Many people believe that children learn better than adults. The idea is that children are less afraid to take risks because they have fewer responsibilities and are less vulnerable to mistakes. The environment of a child is a significant motivator in their learning. They are at school studying a variety of subjects, participating in various sports, and participating in various extracurricular activities. Adults, on the other hand, are usually focused on one subject and are less open to different learning opportunities in their lives.

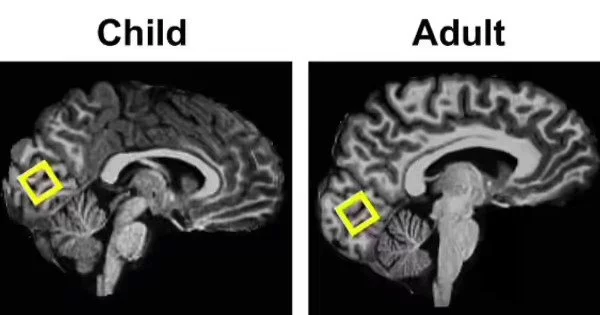

If you’ve ever thought your elementary school kids were “smarter” than you – or at least faster at picking up new information and skills – a new study published in Current Biology on November 15 suggests you’re right. The new study also offers a reason: kids and adults exhibit differences in a brain messenger known as GABA, which stabilizes newly learned material.

“Our findings show that children of elementary school age can learn more items in a given period of time than adults, making learning more efficient in children,” said Brown University’s Takeo Watanabe.

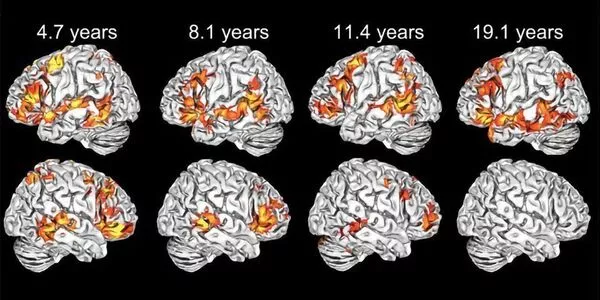

Their findings revealed that children experience a rapid increase in GABA during visual training that lasts after the training is completed. This is in stark contrast to adult GABA concentrations, which remained constant. The findings suggest that children’s brains respond to training in a way that allows them to stabilize new learning more quickly and efficiently.

Our findings show that children of elementary school age can learn more items in a given period of time than adults, making learning more efficient in children. It is commonly assumed that children learn more efficiently than adults, but scientific support for this assumption has been, at best, weak, and, if true, the neuronal mechanisms responsible for more efficient learning in children are unknown.

Takeo Watanabe

“It is commonly assumed that children learn more efficiently than adults, but scientific support for this assumption has been, at best, weak, and, if true, the neuronal mechanisms responsible for more efficient learning in children are unknown,” Watanabe said.

Differences in GABA were one obvious place to look for answers. While previous studies had done so, the researchers noted that GABA in children had only been measured at one-time point. It was also not measured at a time when there was any special significance in terms of learning. So, in the new study, they set out to see how GABA levels change before, during, and after learning. They also wanted to see how that differed between children and adults.

The study examined visual learning in elementary school-age children and adults using behavioral and state-of-the-art neuroimaging techniques. It found that visual learning triggered an increase of GABA in children’s visual cortex, the brain area that processes visual information. That GABA boost also persisted for several minutes after training ended.

What they saw in adults that were offered the same visual training was notably different. In adults, there were no changes in GABA whatsoever. The discovery predicts that training on new items rapidly increases the concentration of GABA in children and allows learning to be rapidly stabilized. Further experiments also supported this.

“In subsequent behavioral experiments, we discovered that children stabilized new learning much faster than adults, which agrees with the widely held belief that children outperform adults in their learning abilities,” says Sebastian M. Frank, now at the University of Regensburg in Germany. “Our findings point to GABA as a key player in improving learning efficiency in children.”

According to the findings, children are more likely than adults to acquire new knowledge and skills. It should provide additional motivation for teachers and parents to provide children with numerous opportunities to learn new skills, such as learning their time’s tables or riding a bike.

The findings also may change neuroscientists’ conception of brain maturity in children.

“Our results imply that children exhibit highly efficient inhibitory, GABAergic processing in spite of inhibitory failures that have been observed in other domains such as cognitive control or attention,” Frank said. “This implies that GABAergic processing involved in different aspects of cognitive function might mature at different speeds.”

“Although children’s brains are not yet fully matured, and many of their behavioral and cognitive functions are not as efficient as in adults,” Watanabe continued, “children are not, in general, outperformed in their abilities by adults.” “On the contrary, children’s abilities are superior to adults in some domains, such as visual learning.”

They believe that such differences in maturation rates between brain regions and functions should be investigated further in future research. They also want to look into GABA responses in other types of learning, like reading and writing.