According to a new UBC study, climate change will compel 45 percent of fish stocks that straddle two or more exclusive economic zones to shift dramatically from their historical habitats and migration pathways by 2100, posing a challenge that could lead to international conflict.

By 2030, when the UN Sustainable Development Goals are expected to be met, 23% of these ‘transboundary’ fish species will have shifted their historical habitat range. According to the modeling study, at least one moving fish stock will occur in 78% of exclusive economic zones (EEZs) where most fishing occurs.

If nothing is done to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, this rises to 45% of stocks by 2100, with 81 percent of EEZs experiencing at least one stock movement.

“This is not only an issue of stocks leaving or arriving to new EEZs, but of stocks that are shared between countries, completely changing their dynamics,” said lead author Dr. Juliano Palacios-Abrantes, who conducted the study while at UBC’s Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries (IOF).

He’s now a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and he says the study gives a timeline that shows these transformations have been happening since the dawn of the twenty-first century.

“We will see even more dramatic changes by 2030 and onwards, given current emissions rates. Many of the fisheries management agreements made to regulate shared stocks were established in past decades, with rules that apply to a world situation that is not the same as today.”

This is not only an issue of stocks leaving or arriving to new EEZs, but of stocks that are shared between countries, completely changing their dynamics. We will see even more dramatic changes by 2030 and onwards, given current emissions rates. Many of the fisheries management agreements made to regulate shared stocks were established in past decades, with rules that apply to a world situation that is not the same as today.

Dr. Juliano Palacios-Abrantes

Starting in 2006 and projected to 2100, the study examined the shifting ranges of 9,132 transboundary fish species, which account for 80% of the catch taken from the world’s EEZs.

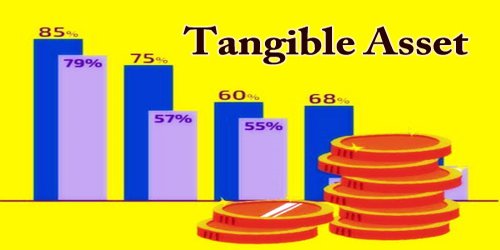

Changes in the distribution of stocks will have an impact on catches. By 2030, 85% of the world’s EEZs will have experienced a change in the volume of transboundary catch that is greater than usual yearly volatility.

Dr. Palacios-Abrantes expects this trend to increase disputes over which nations can claim majority ownership of specific stocks, especially given that transboundary species fishing generated an estimated US$76 billion in revenue between 2005 and 2010.

A shift in the distribution of numerous salmon stocks upset fishing agreements between Canada and the United States in the 1980s and 1990s, contributing to overfishing concerns in these species. Such conflicts will be magnified in the future, and may collapse international agreements, Dr. Palacios-Abrantes said.

As sea temperatures rise, countries in tropical areas such as the Caribbean and South Asia will be the first to be affected, but northern countries will also be affected. By 2033, ten common stocks in Canada and the United States Pacific are expected to move.

“By providing estimates of the size and timing of projected shifts, our study offers tangible reference points around which to consider climate change impacts and negotiate fair policies for sustainable management”, said co-author Dr. Colette Wabnitz (she/her), lead scientist at Stanford’s Center for Ocean Solutions and IOF research associate.

The research offers a variety of recommendations for avoiding the worst consequences of future conflicts, including drafting agreements that enable fishing fleets to fish in neighboring countries’ waters in exchange for a piece of the catch or profit.

It will also necessitate adjusting and renegotiating many of the existing catch quota agreements. According to the authors, any action taken to mitigate climate change should aid in reducing expected shifts.

“We must accept that climate change is happening, and then move fast enough to adapt fisheries management regulations to account for it,” said co-author Dr. Gabriel Reygondeau, a research associate at IOF.

This means that governments must be willing to collaborate in order to avoid potential conflict as a result of species climate change and to maintain the sector profitable and sustainable, according to him.

“We evaluated where the potential shift and conflict could emerge and when it’s going to happen following climate models and scenarios. At some point, scientists cannot help more and the question becomes: does politics want to deal with climate change effects on primary resources and production now?”