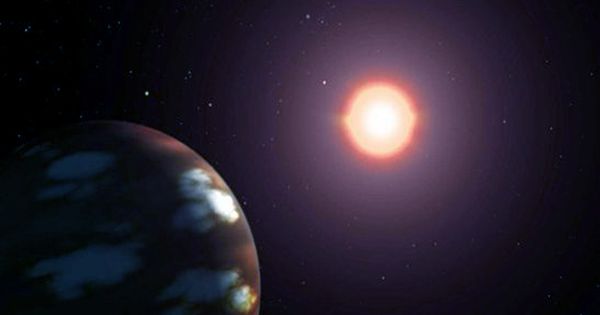

Gas giants can form on easier terms than previously believed. This new insight comes from a detailed investigation of a strange “super-puff” planet, a gas giant that swells near the stars. These planets are often referred to as “cotton-candy” planets due to their low density. As published in The Astronomical Journal, the planet WASP-107b orbits its star 16 times more than the Earth’s Sun, significantly warming this nearby planet. Astronomers estimate it to be larger than Jupiter, containing one-tenth of its mass.

Estimates of this planet suggest that it has a very low density – its core has a mass of about four Earths and the remaining 26 Earth-mass masses are located in its glowing environment. This is more than 85 percent of its mass as a gas envelope – for comparison; Neptune has a gas level of only 5 to 15 percent. This noticeable difference was an important point for this work.

Lead author Caroline Piaulet, a graduate researcher at the University of Montreal, said in a statement, “We had a lot of questions about WASP-107b.” “How could a planet with such a low density take shape? And how did it survive the turn of its massive gas, especially given the planet’s proximity to the stars? This inspired us to do a detailed analysis to determine the history of formation.”

The structure expected for a gas giant like Saturn or Jupiter shows a huge solid center, which is about 10 times larger than Earth, collecting large amounts of gas from a disk of material surrounding a new star. Having a larger core was considered an essential requirement, but WASP-107b shows that this may not be the case.

Co-author Professor Eve Lee added, “For WASP-107b, the most admirable view is that the planet was formed far away from the stars, where the gas in the disk is cold enough that the synthesis of the gas can occur very quickly.” “The planet was later able to move to its current location by interacting with the disk or other planets in the system.”

Finding a planet like this provides solid evidence that a large solid core is not always needed to form a gas giant – there is a process that bypasses it. And in this case, the answer comes from its planetary sibling: WASP-107c. This second planet orbits the star every three years (compared to 5.7 days of WASP-107B) and is about three times as large. However, the main evidence of past embarrassment is that its stimulus is high, meaning that the planet’s orbit is elliptical rather than circular.

Paul explained, “WASP-107c has in some cases left a memory of what happened to its system.” “Its great stimulus hints at a rather chaotic past, in interplanetary interactions that could lead to significant displacement as a suspect for WASP-107b.” WASP-107b was already infamous because it was the first exoplanet where scientists found helium in its atmosphere. The team is hopeful of collecting new observations of interesting planets after JWST comes online at the end of the year.