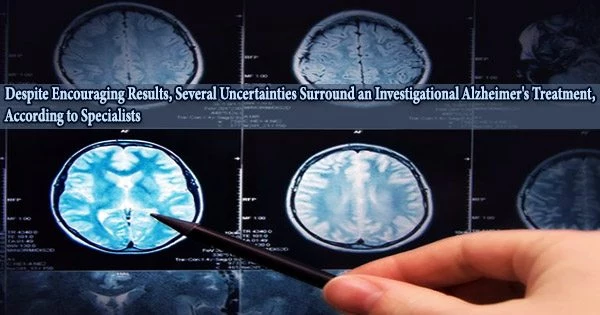

Lecanemab, an investigational medication for Alzheimer’s, made headlines last week when the company studying it disclosed trial findings demonstrating that the treatment achieved its objectives, making it one of the first dementia medications to produce encouraging results.

Lecanemab users had around 27% less decrease after 18 months than lecanemab non-users in a randomized, placebo-controlled study of roughly 1,800 individuals who were in the early stages of memory loss, the company claimed. The difference was equivalent to around half a point on the Clinical Dementia Rating Sum of Boxes, a regularly used scale. The statistical significance of the difference suggests that the improvement wasn’t accidental.

The corporations have only provided a brief summary of the study in a news release, and analysts predict that before they fully comprehend the findings, they will want to delve deeply into the specifics.

But if it succeeds, lecanemab will have bucked a long history of failures in the field.

What’s different this time?

Lecanemab may be the 16th medication created to remove harmful amyloid plaques from the brain. Many of the others eradicated amyloid and performed as promised. The problem is that few few have demonstrated any actual benefit to patients, which has led many specialists to believe that the entire area is, to put it mildly, out of left field.

They said the so-called amyloid hypothesis, which holds that amyloid plaques accumulate in the brain and cause Alzheimer’s disease, is false and urged drug researchers to start over.

So after this long string of a failures, why does lecanemab look like it worked? Is there something about the drug that makes it better? Or did the companies that are testing it Biogen and Eisai run a smarter clinical trial that finally showcased the potential of these kinds of medications?

“It’s actually a combination of both,” said Dr. Michael Irizarry, Eisai’s deputy chief clinical officer for Alzheimer’s and brain health.

Obviously, everybody wants patients to do better the patients, the caregivers, the clinicians and that’s why we rely very heavily on this notion of double blinding so that nobody knows whether you’re getting active treatment or placebo.

Professor Dr. Michael Greicius

Irizarry said that in planning the clinical trial, researchers were able to take advantage of advances in technology, like new kinds of scans that can confirm the presence of beta amyloid in the brain. Previously, doctors could see amyloid in the brain only during autopsies.

They recruited people who were earlier in the course of their disease, at a point where agents like lecanemab could potentially do some good.

“We ensured that we recruited people into the clinical trials that have the target and might be able to respond to the drug,” Irizarry said.

They were also able to learn from missteps with previous treatments, like aducanumab, which is also made by Biogen and Eisai. They included nearly 1,800 people in the last stage of the clinical trial, enough to show a difference between the group taking the drug and the group that got a placebo.

Irizarry says the researchers also used their Phase 2 trial to carefully choose the dosage, and so in Phase 3, all participants randomly assigned to the therapy got the same dose.

Finally, Irizarry says, all antibodies that target amyloid latch onto it at slightly different places. Lecanemab binds to these protein pieces when they have joined together to form chains of amyloid pieces called protofibrils, but before these chains clump together to form plaques in the brain. It could be that catching the amyloid earlier in the process makes a difference, too.

Waiting on more data

Some independent experts have doubts that it’s a big breakthrough, however.

“I don’t think we’re seeing a clinical benefit that’s that different from aducanumab,” said Dr. Constantine Lyketsos, a psychiatrist and professor at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine.

Aducanumab, sold as Aduhelm, was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in June 2021, over the objections of the agency’s panel of outside advisers. Clinical trial results were mixed, with only one showing a small benefit to patients. Medicare agreed to cover the drug only under certain circumstances, and it has become a commercial flop.

“The major difference is that lecanemab had a much larger sample size,” Lyketsos said.

If you superimposed the results seen with lecanemab over those seen with aducanumab in the study where it showed a positive result, he says, you’d see about the same degree of benefit.

“I think we’re seeing a successful strategic approach by the companies developing it to have a very large study that was big enough to detect a small effect,” he said.

Lyketsos is also worried about brain swelling called ARIA, short for amyloid-related imaging abnormalities. These side effects have been seen with other types of amyloid-clearing antibodies and happened in about 1 in 5 of participants taking lecanemab.

The protofibrils that the drug targets line the walls of the blood vessels in the brain, he said. When they’re removed, the vessels can leak fluid or blood into the brain. If enough leaks out, it shows up on an MRI.

Some people who get ARIA don’t have any symptoms. But occasionally, they can be more serious, leading to hospitalization or lasting impairment.

Lyketsos says experts don’t yet understand what happens when mild ARIAs come and go repeatedly or how common a catastrophically bad case of brain swelling may be.

If lecanemab has been infused in only a few thousand people, that may not be a large enough sample to know whether cases of more severe brain swelling may show up as rare events.

“Maybe there is no such catastrophe. We just don’t know,” he said. “So a lot of drugs like this, if it were to come on the market, would have this big asterisk next to it that says we really don’t know about the long-term safety.”

Lyketsos says he would be really challenged to offer lecanemab to a patient.

“If it was a simple pill, if it wasn’t very expensive, I might,” he said. But given the likely cost of the medication aducanumab, for example, now costs about $28,000 for a year of treatment and the slight degree of slowing of the progression of the disease, it would be hard.

The price for lecanemab will be announced only if it’s approved by the FDA.

He says he might change his mind if analysis of the clinical trial shows that one group of people got more of a benefit than others.

Eisai’s Irizarry says the company is analyzing the trial results for that exact issue right now – whether people with genetic risks for Alzheimer’s, or perhaps those with complicating health conditions like diabetes or high blood pressure, may have responded differently to the treatment.

“It’s definitely an area that we are working on,” he said.

Benefit or bias?

Other experts worry that the trial was skewed because those ARIA events which happen only in people who get anti-amyloid antibodies essentially revealed to doctors and patients that they were getting the medication, thus unblinding the study.

The main measure used to evaluate participants in the study was a survey that ranks how well they are functioning in six areas of their lives, including memory, orientation and problem-solving. It relies, in large part, on the assessment of the person’s primary caregiver.

“That’s very prone to bias,” said Dr. Michael Greicius, a neurologist and professor at Stanford University.

“Obviously, everybody wants patients to do better the patients, the caregivers, the clinicians and that’s why we rely very heavily on this notion of double blinding so that nobody knows whether you’re getting active treatment or placebo,” he said.

People getting the treatment which is given by IV infusion once every two weeks can have reactions that include shaking, chills and a low-grade fever.

Greicius says nobody has come up with a solution for how to mask study participants to these very prominent side effects, which require that participants get extra brain scans and pause their treatments.

“I want to be convinced that this is actually moving the needle, but I need to see a little more evidence for that,” he said.

Another expert thinks lecanemab may work to a degree, but not for the reasons people suppose.

Dr. Alberto Espay, a neurologist at the University of Cincinnati, says that in addition to removing beta amyloid from the brain, lecanemab increases levels of the normal version of the amyloid protein, called AB42.

This version of the protein is integral to the structure and function of the brain, he says, and his studies have shown that loss of it is most closely correlated to cognitive decline, rather than the buildup of amyloid plaques. However, he admits that this idea is not a mainstream theory in Alzheimer’s research.

Espay says he would never consider giving these kinds of drugs to his patients, not only because their benefits are small but because the costs could be staggering. If millions of people are put on them, we’ll all pay the price, he says.

In November, Medicare announced that it was raising the monthly premiums for its Part B plan, in part because of its expected spending on aducanumab.

In a statement emailed to CNN, Eisai says it hasn’t yet priced lecanemab, but that it is sensitive to concerns about the cost of the drug.

“In the U.S., Eisai’s approach to pricing will be based on a modeling framework that considers the results of the Clarity AD trial, with consideration to the sustainability of the healthcare system and a level of affordability for the people living with early AD,” spokesperson Christopher Vancheri wrote.

These medications “are going to break the health-care system,” Espay said. “If they were really good for patients, then yes, let’s break the health-care system, because it’s going to make a difference.

“It cannot make a difference.”