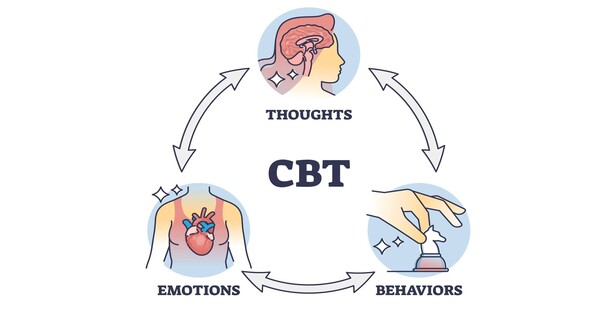

Cognitive behavioral therapy, one of the most common treatments for depression, can educate people how to cope with everyday problems, reinforce positive behaviors, and combat negative ideas. Can changing one’s ideas and behaviors cause long-term changes in the brain?

Stanford Medicine-led research has discovered that it is possible if a medicine is matched with the proper people. In a study of people with depression and obesity, a difficult-to-treat combination, cognitive behavioral therapy with a focus on problem solving improved depression in one-third of participants. These patients also shown adaptative alterations in their brain circuitry.

Furthermore, these brain modifications were detectable after only two months of therapy and might predict which patients would benefit from long-term treatment. The findings add to evidence that selecting treatments based on the neurological roots of a patient’s depression, which differ from person to person, improves the chances of success.

The similar principle is already widely used in other medical fields.

If you had chest pain, your physician would suggest some tests – an electrocardiogram, a heart scan, maybe a blood test – to work out the cause and which treatments to consider.

Leanne Williams

“If you had chest pain, your physician would suggest some tests – an electrocardiogram, a heart scan, maybe a blood test – to work out the cause and which treatments to consider,” said Leanne Williams, PhD, the Vincent V.C. Woo Professor, a professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences, and the director of Stanford Medicine’s Center for Precision Mental Health and Wellness.

“Yet in depression, we have no tests being used. You have this broad sense of emotional pain, but it’s a trial-and-error process to choose a treatment, because we have no tests for what is going on in the brain.”

Williams and Jun Ma, MD, PhD, professor of academic medicine and geriatrics at the University of Illinois at Chicago, are co-senior authors of the study published in Science Translational Medicine. The work is part of a larger clinical trial called RAINBOW (Research Aimed at Improving Both Mood and Weight).

Problem solving

The trial used a type of cognitive behavioral treatment known as problem-solving therapy, which is intended to improve cognitive skills used in planning, troubleshooting, and blocking out irrelevant information. A therapist helps patients identify real-life problems, such as a fight with a roommate, brainstorm solutions, and choose the best one.

These cognitive abilities rely on a specific group of neurons that work together, known as the cognitive control circuit. Previous research from Williams’ team, which established six biotypes of depression based on brain activity patterns, suggested that one-quarter of persons with depression have malfunction in their cognitive control circuits, either too much or too little.

The current study included adults who had been diagnosed with both significant depression and obesity, a combination of symptoms that frequently implies difficulties with the cognitive control circuit. Patients with this profile perform poorly on antidepressants, with a response rate of only 17%.

Of the 108 participants, 59 completed a year-long program of problem-solving therapy in addition to their usual care, which included drugs and visits to their primary care physician. The remaining 49 received merely routine care.

They were given fMRI brain scans at the beginning of the study, then after two months, six months, 12 months and 24 months. During the brain scans, the participants completed a test that involves pressing or not pressing a button according to text on a screen — a task known to engage the cognitive control circuit. The test allowed the researchers to gauge changes in the activity of that circuit throughout the study.

“We wanted to see whether this problem-solving therapy in particular could modulate the cognitive control circuit,” said Xue Zhang, PhD, a postdoctoral scholar in psychiatry who is the lead author of the study. With each brain scan, participants also filled out standard questionnaires that assessed their problem-solving ability and depression symptoms.

Working smarter

Problem-solving therapy, like other forms of depression treatment, did not work for everyone. However, 32% of patients responded to the therapy, indicating that their symptom severity dropped by half or more.

“That’s a huge improvement over the 17% response rate for antidepressants,” Zhang informed us.

When the researchers reviewed the brain scans, they discovered that in the group receiving only standard care, a cognitive control circuit that became less active over the course of the trial was associated with deteriorating problem-solving abilities. However, in the group undergoing therapy, the pattern was reversed: decreased activity was associated with improved problem-solving abilities. The researchers believe this is because the therapy taught their brains how to handle information more efficiently.

“We believe they have more efficient cognitive processing, meaning now they need fewer resources in the cognitive control circuit to do the same behavior,” Zhang said.

Before the therapy, their brains had been working harder; now, they were working smarter. Both groups, on average, improved in their overall depression severity. But when Zhang dug deeper into the 20-item depression assessment, she found that the depression symptom most relevant to cognitive control — “feeling everything is an effort” — benefited from the more efficient cognitive processing gained from the therapy.

“We’re seeing that we can pinpoint the improvement specific to the cognitive aspect of depression, which is what drives disability because it has the biggest impact on real-world functioning,” Williams said.

Indeed, some participants reported that problem-solving therapy helped them think more clearly, allowing them to return to work, resume hobbies and manage social interactions.

Fast track to recovery

Only two months into the trial, brain scans revealed alterations in cognitive control circuit activity in the therapy group.

“That’s important, because it tells us that there is an actual brain change going on early, and it’s in the time frame that you’d expect brain plasticity,” according to Williams. “Real-world problem solving is literally changing the brain in a couple of months.”

The idea that ideas and behaviors can change brain circuits is similar to how exercise, a behavior, builds muscles, she explained.

The researchers discovered that these early changes indicated which individuals were responding to the therapy and were likely to improve their problem-solving skills and depression symptoms six months, 12 months, and even one year later, at 24 months. That means a brain scan might be used to determine which people are best suited for problem-solving therapy.

It’s a step closer to Williams’ vision of precision psychiatry, which involves studying brain activity to match patients with medicines that are most likely to help them, so accelerating their recovery.

“It’s definitely advancing the science,” Zhang added. “But it’s also going to transform a lot of people’s lives.”