Petroleum is evident all over the Santa Barbara Channel, from oil rigs to tar leaks. And because UC Santa Barbara is nearby, researchers have been able to examine how regional geology and human activity interact to release oil from underground.

Emeritus Professor James Boles collected and analyzed decades of data on methane seeping from the seafloor southeast of Platform Holly, just offshore from Isla Vista. He and colleagues Grant Garven at Tufts University and Chris Peltonen at Beacon West Energy Group determined that production of oil and natural gas from the platform reduced natural methane seepage into the waters of the Santa Barbara Channel, confirming earlier regional studies. The findings appear in the journal Marine and Petroleum Geology.

“The gas production from Platform Holly has reduced natural seepage in this area over short time periods, resulting in a significant reduction in greenhouse gas emissions,” Boles said. “And hydrocarbon production can reduce natural seepage in areas with similar geologic settings.”

Compared to many of the world’s reserves, the Santa Barbara Channel’s petroleum deposits are relatively new. Between 16 million and 5 million years ago, sediment containing organic material was buried, and over the course of time and temperature, the organic material was converted to oil and gas. Shale was formed from the sediment, and the area underwent deformation that folded and split the rock, allowing fluids to travel through it.

In many respects the South Ellwood Oil Field is typical of deposits in the Santa Barbara Channel. Yet, it is situated in relatively shallow water close to the shore, and the layer of contemporary marine silt that covers it is often even nonexistent.

The gas production from Platform Holly has reduced natural seepage in this area over short time periods, resulting in a significant reduction in greenhouse gas emissions. And hydrocarbon production can reduce natural seepage in areas with similar geologic settings.

Professor James Boles

A few kilometer or two below the seafloor, the oil has also collected close to the surface. Due to the area’s extensive faulting, a lot of oil and gas naturally seeps out along this section of coast.

Humans have known about the oil deposits near Ellwood since time immemorial. Tar was used by the Chumash, and asphalt mines existed beneath the present UC Santa Barbara campus. The South Ellwood Oil Field was discovered onshore in the 1930s, but wasn’t extensively developed offshore until the 1960s.

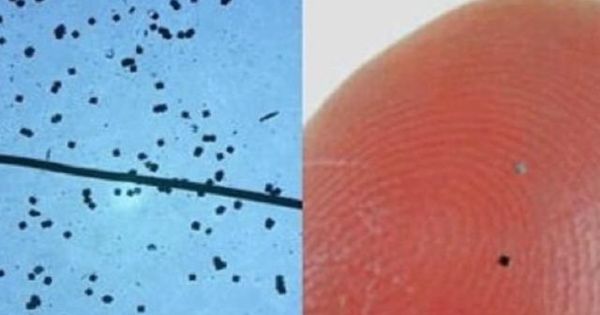

Platform Holly was installed in 1966, and had 30 active wells at any given time, which could extend up to 1.5 miles from the rig. In 1982, the Atlantic Richfield Company (ARCO) installed two steel tents to capture methane seeping near Platform Holly.

“The two steel pyramids, referred to as tents, are each 100 feet by 100 feet and weigh 350 tons,” Boles said. The installation cost the company $8 million, equivalent to around $25 million in 2023. Methane from the platform and the seep tents were piped into the Southern California gas supply.

The tents gave researchers a rare opportunity to examine natural seepage over a vast area of the ocean floor. Boles took advantage of the chance and, in 1994, requested that the business place a measurement device on the gas flow line.

The team examined data spanning 20 years and discovered that Platform Holly’s output dramatically decreased the amount of methane leaking into the tents. For example, production from a well drilled 1 kilometer beneath the tents immediately reduced the natural seepage. In contrast, the seepage increased when production ceased from that well.

“This indicates a direct link between the oil reservoir and the natural seepage in the area,” Boles noted.

Other forces also influenced the amount of gas bubbling up from the depths. The authors discovered small changes in the rate of seepage corresponding to the tides. High tides suppressed seepage by about 8%, whereas low tides had the opposite effect.

Gas stopped flowing into the tents in the summer of 2013, when a new well was drilled just beneath them and produced large quantities of gas. Platform Holly ceased production altogether in 2015, and is currently being decommissioned.

Although no methane is currently seeping into the tents, the area is still active. Long-term employees and supply boat personnel have observed a significant rise in gas seepage, which bubbles to the surface surrounding the platform, since Holly shut down.

Methane is around 25 times more potent than CO2 as a greenhouse gas over the period of a century, thus even little amounts can have an excessive warming effect. Given that methane would vent from this area anyway, harnessing the gas could actually reduce the greenhouse gas emissions from the South Ellwood Oil Field.

“It is important to understand that these natural seeps will continue,” Boles said. “In our area, it might be possible to capture additional natural methane seeps using sea floor devices.”