Mucosal vaccines, which are administered through the nose or mouth, have the potential to provide protection against respiratory viruses by stimulating an immune response in the mucosal lining of the respiratory tract. These vaccines are designed to mimic the natural route of infection for respiratory viruses, which typically enter the body through the nasal or oral mucosa.

There are several different types of mucosal vaccines being developed for respiratory viruses, including live attenuated vaccines, inactivated vaccines, and subunit vaccines. Live attenuated vaccines use a weakened form of the virus to stimulate an immune response, while inactivated vaccines use a killed version of the virus. Subunit vaccines use only a part of the virus, such as a protein or a viral antigen, to stimulate an immune response.

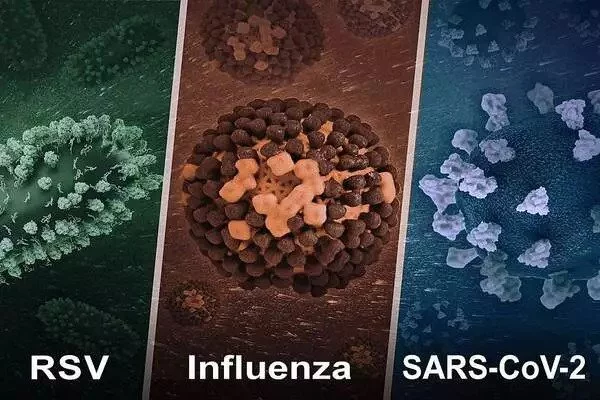

Vaccines that provide long-lasting protection against influenza, coronaviruses, and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) have proved exceptionally difficult to develop. In a new review article in Cell Host & Microbe, researchers from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), part of the NIH, explore the challenges and outline approaches to improved vaccines. Anthony S. Fauci, M.D., former NIAID director, is an author along with Jeffery K. Taubenberger, M.D., Ph.D., and David M. Morens, M.D.

To develop useful mucosal vaccines, significant knowledge gaps must be filled including finding ideal vaccine formulations; determining dosage size, frequency, and timing; and developing techniques for overcoming immune tolerance.

Unlike the respiratory viruses that cause measles, mumps, and rubella – for which vaccination or recovery from illness provides decades-long protection against future infection – flu, RSV, SARS-CoV-2, and “common cold” coronaviruses share several characteristics that enable them to cause repeated re-infections. These include very short incubation periods, rapid host-to-host transmission, and replication in the nasal mucosa rather than throughout the body. This last feature – non-systemic replication – means these viruses do not stimulate the full force of the adaptive immune response, which typically takes a week or more to mount.

A next generation of improved vaccines for mucosa-replicating viruses will require advances in understanding on several fronts, the authors say. For instance, more must be learned about interactions between flu viruses, coronaviruses, and RSV and the components of the immune response that operate largely or exclusively in the upper respiratory system. Over time, these interactions have evolved and led to “immune tolerance,” wherein the human host tolerates transient, limited infections by viruses that are generally non-lethal to avoid the destructive consequences of an all-out immune system attack.

The authors note that mucosal immunization appears to be an optimal route of vaccination for the viruses of interest, when feasible. However, to develop useful mucosal vaccines, significant knowledge gaps must be filled including finding ideal vaccine formulations; determining dosage size, frequency, and timing; and developing techniques for overcoming immune tolerance.

The NIAID authors urge fellow researchers to “think outside the box” to make strides toward vaccines that can elicit durable protection against these viruses of considerable public health impact. They conclude, “we are excited and invigorated that many investigators…are rethinking, from the ground up, all of our past assumptions and approaches to preventing important respiratory viral diseases and working to find bold new paths forward.”

Mucosal vaccines for respiratory viruses are still in the early stages of development and testing. However, some promising results have been seen in animal studies and human clinical trials. For example, in a phase 2 clinical trial, a live attenuated vaccine for RSV (Respiratory Syncytial Virus) showed significant protection against infection. It’s important to note that while mucosal vaccines are under development, it’s still important to follow the currently recommended vaccines and guidelines for protection against respiratory viruses.