EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Cross-cultural negotiations is the interactions, typically in business, that occur between various cultures. These negotiations are typically viewed as occurring between various nations, but cross-cultural studies can also occur between different cultures within the same nation, such as between European-Americans and Native Americans. As the world becomes more and more interdependent as a result in the expansion of globalization and international business relations, cross-cultural negotiations are becoming a common feature in business and political transactions. This being the case, understanding how cross-cultural negotiations occur is an important skill to have. Thus, there has been an abundance of research and literature conducted and written on the topic.

Culture is a group-level phenomenon. Although each group essentially consists of individuals and despite the fact that culture is manifested through individuals, culture itself is a phenomenon that can only be observed once it is shared by the vast majority of the individuals belonging to a certain group. Culture is acquired by individuals from the group they belong to either through socialization or acculturation. This implies that culture not only has to be shared by the individuals belonging to a certain group but also that it has to be preserved in time and transmitted from one generation to another.

There are several ways in which to resolve the conflict. If one party is significantly more dominant (powerful) than another, they could attempt to simply enforce their will on the other. Other times, both parties may choose to enlist the aid of an outside neutral party to “mediate” the issue. Generally, the mediator’s role is that of a facilitator, bringing the parties together and assisting them to work through the particular issue. Another tool for conflict resolution involves the use of an “arbitrator.” There are generally two types of arbitration; binding and non-binding. In both cases the arbitrator hears the positions of both parties and then renders a decision. In binding arbitration, both parties are “bound” to the decision. Under the non-binding case, either party is free to disregard the arbitrator’s decision.

CROSS CULTURAL NEGOTIATION

Introduction.

Cross-cultural negotiations is the interactions, typically in business, that occur between various cultures. These negotiations are typically viewed as occurring between various nations, but cross-cultural studies can also occur between different cultures within the same nation, such as between European-Americans and Native Americans. As the world becomes more and more interdependent as a result in the expansion of globalization and international business relations, cross-cultural negotiations are becoming a common feature in business and political transactions. This being the case, understanding how cross-cultural negotiations occur is an important skill to have. Thus, there has been an abundance of research and literature conducted and written on the topic. What follows is a brief review of the current literature available on the topic of cross-cultural negotiations.I.Hendon, Donald W., Herbig, Paul and Rebecca Angeles Hendon.(1999).Cross-Cultural Business Negotiations. New York: Greenwood Publishing Group,Inc.

Aim

Each of the variables discussed in this module — time and space, personal responsibility and fate, face and face-saving, and nonverbal communication — are much more complex than it is possible to convey. Each of them influences the course of communications, and can be responsible for conflict or the escalation of conflict when it leads to miscommunication or misinterpretation. A culturally-fluent approach to conflict means working over time to understand these and other ways communication varies across cultures, and applying these understandings in order to enhance relationships across differences.

What is culture.

There are numerous definitions of culture in the literature. Kroeber and (1963), for instance, have collected more than 160 of them. Despite the fact that some researcher consider the concept of culture not well defined,most of the definitions, share three key features. Culture is a group-level phenomenon. Although each group essentially consists of individuals and despite the fact that culture is manifested through individuals, culture itself is a phenomenon that can only be observed once it is shared by the vast majority of the individuals belonging to a certain group. Culture is acquired by individuals from the group they belong to either through socialization or acculturation. This implies that culture not only has to be shared by the individuals belonging to a certain group but also that it has to be preserved in time and transmitted from one generation to another.

Working Definitions- Culture

Guy Olivier Faure attributes the 20th century French writer and politician Herriot, with this definition of culture: it is “what remains when one has forgotten everything”. Faure’s reason for quoting Herriot is to point out that culture is more a way of an individual’s actions of which they are usually unaware. Culture is a product that reveals itself in social behaviors like beliefs, ideas, language, customs and rules. Faure attempts to capture the specific concept of culture by defining it as “a set of shared and enduring meanings, values, and beliefs that characterize national, ethnic, or other groups and orient their behavior”.Cohen further expands on the understanding of culture by addressing three key aspects: it is a societal and not an individualistic quality; it is acquired not genetic, and that its attributes cover the entire array of social life.

From the first aspect, it is the society to which the individual associates that will dictate the norms; not the individual. Cohen uses the example of the “blood feud” within a clan-based society. He postulates that regardless of the individual’s personal feelings toward retribution, even in the extreme form, he or she is bound to the actions of the clan so long as the individual decides to remain part of the clan. The second feature attributes culture to the methods that develop the cultural norms within the individual members. These methods are both formal and informal. The formal methods include education, role models, propaganda and the culture’s system for rewards and punishments . The informal methods are comprised of how members assimilate influences framed by their environment; for example, family life and social encounters at both work and play. Cohen’s third feature conveys that culture is not just about the artifacts that members surround themselves with, but that there are intellectual and organizational dimensions as well. The artifacts are the most visible aspects of a group’s culture. But a culture’s identity is also rooted in “intangibles” that include etiquette conventions, the manner in which interpersonal relationships are conducted, and how a member’s life and actions should be conducted .

Mental Programs

In his book, Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind, Geert Hofstede postulates that: Every person carries within himself or herself patterns of thinking, feeling and potential acting which were learned throughout their lifetime. Much of it has been acquired in early childhood, because at that time a person is most susceptible to learning and assimilating. As soon as certain patterns of thinking, feeling and acting have established themselves within a person’s mind, (s)he must unlearn these before being able to learn something different, and unlearning is more difficult than learning for the first time .

Hofstede terms these patterns as “mental programming” and quantifies that culture, unlike human nature and personality, is singularly a learned trait (Appendix-1).

As Appendix- 1 depicts, human nature contains those characteristics that all humans have in common. It is an inherited “mental software” . For example, human nature contains those universally shared traits of fear, anger, the need to interact with others…the “basic psychological functions” . The crossover into culture is related to what an individual does with these feelings.

Personality contains an individual’s unique mental programs. Some of the programs are genetically inherited while others are learned. Hofstede defines learning in this area as “modified by the influence of collective programming (culture) as well as unique personal experiences” . Hofstede defines culture as “the collective programming of the mind which distinguishes the members of one group or category of people from another” (10:5). One element, that on the face of his definition may appear to be missing, at least in relation to the previous definitions given, is the aspect of values as it relates to culture. Figure 2 depicts Hofstede’s “onion diagram” with values at its core (Appendix-2). Like peeling back the layers of an onion until the core is reached, the diagram reveals four elements of culture. The first three layers, symbols, heroes, and rituals represent those layers of culture that are visible to outsiders. These are the “practices” of a given culture but their cultural meaning (emphasis added) may not be obvious to those who are not a part of that culture .

Symbols are placed at the outer layer because they are most visible to outsiders and can be exchanged between cultures. Examples include language (and jargon), dress, gestures, and status symbols . As the name implies, heroes are persons, real or imagined (Superman for the U.S.), that are held in high regard by a culture . Rituals represent the third layer. They are considered “socially essential” within a culture and consist of methods of greeting, levels of respect, and various ceremonial observances. The cultural core, according to Hofstede, is formed by the individual and collective values of the group.

Values

Hofstede describes values as those “broad tendencies to prefer certain states of affairs over others” . Shalom Schwartz’s research in this area helps to frame the concept of cultural values. The Schwartz Value Inventory (SVI) is the result of his research survey of over 60,000 people worldwide and resulted in ten value types. Table 1 lists the SVI and provides a brief description of each value type .

Table 1. Schwartz Value Inventory

| Value Type | Description (Value association) |

| Power | Social status and prestige. The ability to control others is important and power will be actively sought through dominance and control. |

| Achievement | Setting and achieving goals. When others have reached the same level of achievement, status is reduced thus greater goals are sought. |

| Hedonism | Seek pleasure above all things. |

| Stimulation | Closely related to hedonism but pleasure is derived from excitement and thrills. |

| Self-direction | Independent and outside the control of others. Prefer freedom. |

| Universalism | Social justice and tolerance for all. Promote peace and tolerance for all. |

| Benevolence | Very giving; seeks to help others and provide general welfare. |

| Tradition | Respect for things that have gone before. Customary; change is uncomfortable. |

| Conformity | Seeks obedience to clear rules and structures |

| Security | Seeks health and safety to a greater degree than others |

Although discussions of values tend to gravitate toward the individual, value domains can also be construed from a collectivist or a combination individual/collectivist as well. Hedonism, power, achievement and self-direction clearly serve individual interest; tradition, conformity and benevolence serve collective interests; security, universalism, and spirituality serve individual and collective interests. From the discussion thus far culture orients behavior; is a singularly learned trait and thus differs from, but is influenced by, personality and human behavior; its attributes cover the entire array of social life; it dictates how interpersonal relationships are conducted and at its core are the values the culture, and by extension its individual members, internalize. This understanding of culture is central to the following discussion on the dimensions of culture.

Power Distance Index (PDI). Power distance is “the extent to which the less powerful members of institutions and organizations within a country expect and accept (emphasis added) that power is distributed unequally” . The power distance dimension is a measure of the relationships between individuals of different status within a culture . Table 2 illustrates the salient characteristics of the PDI.

Table 2. Low and High Power Distance Cultures

| Low PDI | High PDI |

| General Norms (Values) | |

| Inequalities among people should be minimized | Inequalities among people are both expected and desired |

| Interdependence between less and more powerful people | Less powerful people should be dependant on the more powerful |

| Hierarchy means an inequality of roles | Hierarchy reflects existential inequality |

| Decentralization preferred | Centralization preferred |

| Students treat teachers as equals | Students treat teachers with respect |

| Children treat parents as equals | Children treat parents with respect |

| Implications | |

| Subordinates expect to be consulted | Subordinates expect to be told |

| Bosses expect feedback | Bosses expect obedience |

| Privileges/status symbols frowned upon | Perks/privileges are natural |

| Individual initiative encouraged | Subordinates always seek permission |

| Example Cultures | |

| Australia | Malaysia |

| Israel | Panama |

| Denmark | Philippines |

| New Zealand | Mexico |

| Great Britain | Arab Countries |

Individualism Index (IDV). Individualism, as used in this index, is the degree to which people in a country or region learn to interact with each other. The majority of the people of the world live in societies where they are taught from birth that the interest of the group, starting with the extended family, is paramount to the interest of the individual . These are described as collectivist societies. The reverse is the case for the individualist societies. Hofstede defines this dimension as such:

“Individualism pertains to societies in which ties between individuals are loose: everyone is expected to look after himself…and his or her immediate family. Collectivism as it’s opposite pertains to societies in which people from birth onwards are integrated into strong, cohesive in-groups, which throughout people’s lifetime continue to protect them in exchange for unquestioned loyalty” .

Table 3 provides sample characteristics of the IDV

Table 3. Low and High Individualism Cultures

| Low IDV (Collectivist) | High IDV (Individualist) |

| General Norms (Values) | |

| People are born into extended families | People grow up to look after him/herself and the immediate family |

| Identity is based on your social network | Identity based on the individual |

| High context communications | Low context communication |

| Diplomas provide entry to higher status groups | Diplomas increase economic worth/self-respect |

| Employer-employee relationship perceived in moral terms; like a family link | Employer-employee relationship is a contract based on mutual advantage |

| Management of groups | Management of people |

| Implications | |

| Maintain harmony; avoid conflict | Speaking your mind is admirable |

| Social network is primary source of info | Media is primary source of info |

| Relationship prevails over task | Task prevails over relationship |

| Example Cultures | |

| Guatemala | USA |

| Panama | Australia |

| Indonesia | Great Britain |

| Pakistan | Canada |

| Taiwan | Italy |

| South Korea | Belgium |

| West Africa | Denmark |

Masculinity Index (MAS): The masculinity-femininity dimension identifies cultural variability based on what are considered appropriate gender roles for that culture. …masculinity pertains to societies in which social gender roles are clearly distinct (i.e., men are supposed to be assertive, tough, and focused on material success whereas women are supposed to be more modest, tender and concerned with the quality of life); Femininity pertains to societies in which social gender roles overlap i.e. both men and women are supposed to be modest, tender, and concerned with the quality of life .

Table 4 provides sample characteristics of the MAS.

Table 4. Low and High Masculinity Cultures

| Low MAS (Feminine) | High MAS (Masculine) |

| General Norms (Values) | |

| Dominate values in society are caring for others and preservation | Dominate values in society are material success and progress |

| People and relationships are important | Money and things are important |

| Failing in school is a minor accident | Failing in school is a disaster |

| Managers use intuition & strive for consensus | Managers expected to be decisive & assertive |

| Work to live | Live to work |

| Implications | |

| Roles of sexes are undifferentiated | Defined masculine/feminine sex roles |

| Example Cultures | |

| Sweden | Japan |

| Norway | Austria |

| Netherlands | Venezuela |

| Denmark | Italy |

| Costa Rica | Great Britain |

| Finland | USA |

Uncertainty Avoidance Index (UAI). “Extreme uncertainty creates intolerable anxiety. Every human society has developed ways to alleviate this anxiety. These ways belong to the domains of technology, law and religion” . In the context that Hofstede uses, uncertainty avoidance is not the same as risk avoidance. Ambiguity is the root cause of uncertainty avoidance, with risk-taking a by-product of attempts to mitigate ambiguity. As such, cultures scoring high on the uncertainty avoidance index (low tolerance for ambiguity) look for structure in their organizations, institutions and relationships in order to reduce the ambiguity and thus risk. Table- 5 demonstrates the important characteristics in this dimension. Describing the cultural dimensions will assist in understanding the cultural impact on negotiations. But first, it is necessary to lay the framework for comparison by providing insights into negotiation

Table 5. Low and High Uncertainty Avoiding Cultures

| Low UAI (High tolerance for Ambiguity) | High UAI (Low tolerance for Ambiguity) |

| General Norms (Values) | |

| Uncertainty is a normal feature of life | Uncertainty inherent in life is felt as a continuous threat that must be fought |

| Low stress; subjective feeling of well being | High stress; subjective feeling of anxiety |

| Aggression and emotions should not be shown | Aggression and emotions at proper times may be expressed |

| Comfortable in ambiguous situations and with unfamiliar risks | Acceptance of familiar risks; fear of ambiguous situations and of unfamiliar risks |

| Few and general laws and rules | Many and precise laws and rules |

| Tolerance, moderation | Conservatism, extremism, law and order |

| Internationalism, regionalism | Nationalism, xenophobia |

| Precision and punctuality have to be learned | Precision and punctuality come naturally |

| Time is a framework for orientation | Time is money |

| Implications | |

| Belief in generalist and common sense | Belief in experts and technical solutions |

| Focus on decision process | Focus on decision content |

| No more rules than strictly necessary | Emotional need for rules even if they don’t work |

| Desire for opportunity | Desire for security |

| Results attributed to ability | Results attributed to luck |

| Example Cultures | |

| Singapore | Greece |

| Jamaica | Portugal |

| Denmark | Uruguay |

| Sweden | Belgium |

| Great Britain | Japan |

| USA | France |

What is Negotiation.

When two or more parties (individuals, clubs, nations, etc) reach a position where their interests or values come in conflict with one another .

There are several ways in which to resolve the conflict. If one party is significantly more dominant (powerful) than another, they could attempt to simply enforce their will on the other. Other times, both parties may choose to enlist the aid of an outside neutral party to “mediate” the issue. Generally, the mediator’s role is that of a facilitator, bringing the parties together and assisting them to work through the particular issue. Another tool for conflict resolution involves the use of an “arbitrator.” There are generally two types of arbitration; binding and non-binding. In both cases the arbitrator hears the positions of both parties and then renders a decision. In binding arbitration, both parties are “bound” to the decision. Under the non-binding case, either party is free to disregard the arbitrator’s decision.

Another approach would be to attempt to settle the issue through a process in which the parties interact in a manner that will eventually bring about an agreement that would resolve the issue in controversy. The third approach falls into the realm of negotiations with definitional characteristics that separate it from the other types of resolution.

P.H. Gulliver Refines the Definition further:

Negotiations are processes of interaction between disputing parties whereby, without compulsion by a third party adjudicator, they endeavor to come to an interdependent, joint decision concerning the terms of agreement on the issues between them. This joint decision is one that, in the end, is agreeable to and accepted by both parties after each has brought influence and persuasion to bear on the other and, most probably, after both have experienced influence from other sources. The outcome is essentially one that, in each party’s opinion in the perceived circumstances, is at least satisfactory enough and is perhaps considered to be the best that is obtainable. It often represents a compromise between the parties’ initial demands and expectations, but there may be…the joint creation of some new terms not originally conceived of by either party

Negotiation Continuum

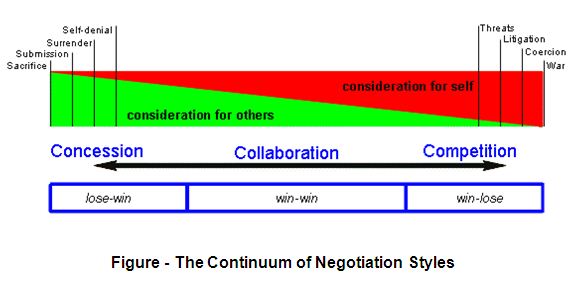

A review of the research on negotiations reveals the style a negotiator utilizes is generally grouped into one of three types: competitive, collaborative and/or concession . The competitive style is also referred to as contending, distributive bargaining, or claiming value . This negotiation style attempts to gain optimum value at the expense of the other party and is commonly referred to as the “win-lose” approach . The collaborative style, also referred to as problem-solving, integrative bargaining, or creating value , attempts to reach agreement through creating options that are conducive to achieving or maximizing the goals of both parties thus creating a “win-win” situation. In the concession or yielding style one party reduces their position to the gain of the other party . This is referred to as the “lose-win” style. In practice, negotiations will take on varying degrees of these styles throughout the process for various reasons. For example, as the definitions provided previously demonstrate, negotiations by their nature reflect different players vying for opposing objectives and interests. In the early stages of negotiations, as each party is attempting to influence the process, gather information previously unknown, and establishing each other’s trust boundaries, a competitive environment may exist until these issues can be resolved. Following Figure provides a graphical depiction of the negotiation continuum . Negotiations strive to achieve a joint decision or outcome satisfactory to both parties. As such, the most effective form of negotiations as a problem-solving approach falls within the collaboration range of the continuum .

Features Of Cross Culture Negotiation:

All communication is cultural — it draws on ways we have learned to speak and give nonverbal messages. We do not always communicate the same way from day to day, since factors like context, individual personality, and mood interact with the variety of cultural influences we have internalized that influence our choices. Communication is interactive, so an important influence on its effectiveness is our relationship with others. Do they hear and understand what we are trying to say? Are they listening well? Are we listening well in response? Do their responses show that they understand the words and the meanings behind the words we have chosen? Is the mood positive and receptive? Is there trust between them and us? Are there differences that relate to ineffective communication, divergent goals or interests, or fundamentally different ways of seeing the world? The answers to these questions will give us some clues about the effectiveness of our communication and the ease with which we may be able to move through conflict.

The challenge is that even with all the good will in the world, miscommunication is likely to happen, especially when there are significant cultural differences between communicators. Miscommunication may lead to conflict, or aggravate conflict that already exists. We make — whether it is clear to us or not quite different meaning of the world, our places in it, and our relationships with others. In this module, cross-cultural communication will be outlined and demonstrated by examples of ideas, attitudes, and behaviors involving four variables:

- Time and Space

- Fate and Personal Responsibility

- Face and Face-Saving

- Nonverbal Communication

As our familiarity with these different starting points increases, we are cultivating cultural fluency — awareness of the ways cultures operate in communication and conflict, and the ability to respond effectively to these differences.

Time and Space

Time is one of the most central differences that separate cultures and cultural ways of doing things. In the West, time tends to be seen as quantitative, measured in units that reflect the march of progress. It is logical, sequential, and present-focused, moving with incremental certainty toward a future the ego cannot touch and a past that is not a part of now. Novinger calls the United States a “chronocracy,” in which there is such reverence for efficiency and the success of economic endeavors that the expression “time is money” is frequently heard. This approach to time is called monochromic — it is an approach that favors linear structure and focus on one event or interaction at a time. Robert’s Rules of Order, observed in many Western meetings, enforce a monochromic idea of time.

In the East, time feels like it has unlimited continuity, an unraveling rather than a strict boundary. Birth and death are not such absolute ends since the universe continues and humans, though changing form, continue as part of it. People may attend to many things happening at once in this approach to time, called polychromous. This may mean many conversations in a moment (such as a meeting in which people speak simultaneously, “talking over” each other as they discuss their subjects), or many times and peoples during one process (such as a ceremony in which those family members who have died are felt to be present as well as those yet to be born into the family).

A good place to look to understand the Eastern idea of time is India. There, time is seen as moving endlessly through various cycles, becoming and vanishing. Time stretches far beyond the human ego or lifetime. There is a certain timeless quality to time, an aesthetic almost too intricate and vast for the human mind to comprehend. Consider this description of an anon, the unit of time which elapses between the origin and destruction of a world system: “Suppose there is a mountain, of very hard rock, much bigger than the Himalayas; and suppose that a man, with a piece of the very finest cloth of Benares, once every century should touch that mountain ever so slightly — then the time it would take him to wear away the entire mountain would be about the time of an Aeon.”

Differences over time can play out in painful and dramatic ways in negotiation or conflict-resolution processes. An example of differences over time comes from a negotiation process related to a land claim that took place in Canada. First Nations people met with representatives from local, regional, and national governments to introduce themselves and begin their work. During this first meeting, First Nations people took time to tell the stories of their people and their relationships to the land over the past seven generations. They spoke of the spirit of the land, the kinds of things their people have traditionally done on the land, and their sacred connection to it. They spoke in circular ways, weaving themes, feelings, ideas, and experiences together as they remembered seven generations into the past and projected seven generations forward.

When it was the government representatives’ chance to speak, they projected flow charts showing internal processes for decision-making and spoke in present-focused ways about their intentions for entering the negotiation process. The flow charts were linear and spare in their lack of narrative, arising from the bureaucratic culture from which the government representatives came. Two different conceptions of time: in one, time stretches, loops forward and back, past and future are both present in this time. In the other, time begins with the present moment and extends into the horizon in which the matters at hand will be decided.

Neither side felt satisfied with this first meeting. No one addressed the differences in how time was seen and held directly, but everyone was aware that they were not “on the same page.” Each side felt some frustration with the other. Their notions of time were embedded in their understandings of the world, and these understandings informed their common sense about how to proceed in negotiations. Because neither side was completely aware of these different notions of time, it was difficult for the negotiations to proceed, and difficult for each side to trust the other. Their different ideas of time made communication challenging.

This meeting took place in the early 1990s. Of course, in this modern age of high-speed communication, no group is completely disconnected from another. Each group — government and First Nations representatives — has had some exposure to the other’s ideas of time, space, and ideas about appropriate approaches to negotiation. Each has found ways to adapt. How this adaptation takes place, and whether it takes place without one side feeling they are forced to give in to the other, has a significant impact on the course of the negotiations.

It is also true that cultural approaches to time or communication are not always applied in good faith, but may serve a variety of motives. Asserting power, superiority, advantage, or control over the course of the negotiations may be a motive wrapped up in certain cultural behaviors (for example, the government representatives’ detailed emphasis on ratification procedures may have conveyed an implicit message of control, or the First Nations’ attention to the past may have emphasized the advantages of being aware of history). Culture and cultural beliefs may be used as a tactic by negotiators; for this reason, it is important that parties be involved in collaborative-process design when addressing intractable conflicts. As people from different cultural backgrounds work together to design a process to address the issues that divide them, they can ask questions about cultural preferences about time and space and how these may affect a negotiation or conflict-resolution process, and thus inoculate against the use of culture as a tactic or an instrument to advance power.

Any one example will show us only a glimpse of approaches to time as a confounding variable across cultures. In fact, ideas of time have a great deal of complexity buried within them. Western concepts of time as a straight line emanating from no one in particular obscure the idea that there are purposive forces at work in time, a common idea in indigenous and Eastern ways of thought. From an Eastern or indigenous perspective, Spirit operates within space and time, so time is alive with purpose and specific meanings may be discerned from events. A party to a negotiation who subscribes to this idea of time may also have ideas about fate, destiny, and the importance of uncovering “right relationship” and “right action.” If time is a circle, an unraveling ball of twine, a spiral, an unfolding of stories already written, or a play in which much of the set is invisible, then relationships and meanings can be uncovered to inform current actions. Time, in this polychromic perspective, is connected to other peoples as well as periods of history.

This is why a polychromic perspective is often associated with a communitarian starting point. The focus on the collective, or group, stretching forward and back, animates the polychromic view of time. In more monochromic settings, an individualist way of life is more easily accommodated. Individualists can more easily extract moments in time, and individuals themselves, from the networks around them. If time is a straight line stretching forward and not back, then fate or destiny may be less compelling. (For more on this, see the essay on Communication Tools for Understanding Cultural Difference.)

Fate and Personal Responsibility

Another important variable affecting communication across cultures is fate and personal responsibility. This refers to the degree to which we feel ourselves the masters of our lives, versus the degree to which we see ourselves as subject to things outside our control. Another way to look at this is to ask how much we see ourselves able to change and maneuver, to choose the course of our lives and relationships. Some have drawn a parallel between the emphasis on personal responsibility in North American settings and the landscape itself. The North American landscape is vast, with large spaces of unpopulated territory. The frontier mentality of “conquering” the wilderness, and the expansiveness of the land stretching huge distances, may relate to generally high levels of confidence in the ability to shape and choose our destinies.

In this expansive landscape, many children grow up with an epic sense of life, where ideas are big, and hope springs eternal. When they experience setbacks, they are encouraged to redouble their efforts, to “try, try again.” Action, efficacy, and achievement are emphasized and expected. Free will is enshrined in laws and enforced by courts.

Now consider places in the world with much smaller territory, whose history reflects repeated conquest and harsh struggles: Northern Ireland, Mexico, Israel, Palestine. In these places, there is more emphasis on destiny’s role in human life. In Mexico, there is a legacy of poverty, invasion, and territorial mutilation. Mexicans are more likely to see struggles as inevitable or unavoidable. Their fatalistic attitude is expressed in their way of responding to failure or accident by saying “no modo” (“no way” or “tough luck”), meaning that the setback was destined.

This variable is important to understanding cultural conflict. If someone invested in free will crosses paths with someone more fatalistic in orientation, miscommunication is likely. The first person may expect action and accountability. Failing to see it, they may conclude that the second is lazy, obstructionist, or dishonest. The second person will expect respect for the natural order of things. Failing to see it, they may conclude that the first is coercive or irreverent, inflated in his ideas of what can be accomplished or changed.

Face and Face-Saving

Another important cultural variable relates to face and face-saving. Face is important across cultures, yet the dynamics of face and face-saving play out differently. Face is defined in many different ways in the cross-cultural communication literature. Novinger says it is “the value or standing a person has in the eyes of others…and that it relate[s] to pride or self-respect.”[5] Others have defined it as “the negotiated public image, mutually granted each other by participants in [communication].”[6] In this broader definition, face includes ideas of status, power, courtesy, insider and outsider relations, humor, and respect. In many cultures, maintaining face is of great importance, though ideas of how to do this vary.

The starting points of individualism and communitarians are closely related to face. If I see myself as a self-determining individual, then face has to do with preserving my image with others and myself. I can and should exert control in situations to achieve this goal. I may do this by taking a competitive stance in negotiations or confronting someone who I perceive to have wronged me. I may be comfortable in a mediation where the other party and I meet face to face and frankly discuss our differences.

If I see my primary identification as a group member, then considerations about face involve my group. Direct confrontation or problem-solving with others may reflect poorly on my group, or disturb overall community harmony. I may prefer to avoid criticism of others, even when the disappointment I have concealed may come out in other, more damaging ways later. When there is conflict that cannot be avoided, I may prefer a third party who acts as a shuttle between me and the other people involved in the conflict. Since no direct confrontation takes place, face is preserved and potential damage to the relationships or networks of relationships is minimized.

Nonverbal Communication

16. Nonverbal communication is hugely important in any interaction with others; its importance is multiplied across cultures. This is because we tend to look for nonverbal cues when verbal messages are unclear or ambiguous, as they are more likely to be across cultures (especially when different languages are being used). Since nonverbal behavior arises from our cultural common sense — our ideas about what is appropriate, normal, and effective as communication in relationships — we use different systems of understanding gestures, posture, silence, special relations, emotional expression, touch, physical appearance, and other nonverbal cues. Cultures also attribute different degrees of importance to verbal and nonverbal behavior.

Low-context cultures like the United States and Canada tend to give relatively less emphasis to nonverbal communication. This does not mean that nonverbal communication does not happen, or that it is unimportant, but that people in these settings tend to place less importance on it than on the literal meanings of words themselves. In high-context settings such as Japan or Colombia, understanding the nonverbal components of communication is relatively more important to receiving the intended meaning of the communication as a whole.

Some elements of nonverbal communication are consistent across cultures. For example, research has shown that the emotions of enjoyment, anger, fear, sadness, disgust, and surprise are expressed in similar ways by people around the world. Differences surface with respect to which emotions are acceptable to display in various cultural settings, and by whom. For instance, it may be more social acceptable in some settings in the United States for women to show fear, but not anger, and for men to display anger, but not fear.[8] At the same time, interpretation of facial expressions across cultures is difficult. In China and Japan, for example, a facial expression that would be recognized around the world as conveying happiness may actually express anger or mask sadness, both of which are unacceptable to show overtly.

These differences of interpretation may lead to conflict, or escalate existing conflict. Suppose a Japanese person is explaining her absence from negotiations due to a death in her family. She may do so with a smile, based on her cultural belief that it is not appropriate to inflict the pain of grief on others. For a Westerner who understands smiles to mean friendliness and happiness, this smile may seem incongruous and even cold, under the circumstances. Even though some facial expressions may be similar across cultures, their interpretations remain culture-specific. It is important to understand something about cultural starting-points and values in order to interpret emotions expressed in cross-cultural interactions.

Another variable across cultures has to do with proxemics, or ways of relating to space. Crossing cultures, we encounter very different ideas about polite space for conversations and negotiations. North Americans tend to prefer a large amount of space, perhaps because they are surrounded by it in their homes and countryside. Europeans tend to stand more closely with each other when talking, and are accustomed to smaller personal spaces. In a comparison of North American and French children on a beach, a researcher noticed that the French children tended to stay in a relatively small space near their parents, while U.S. children ranged up and down a large area of the beach.

The difficulty with space preferences is not that they exist, but the judgments that get attached to them. If someone is accustomed to standing or sitting very close when they are talking with another, they may see the other’s attempt to create more space as evidence of coldness, condescension, or a lack of interest. Those who are accustomed to more personal space may view attempts to get closer as pushy, disrespectful, or aggressive. Neither is correct — they are simply different.

Also related to space is the degree of comfort we feel moving furniture or other objects. It is said that a German executive working in the United States became so upset with visitors to his office moving the guest chair to suit themselves that he had it bolted to the floor. Contrast this with U.S. and Canadian mediators and conflict-resolution trainers, whose first step in preparing for a meeting is not infrequently a complete rearrangement of the furniture.

Finally, line-waiting behavior and behavior in group settings like grocery stores or government offices is culturally-influenced. Novinger reports that the English and U.S. Americans are serious about standing in lines, in accordance with their beliefs in democracy and the principle of “first come, first served.” The French, on the other hand, have a practice of resquillage, or line jumping, that irritates many British and U.S. Americans. In another example, immigrants from Armenia report that it is difficult to adjust to a system of waiting in line, when their home context permitted one member of a family to save spots for several others.

These examples of differences related to nonverbal communication are only the tip of the iceberg. Careful observation, ongoing study from a variety of sources, and cultivating relationships across cultures will all help develop the cultural fluency to work effectively with nonverbal communication differences.

Skill of Negotiations – Actors

The key actors in a negotiation are the negotiators themselves. Rubin describes five attributes linked to successful negotiators . First, effective negotiators have the capacity to be flexible on the method to achieve their goals. They establish their goals early on with an idea as to the general nature of the outcome but remain flexible on the means for achieving these goals. Second, negotiators remain sensitive to “social cues” (interpersonal sensitivity) given off by their counterparts without being over-reactive to these observations. To ignore the cues may be to miss out on important pieces of data. Conversely, to react too strongly risks misinterpreting intentions based on personal bias. The third attribute is the negotiator’s “inventiveness” or ability to develop creative solutions in order to strive for mutually acceptable agreement. Patience is the successful negotiator’s fourth attribute. Rubin attaches this trait to the negotiator’s ability to look beyond immediate gains with a view on the long game. Finally, successful negotiators are tenacious especially in the area of reconfiguring an “adversarial relationship into a more collaborative arrangement” .

Cultural Effects on Negotiating Style

In a survey of 310 persons from 12 countries and 8 occupations, Salacuse asked participants to rate their negotiating style covering ten negotiation process factors. Table- 6 lists the ten negotiation factors. The countries that were represented in the survey were Spain, France, Brazil, Japan, the U.S, Germany, the U.K., Nigeria, Argentina, China, Mexico and India. The occupational specialties included law, military, engineering, diplomacy/public sector, students, accounting, teaching, and management/marketing. .

Table 6. The Impact of Culture on Negotiations

| NEGOTIATION FACTORS | CULTURAL RESPONSES |

| Goal | Contract or Relationship |

| Attitudes | Win/Lose or Win/Win |

| Personal Styles | Informal or Formal |

| Communications | Direct or Indirect |

| Time Sensitivity | High or Low |

| Emotionalism | High or Low |

| Agreement Form | Specific or General |

| AgreementBuilding | Bottom Up or Top Down |

| Team Organization | One Leader or Consensus |

| Risk-taking | High or Low |

Various cultures differed on the interpretation of what constitutes a deal. To some, the deal is the contract that will be relied upon when new situations should arise. Other culture groups view the contract as an instrument that outlines general principles versus detailed rules . According to Salacuse’s survey results, among all respondents 78% preferred a specific, detailed contract. Breaking down the responses by individual cultures indicated that a majority of the respondents also preferred specific agreements to general agreements. Salacuse attributes this occurrence to the relatively large number of lawyers contained in the overall population (about one-third) and that multinational corporations favor specific agreements and many of the respondents had experiences with these types of firms . In addition to demonstrating cultural variations with regard to negotiation styles, Salacuse’s research report also demonstrates two significant implications to practitioners. First, that cultural difference appears in different areas. As was revealed by the different responses by profession and occupation in the survey, sub-cultural considerations are also influential in the negotiation process. Second, when faced with cultural issues during negotiation, it would be beneficial to garner support from negotiators with similar professional or occupational backgrounds to help bridge cultural differences.

Developing a Strategy

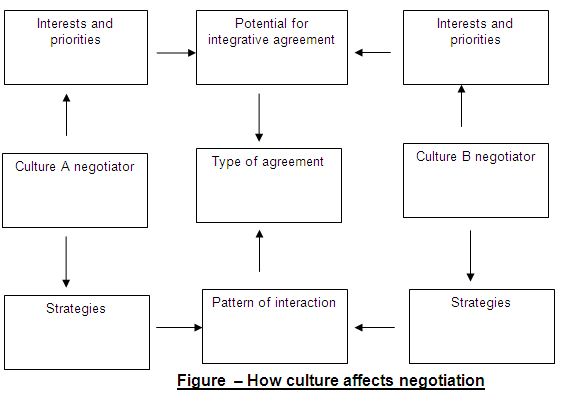

The challenge is to understand if cultural differences could be a driving influence in the course of a negotiation (and to what degree) and then developing a strategy that fits into the cultural context of the proceedings as perceived by all parties. It must be kept in mind that the joint decision very well could be to arrive at no agreement. Second, each actor in a negotiation brings to the process their own frames of reference comprised of procedural, substantive, and psychological interests. Negotiators bring to bear various skills throughout the three phases of a negotiation to assist in addressing these frames of reference (Appendix-3).

An important aspect in developing a cross-cultural negotiation strategy revolves around preparation. First, in addition to analyzing the current issue(s) that brought the parties to the table, it is advisable to study the other negotiator’s culture and history . Next, it is equally necessary that a negotiator be self-aware of his or her own cultural proclivities. This is important in order to gain insight into potential cultural similarities or differences that could come into play during the negotiations. This 360-degree cultural awareness will also facilitate in developing the strategy boundaries that will be discussed below. Finally, establishing a relationship with the other parties involved, preferably before the negotiations begin is “time well spent” . The intent would be to provide the negotiators with an opportunity to find a common basis on which to build a relationship or what Salacuse describes as a “bridging technique” . The negotiator’s skills in research, preparing the environment, building rapport, and educating on needs and perspective in the cultural context will impact the various interests associated with the three of the frames of reference as depicted in Appendix-3. Gaining an understanding of how a particular culture approaches its procedural interest is excellent information to have. For example, the establishment of goals in the negotiation may be different to a low MAS culture where relationships are important versus a high MAS culture where material success and progress are valued. Another example would be in the area of role definitions. A cross-cultural negotiator’s interactions with his counterpart could be influenced with the understanding that, in general, inequalities among people are expected and desired in a high PDI culture. Knowledge gained concerning a culture’s various substantive interests is also significant to the cross-cultural negotiator. For example, in a high UAI culture, those that generally exhibit a low tolerance for ambiguity, precise information (and the more the better) is an important commodity with which to meet at least one element of their substantive interests.

The choice of a particular negotiation strategy is obviously more complicated than simply deciding which approach best fits a particular negotiator’s individual style; the other party gets a vote in the process as well. In addition, a negotiator may find themselves in a position where their initial strategy needs to be adjusted as the negotiation process continues through the various phases. A generalized understanding of the other party’s culture is a valuable starting point. Recognizing when cultural influences, especially as they relate to values and trust, are affecting the negotiation process requires careful attention to the environmental situation. The degree of flexibility that a negotiator can bring to bear on the situation is also an important function in the negotiation process. It is the negotiator’s ability and /or willingness to adapt to cultural differences that will determine the enabling characteristics (strategy) that can be utilized to facilitate the process.

How Cross Culture Negotiation Implemented:

Understand expectations

Your negotiating partner’s expectations of the negotiation may well be very different from yours. Like you, he will want to succeed, but success may not mean the same thing to him and his co-nationals as it does to you.

Decision-making styles may be different, too. American managers usually make decisions by themselves, while Japanese managers tend to make decisions by consensus, a practice that can add time to the negotiation process. Americans place a high value on flexibility, whereas once a Japanese manager has reached a decision, he believes it is shameful to change it, says Tokyo-based management consultant Mitsugu Iwashita, director of the Intercultural and Business Communication Center. Understanding these underlying attitudes helps you see what your potential partner’s priorities are, and you can then adapt your strategy accordingly.

Establish common ground and choose your style

Find anything that will allow your foreign colleague to share something with you. This can help you get past “people” problems—ego wars, saving face, and so on—which is a good tactic because these problems can crop up where you may least expect them.

Now the real work can begin. You’ll need to choose which of two classic negotiating styles you’ll adopt: Contentious or problem-solving. The contentious negotiator, a tough, demanding guy who makes few compromises, can be a great success given the right conditions. He either wins or loses, but never comes to a conditional agreement. The problem-solving negotiator takes a broader view, attempting to get as much as she can without handing out a deal breaker. She establishes common ground wherever she can find it and approaches negotiations on a step-by-step basis.

While one has to be careful about generalizing across cultures, experts agree that a problem-solving approach to cross-cultural negotiations is prudent. (Indeed, many would say it’s the right choice for almost any negotiation.) The problem-solving approach helps to avoid blunders, says Elaine Winters, coauthor of Cultural Issues in Business Communication (Program Facilitating and Consulting, 2000). But there are limits to this approach. In many cultures, negotiation is ritualized, especially in its early stages. It is obviously important to learn these negotiating rituals for a given culture, even if your foreign partner turns out not to require them. Germans, for example, often need to spend a large part of the initial negotiations in number crunching. All the facts and figures must be agreed upon, and woe betide the negotiator who makes a mistake! This German trait is not really about number crunching, however; it is a confidence-building ritual in which two potential partners run through a series of routine checks just to display trustworthiness. So the problem-solving approach, which would try to find common ground quickly, could prove threatening for the ritual negotiators.

“When confronted with cultural differences in negotiating styles, we need to be aware of the potentially adverse effects of a flexible, mixed style,” says Willem Mastenbroek, director of the Holland Consulting Group (Amsterdam) and professor of organizational culture and communication at the Free University of Amsterdam. “If it is not understood, people may perceive it as smooth and suave behavior and resent it. Because they are not able to counter it with equal flexibility, they may feel clumsy and awkward, in some way even inferior. It may also become difficult for them to believe in the sincerity of the other side. They may see it as an effort to lure them into a game defined by established groups which will put them at a disadvantage.”

Manage the Negotiation

Let’s assume that you have passed successfully through the initial stages of the negotiation and that you have agreed upon common ground with your prospective partner. The game of tactics now broadens. It is at this stage, in which the actual issues go back and forth between participants, that your awareness of negotiating behavior typical to your potential partner’s culture can be put to use.

Italian negotiators, for example, will often try to push through this stage quite quickly, repeatedly insisting on their terms to tire out their opponents. Knowing this, a foreign negotiator may find a good tactic is to display no great hurry to deal—change the subject, digress, etc.

On the other hand, Chinese negotiators usually make one offer after another at this point to test the limits of a possible deal. According to Winters, nonverbal communication in negotiations with a Chinese businessman can be quite important. He may say little in response to your questions, and expect you to garner what you need to know from his gestures and from the context of whatever he does say. More demonstrative Western cultures can find this conduct very difficult to work with, but the application here of patience and deductive reasoning can take you a long way.

Most Europeans won’t break off discussions unless they are deeply offended, but Asian negotiators are often happy to drop the project if they are uncomfortable with some aspect of the negotiations. If this happens, try to backtrack and fix the problem.

But in focusing on your potential partner’s culture, don’t lose sight of him as an individual. It’s always best to learn as much as you can about his personality and communication style. “Personalize negotiation methods and approaches,” Winters says. “Don’t ignore culture (impossible anyway!), try to treat it as background; focus on the capabilities of the specific individuals at the table. This is frequently successful because a new, mutually agreed-upon culture is being created just for this effort.

Conclusion:

It is known that cultural values create differences in negotiating norms. Therefore, it is helpful to know and understand the connection between the culture and the negotiation strategies of the other party. Western culture concerns itself primarily with the needs and goals of the individual. Autonomy is highly regarded and protected in society. Unlike collectivism, self identity is not dependent on the characteristics of a larger group. As we have explained, members of an individualistic society tend to set higher personal goals in the negotiation process. They also have a tendency to reject less favorable 15 outcomes in the negotiation process. These outcomes may indeed be acceptable, ho waver the search will continue until a solution is found that most suits the individuals needs. Members of a collectivist society base their identity on the characteristics of the group to which they belong. We have stated that members of a collectivist society are more sensitive to the needs of others and they approach the negotiation process with the needs of the group in mind. When members of this group negotiate, they are most cooperative when negotiating with members of a like group. They tend to become more competitive when negotiating with those of different groups.

We also discussed egalitarianism vs. hierarchy. In hierarchal societies social status implies power. Having a hierarchal structure reduces conflict by providing a norm and people do not normally venture outside the norm. As a positive, members of a hierarchal society are required to look out for those that are socially inferior to them, which is quite the opposite in an egalitarian society. Egalitarianism encourages resolution of conflict on one’s own personal and social boundaries are permeable.

In the negotiation process, information is highly valued and communication style plays a major role in the outcome of intercultural communication. As we explained high context communication in which meaning is inferred and relies on preexisting knowledge can cause conflict when met with the needs of low-context communication that requires clear and precise detail. Important information may not be exchanged and an optimal solution may not be reached.

The Culture as Shared Values theory is based on the differences between cultures and their values and how it results in different negotiating techniques especially between individualistic and collectivistic cultures. Collectivistic cultures tend to be more integrative, less competitive, and have greater information exchange. There are, however, deviations from the norm, and culture does not necessarily determine how one will go about negotiating.

The Culture in Context theory treats culture as but one element in a complexity of negotiator behavior. Sometimes, differences in integrative and distributive bargaining preferences may have to do more with contextual factors as opposed to where one is on the individual-collective continuum. It has been shown that integrative bargaining is more beneficial to sellers and distributive bargaining is more beneficial to buyers. In addition, individualism-collectivism is not necessarily the only link to how a negotiator preconceives competitiveness in negotiation. Although individualism-collectivism is known as an 16 indicator of mythical fixed pie beliefs: Buyer-seller roles can sometimes be a better predictor of mythical fixed pie beliefs.

We would like to conclude with the assurance that despite cultural differences, optimal results in the negation process can still be achieved. There are three key elements for success: parties to a negotiation must value the sharing of information, there must be a means to search for information, and finally, both parties in the negotiation process must be willing to search for the information. When exercising these three key factors, both parties should be able to walk away with acceptable outcomes.