are best described as close but imperfect substitutes. The goods perform the same basic functions but have differences in qualities such as type, style, quality, reputation, appearance, and location that tend to distinguish them from each other. For example, the basic function of motor vehicles is basically the same – to move people and objects from point A to B in reasonable comfort and safety. Yet there are many different types of motor vehicles such as motor scooters, motor cycles, trucks, cars and SUVs and many variations even within these categories.

Many firms:

There are many firms in each MC product group and many firms on the side lines prepared to enter the market. A product group is a “collection of similar products”. The fact that there are “many firms” gives each MC firm the freedom to set prices without engaging in strategic decision making regarding the prices of other firms and each firm’s actions have a negligible impact on the market. For example, a firm could cut prices and increase sales without fear that its actions will prompt retaliatory responses from competitors.

How many firms will an MC market structure support at market equilibrium? The answer depends on factors such as fixed costs, economies of scale and the degree of product differentiation. For example, the higher the fixed costs, the fewer firms the market will support. Also the greater the degree of product differentiation – the more the firm can separate itself from the pack – the fewer firms there will be at market equilibrium.

Free entry and exit:

In the long run there is free entry and exit. There are numerous firms waiting to enter the market each with its own “unique” product or in pursuit of positive profits and any firm unable to cover its costs can leave the market without incurring liquidation costs. This assumption implies that there are low start up costs, no sunk costs and no exit costs. The cost of entering and exit is very low.

Independent decision making:

Each MC firm independently sets the terms of exchange for its product. The firm gives no consideration to what effect its decision may have on competitors. The theory is that any action will have such a negligible effect on the overall market demand that an MC firm can act without fear of prompting heightened competition. In other words each firm feels free to set prices as if it were a monopoly rather than an oligopoly.

Market power:

MC firms have some degree of market power. Market power means that the firm has control over the terms and conditions of exchange. An MC firm can raise it prices without losing all its customers. The firm can also lower prices without triggering a potentially ruinous price war with competitors. The source of an MC firm’s market power is not barriers to entry since they are low. Rather, an MC firm has market power because it has relatively few competitors, those competitors do not engage in strategic decision making and the firms sell differentiated product. Market power also means that an MC firm faces a downward sloping demand curve. The demand curve is highly elastic although not “flat”.

Imperfect information:

No sellers or buyers have complete market information, like market demand or market supply.

| Market Structure comparison | ||||||||

| Number of firms | Market power | Elasticity of demand | Product differentiation | Excess profits | Efficiency | Profit maximization condition | Pricing power | |

| Perfect Competition | Infinite | None | Perfectly elastic | None | No | Yes | P=MR=MC | Price taker |

| Monopolistic competition | Many | Low | Highly elastic (long run) | High | Yes/No (Short/Long) | No | MR=MC | Price setter |

| Monopoly | One | High | Relatively inelastic | Absolute (across industries) | Yes | No | MR=MC | Price setter |

Inefficiency:

There are two sources of inefficiency in the MC market structure. First, at its optimum output the firm charges a price that exceeds marginal costs, The MC firm maximizes profits where MR = MC. Since the MC firm’s demand curve is downward sloping this means that the firm will be charging a price that exceeds marginal costs. The monopoly power possessed by an MC firm means that at its profit maximizing level of production there will be a net loss of consumer (and producer) surplus. The second source of inefficiency is the fact that MC firms operate with excess capacity. That is, the MC firm’s profit maximizing output is less than the output associated with minimum average cost. Both a PC and MC firm will operate at a point where demand or price equals average cost. For a PC firm this equilibrium condition occurs where the perfectly elastic demand curve equals minimum average cost. A MC firm’s demand curve is not flat but is downward sloping. Thus in the long run the demand curve will be tangent to the long run average cost curve at a point to the left of its minimum. The result is excess capacity.

Problems:

While monopolistically competitive firms are inefficient, it is usually the case that the costs of regulating prices for every product that is sold in monopolistic competition far exceed the benefits of such regulation. The government would have to regulate all firms that sold heterogeneous products—an impossible proposition in a market economy. A monopolistically competitive firm might be said to be marginally inefficient because the firm produces at an output where average total cost is not a minimum. A monopolistically competitive market might be said to be a marginally inefficient market structure because marginal cost is less than price in the long run.

Another concern of critics of monopolistic competition is that it fosters advertising and the creation of brand names. Critics argue that advertising induces customers into spending more on products because of the name associated with them rather than because of rational factors. Defenders of advertising dispute this, arguing that brand names can represent a guarantee of quality and that advertising helps reduce the cost to consumers of weighing the tradeoffs of numerous competing brands. There are unique information and information processing costs associated with selecting a brand in a monopolistically competitive environment. In a monopoly market, the consumer is faced with a single brand, making information gathering relatively inexpensive. In a perfectly competitive industry, the consumer is faced with many brands, but because the brands are virtually identical information gathering is also relatively inexpensive. In a monopolistically competitive market, the consumer must collect and process information on a large number of different brands to be able to select the best of them. In many cases, the cost of gathering information necessary to selecting the best brand can exceed the benefit of consuming the best brand instead of a randomly selected brand.

Evidence suggests that consumers use information obtained from advertising not only to assess the single brand advertised, but also to infer the possible existence of brands that the consumer has, heretofore, not observed, as well as to infer consumer satisfaction with brands similar to the advertised brand.

B. Examples:

In many U.S. markets, producers practice product differentiation by altering the physical composition of products, using special packaging, or simply claiming to have superior products based on brand images or advertising. Toothpastes, toilet papers, computer software and operating systems are examples of differentiated products.

3.2. Oligopoly:

Oligopoly is a common market form. As a quantitative description of oligopoly, the four-firm concentration ratio is often utilized. This measure expresses the market share of the four largest firms in an industry as a percentage. For example, as of fourth quarter 2008, Verizon, AT&T, Sprint, Nextel, and T-Mobile together control 89% of the US cellular phone market.

Oligopolistic competition can give rise to a wide range of different outcomes. In some situations, the firms may employ restrictive trade practices (collusion, market sharing etc.) to raise prices and restrict production in much the same way as a monopoly. Where there is a formal agreement for such collusion, this is known as a cartel. A primary example of such a cartel is OPEC which has a profound influence on the international price of oil.

Firms often collude in an attempt to stabilize unstable markets, so as to reduce the risks inherent in these markets for investment and product development. There are legal restrictions on such collusion in most countries. There does not have to be a formal agreement for collusion to take place (although for the act to be illegal there must be actual communication between companies)–for example, in some industries there may be an acknowledged market leader which informally sets prices to which other producers respond, known as price leadership.

In other situations, competition between sellers in an oligopoly can be fierce, with relatively low prices and high production. This could lead to an efficient outcome approaching perfect competition. The competition in an oligopoly can be greater than when there are more firms in an industry if, for example, the firms were only regionally based and did not compete directly with each other.

Thus the welfare analysis of oligopolies is sensitive to the parameter values used to define the market’s structure. In particular, the level of dead weight loss is hard to measure. The study of product differentiation indicates that oligopolies might also create excessive levels of differentiation in order to stifle competition.

Oligopoly theory makes heavy use of game theory to model the behavior of oligopolies:

- Stackelberg’s duopoly. In this model the firms move sequentially (see Stackelberg competition).

- Cournot’s duopoly. In this model the firms simultaneously choose quantities (see Cournot competition).

- Bertrand’s oligopoly. In this model the firms simultaneously choose prices (see Bertrand competition).

A. Characteristics:

Profit maximization conditions: An oligopoly maximizes profits by producing where marginal revenue equals marginal costs.

Ability to set price: Oligopolies are price setters rather than price takers.

Entry and exit: Barriers to entry are high. The most important barriers are economies of scale, patents, access to expensive and complex technology, and strategic actions by incumbent firms designed to discourage or destroy nascent firms. Additional sources of barriers to entry often result from government regulation favoring existing firms making it difficult for new firms to enter the market.

Number of firms: “Few” – a “handful” of sellers. There are so few firms that the actions of one firm can influence the actions of the other firms.

Long run profits: Oligopolies can retain long run abnormal profits. High barriers of entry prevent sideline firms from entering market to capture excess profits.

Product differentiation: Product may be homogeneous (steel) or differentiated (automobiles).

Perfect knowledge: Assumptions about perfect knowledge vary but the knowledge of various economic actors can be generally described as selective. Oligopolies have perfect knowledge of their own cost and demand functions but their inter-firm information may be incomplete. Buyers have only imperfect knowledge as to price, cost and product quality.

Interdependence: The distinctive feature of an oligopoly is interdependence. Oligopolies are typically composed of a few large firms. Each firm is so large that its actions affect market conditions. Therefore the competing firms will be aware of a firm’s market actions and will respond appropriately. This means that in contemplating a market action, a firm must take into consideration the possible reactions of all competing firms and the firm’s countermoves. It is very much like a game of chess or pool in which a player must anticipate a whole sequence of moves and countermoves in determining how to achieve his objectives. For example, an oligopoly considering a price reduction may wish to estimate the likelihood that competing firms would also lower their prices and possibly trigger a ruinous price war. Or if the firm is considering a price increase, it may want to know whether other firms will also increase prices or hold existing prices constant. This high degree of interdependence and need to be aware of what the other guy is doing or might do is to be contrasted with lack of interdependence in other market structures. In a PC market there is zero interdependence because no firm is large enough to affect market price. All firms in a PC market are price takers, information which they robotically follow in maximizing profits. In a monopoly there are no competitors to be concerned about. In a monopolistically competitive market each firm’s effects on market conditions is so negligible as to be safely ignored by competitors.

B. Examples

In industrialized economies, barriers to entry have resulted in oligopolies forming in many sectors, with unprecedented levels of competition fueled by increasing globalization. Market shares in an oligopoly are typically determined by product development and advertising. For example, there are now only a small number of manufacturers of civil passenger aircraft, though Brazil (Embraer) and Canada (Bombardier) have participated in the small passenger aircraft market sector. Oligopolies have also arisen in heavily-regulated markets such as wireless communications: in some areas only two or three providers are licensed to operate.

3.3. Duopoly

A true duopoly is a specific type of oligopoly where only two producers exist in one market. In reality, this definition is generally used where only two firms have dominant control over a market. In the field of industrial organization, it is the most commonly studied form of oligopoly due to its simplicity.

Duopoly models in economics

There are two principal duopoly models, Cournot duopoly and Bertrand duopoly:

- The Cournot model, which shows that two firms assume each other’s output and treats this as a fixed amount, and produce in their own firm according to this.

- The Bertrand model, in which, in a game of two firms, each one of them will assume that the other will not change prices in response to its price cuts. When both firms use this logic, they will reach Nash equilibrium.

Examples

The most commonly cited duopoly is that between Visa and MasterCard, who between them control a large proportion of the electronic payment processing market. In 2000 they were the defendants in a US Department of Justice antitrust lawsuit. An appeal was upheld in 2004.

3.4. Monopoly

A monopoly exists when a specific person or enterprise is the only supplier of a particular commodity. Monopolies are thus characterized by a lack of economic competition to produce the good or service and a lack of viable substitute goods. The verb “monopolies” refers to the process by which a company gains much greater market share than what is expected with perfect competition.

A monopoly is distinguished from a monopsony, in which there is only one buyer of a product or service; a monopoly may also have monopsony control of a sector of a market. Likewise, a monopoly should be distinguished from a cartel (a form of oligopoly), in which several providers act together to coordinate services, prices or sale of goods. Monopolies, monopolies and oligopolies are all situations such that one or a few of the entities have market power and therefore interact with their customers (monopoly), suppliers (monopsony) and the other companies (oligopoly) in a game theoretic manner – meaning that expectations about their behavior affects other players’ choice of strategy and vice versa. This is to be contrasted with the model of perfect competition in which companies are “price takers” and do not have market power.

When not coerced legally to do otherwise, monopolies typically maximize their profit by producing fewer goods and selling them at higher prices than would be the case for perfect competition. (See also Bertrand, Cournot or Stackelberg equilibrium, market power, market share, market concentration, Monopoly profit, and industrial economics). Sometimes governments decide legally that a given company is a monopoly that doesn’t serve the best interests of the market and/or consumers. Governments may force such companies to divide into smaller independent corporations as was the case of United States v. AT&T, or alter its behavior as was the case of United States v. Microsoft, to protect consumers.

Monopolies can be established by a government, form naturally, or form by mergers. A monopoly is said to be coercive when the monopoly actively prohibits competitors by using practices (such as underselling) which derive from its market or political influence (see Chainstore paradox). There is often debate of whether market restrictions are in the best long-term interest of present and future consumers.

In many jurisdictions, competition laws restrict monopolies. Holding a dominant position or a monopoly of a market is not illegal in it self, however certain categories of behavior can, when a business is dominant, be considered abusive and therefore incur legal sanctions. A government-granted monopoly or legal monopoly, by contrast, is sanctioned by the state, often to provide an incentive to invest in a risky venture or enrich a domestic interest group. Patents, copyright, and trademarks are all examples of government granted and enforced monopolies. The government may also reserve the venture for itself, thus forming a government monopoly.

3.5. Perfect competition

In economic theory, perfect/pure competition describes markets such that no participants are large enough to have the market power to set the quantity of a homogeneous product. Because the conditions for perfect competition are strict, there are few if any perfectly competitive markets. Still, buyers and sellers in some auction-type markets say for commodities or some financial assets may approximate the concept. Perfect competition serves as a benchmark against which to measure real-life and imperfectly competitive markets.

- Characteristics:

Generally, a perfectly competitive market exists when every participant is a “price taker”, and no participant influences the price of the product it buys or sells. Specific characteristics may include:

- Infinite buyers and sellers – Infinite consumers with the willingness and ability to buy the product at a certain quantity, and infinite producers with the willingness and ability to supply the product at a certain quantity.

- Very few entry and exit barriers – It is relatively easy for a business to enter or exit in a perfectly competitive market.

- Perfect factor mobility – In the long run factors of production are perfectly mobile allowing free long term adjustments to changing market conditions.

- Perfect information – Prices and quality of products are assumed to be different from all producers.

- Zero transaction costs – Buyers and sellers incur no costs in making an exchange (perfect mobility).

- Profit maximization – Firms aim to sell where marginal costs meet Total revenue, where they generate the most profit.

- Homogeneous products – The characteristics of any given market good or service do not vary across suppliers.

- Non-increasing returns to scale – Non-increasing returns to scale ensure that there are sufficient firms in the industry.

In the short term, perfectly-competitive markets are not productively efficient as output will not occur where marginal cost is equal to average cost, but allocatively efficient, as output will always occur where marginal cost is equal to marginal revenue, and therefore where marginal cost equals average revenue. In the long term, such markets are both allocatively and productively efficient.

Under perfect competition, any profit-maximizing producer faces a market price equal to its marginal cost. This implies that a factor’s price equals the factor’s marginal revenue product. This allows for derivation of the supply curve on which the neoclassical approach is based. (This is also the reason why “a monopoly does not have a supply curve.”) The abandonment of price taking creates considerable difficulties to the demonstration of existence of a general equilibrium except under other, very specific conditions such as that of monopolistic competition.

B. Examples

Perhaps the closest thing to a perfectly competitive market would be a large auction of identical goods with all potential buyers and sellers present. By design, a stock exchange resembles this, not as a complete description (for no markets may satisfy all requirements of the model) but as an approximation. The flaw in considering the stock exchange as an example of Perfect Competition is the fact that large institutional investors (e.g. investment banks) may solely influence the market price. This, of course, violates the condition that “no one seller can influence market price”.

Free software works along lines that approximate perfect competition. Anyone is free to enter and leave the market at no cost. All code is freely accessible and modifiable, and individuals are free to behave independently. Free software may be bought or sold at whatever price that the market may allow.

Some believe. that one of the prime examples of a perfectly competitive market anywhere in the world is street food in developing countries. This is so since relatively few barriers to entry/exit exist for street vendors. Furthermore, there are often numerous buyers and sellers of a given street food, in addition to consumers/sellers possessing perfect information of the product in question. It is often the case that street vendors may serve a homogenous product; in which little to no variations in the product’s nature exist.

Another very near example of perfect competition would be the fish market and the vegetable or fruit vendors who sell at the same place, the bars in “Le Carré” (Liège, Belgium) or the “kebab street” near the Grand Place in Brussels

- There are large number of buyers and sellers.

- There are no entry or exit barriers.

- There is perfect mobility of the factors, i.e. buyers can easily switch from one seller to the other.

- The products are homogenous.

Reference:

- Stanlake’s Introductory Economics (7th Edition)

- google.com

- wikipidia.org