What connects a finger bone and some fossil teeth discovered in a cave in the remote Altai Mountains of Siberia to a single tooth discovered in a cave in tropical Laos’ limestone landscapes? An international team of researchers from Laos, Europe, the United States, and Australia has established the answer to this question.

The human tooth was discovered during an archaeological survey in a remote area of Laos. Scientists have established that it descended from the same ancient human population discovered in Denisova Cave (dubbed the Denisovans) in Siberia’s Altai Mountains (Russia).

The research team made the significant discovery during their 2018 excavation campaign in northern Laos. The new cave Tam Ngu Hao 2, also known as Cobra Cave, is located near to the famous Tam Pà Ling Cave where another important 70,000-year-old human (Homo sapiens) fossils had been previously found.

Despite being thousands of kilometers apart, international researchers are confident that the two ancient sites are linked to Denisovan occupations. Their findings, led by The University of Copenhagen, the CNRS (France), the University of Illinois Urbanna-Champain (USA), the Ministry of Information Culture and Tourism, Laos, and supported by microarchaeological work at Flinders University and geochronological analyses at Macquarie University and Southern Cross University in Australia, were published in Nature Communications.

After all this work following the many clues written on fossils from very different geographic areas our findings are significant. This fossil represents the first discovery of Denisovans in Southeast Asia and shows that Denisovans were in the south at least as far as Laos. This is in agreement with the genetic evidence found in modern day Southeast Asian populations.

Professor Demeter

Fabrice Demeter, lead author and Assistant Professor of Palaeoanthropology at the University of Copenhagen, says the cave sediments contained the teeth of giant herbivores, ancient elephants, and rhinos known to live in woodland environments.

“After all this work following the many clues written on fossils from very different geographic areas our findings are significant,” Professor Demeter says. “This fossil represents the first discovery of Denisovans in Southeast Asia and shows that Denisovans were in the south at least as far as Laos. This is in agreement with the genetic evidence found in modern day Southeast Asian populations.”

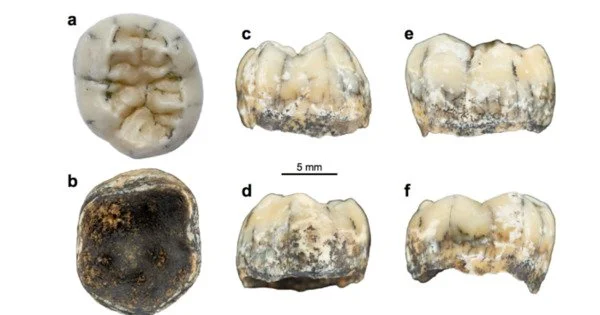

Following a thorough examination of the tooth’s shape, the researchers discovered many similarities to Denisovan teeth discovered on the Tibetan Plateau, the only other location where Denisovan fossils have been discovered. This indicated that it was most likely a Denisovan who lived between 164,000 and 131,000 years ago in northern Laos’ warm tropics.

According to Associate Professor Mike Morley of Flinders University’s Microarchaeology Laboratory, the cave site known as Tam Ngu Hao 2 (Cobra cave) was discovered high up in the limestone mountains and contained remnants of an old cemented cave sediment packed with fossils.

“We have essentially found the ‘smoking gun’ — this Denisovan tooth shows they were once present this far south in the karst landscapes of Laos,” says Associate Professor Morley.

The complexity of the site created a challenge for dating and required two Australian teams. The team from Macquarie University, led by Associate Professor Kira Westaway, provided dating of the cave sediments surrounding the fossils; and the team from Southern Cross University led by Associate Professor Renaud Joannes-Boyau conducted the direct dating of unearthed fossil remains.

“Establishing a sedimentary context for the fossils’ final resting place provides an internal check on the integrity of the find- if the sediments and fossils return a similar age, as seen in Tam Ngu Hao 2, then we know that the fossils were buried not long after the organism died,” says Associate Professor Kira Westaway.

Direct dating of fossil remains is critical if we are to understand the succession of events and species in the landscape.

“The good agreement of the different dating techniques on both sediment and fossils attests to the quality of the chronology for the species in the region. And this has significant implications for population mobility in the landscape “Prof Renaud Joannes-Boyau of Southern Cross University says.

The fossils were probably scattered across the landscape before being washed into the cave during the flooding event that deposited the sediments and fossils. Unfortunately, unlike Denisova Cave, the ancient DNA in Laos was not preserved due to the humid conditions. However, the archaeological scientists discovered ancient proteins that indicated the fossil was a young, likely female, human aged between 3.5 and 8.5 years.

The discovery suggests that Southeast Asia was a hotspot of human diversity, with at least five different species setting up camp at various times: Homo erectus, Denisovans/Neanderthals, H. floresiensis, H. luzonensis, and H. sapiens. Southeast Asian caves could provide the next clue and hard evidence to help researchers better understand these complex demographic relationships.