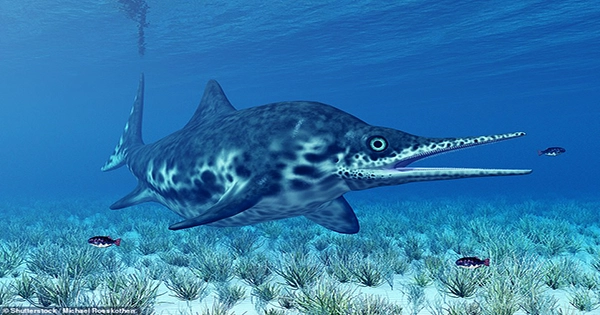

During March and April of this year, ancient riches spilled out of a glacier in Patagonia, including Chile’s first complete ichthyosaur specimen. “Fiona” is one of a group of 23 prehistoric reptiles discovered in the area, and she comes with many embryos. The Early Cretaceous fossilized remains, believed to be between 129 and 139 million years old, were discovered under melting ice in the Tyndall Glacier area of Chilean Patagonia by a team led by The University of Magallanes (UMAG). The remains were able to be securely wrapped and transported via helicopter since they were located within the Torres del Paine National Park.

In a statement, Dr. Judith Pardo-Pérez, the first female paleontologist to conduct an expedition of this scale in Patagonia, said, “The results of the trip fulfilled all expectations, and even more than predicted.” It’s a good thing, too, because finding, extracting, and meticulously wrapping the amazing and delicate fossil remains took 31 days. Fiona, the sole known fossil of a pregnant female ichthyosaur from the Valanginian-Hauterivian period, was rewarded for their efforts by the melting glacier.

A team led by paleontological excavator Héctor Ortiz of the Chilean Antarctic Institute and the University of Chile and paleontological technician Jonatan Kaluza of Fundación de Historia Natural Félix de Azara and CONICET uncovered the first-of-its-kind fossil. “At 4 meters [13 feet] long, complete, and with embryos in gestation,” Pardo-Pérez stated, “the excavation will assist to reveal knowledge on its species, the palaeobiology of embryonic development, and a sickness that plagued it during its lifespan.”

Fiona, together with her 23 ichthyosaur buddies, is said to be the world’s best early Cretaceous ichthyosaur deposit, because to its amazing collection of remarkably well-preserved fossilized bones. The fossils will now help researchers learn more about these ancient species, their features, and how they lived. “We hope to get results on the diversity, disparity, and palaeobiology of the ichthyosaurs of the Tyndall Glacier locality, establish degrees of bone maturity and ecological niches to evaluate possible dietary transitions that occurred throughout their evolution, and help establish palaeobiogeographical connections with ichthyosaurs from other latitudes,” Pardo-Pérez said.

As a fellow paleontologist and “Visiting Scientist” linked with The University of Manchester, Dr Dean Lomax – who readers may recall from the Rutland ichthyosaur, which he regarded as “one of the finest discovery in British palaeontological history” – was also present for the voyage. He unearthed a handful of the riches as part of the collaborative team behind the spate of discoveries, including a juvenile ichthyosaur’s skull, which is regarded to be the best-preserved specimen of its species recovered to date. “The large number of ichthyosaurs discovered in the region, included entire bones of adults, juveniles, and newborns,” he stated. “The worldwide partnership makes it possible to share this extraordinary ichthyosaur cemetery with the rest of the world and, to a considerable extent, to advance research.”