Researchers at the University of Oklahoma recently published a study demonstrating that numerous brain parameters, including blood flow and the brain’s ability to compensate for a lack thereof, are stronger predictors of moderate cognitive impairment than risk factors such as hypertension and high cholesterol.

The findings improve the potential for preventing or treating memory disorders before they advance to dementia. The need is simply getting stronger. Approximately 18% of the global population has mild cognitive impairment, and 10-15% will develop dementia. By 2050, dementia is expected to afflict 152 million people.

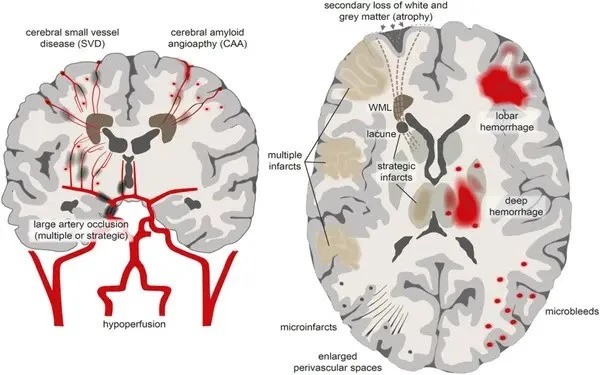

The research was led by a multidisciplinary group of researchers in the OU College of Medicine and published in Alzheimer’s & Dementia, a journal of the Alzheimer’s Association. Their studies centered on the brain’s vasculature — its network of blood vessels — and how this acts differently in older adults with mild cognitive impairment.

Every brain is different, and there may be differing reasons for cognitive impairment, but having these predictors – measuring neurovascular coupling, functional connectivity, and CEEVs – potentially opens opportunities to develop individualized interventions, whether it’s a pharmacological therapy or non-invasive brain stimulation, or something as simple as cognitive behavioral therapy.

Andriy Yabluchanskiy

“People with mild cognitive impairment are at highest risk for the next step, which is dementia,” said Calin Prodan, M.D., a professor of neurology in the OU College of Medicine and a co-author of the paper. “We’re trying to decipher the ‘fingerprints’ of mild cognitive impairment — what happens to the brain when a person moves from healthy aging to mild cognitive impairment, and is there something we can do to intervene and prevent the decline to dementia?”

The researchers collected several sorts of brain measurements from patients at three periods of life: young adults, older adults with aging but healthy brains, and older adults with slight cognitive impairment. Each group played a short memory challenge game on a computer while wearing what appeared to be a swim cap with light sensors; the technology, known as functional near-infrared spectroscopy, measured blood flow in the brain as participants were challenged to memorize increasingly long letter sequences.

In the brains of young adults, blood flow increased, giving their brains the energy they needed to meet the demands of the game, a process called neurovascular coupling. In people with healthy aging brains, the blood flow did not increase as much, but to compensate, their brains engaged other regions of the brain to help with the challenge, a process known as functional connectivity. In the brains of older adults with mild cognitive impairment, the blood flow was greatly reduced, and they lost the ability to compensate by recruiting other parts of the brain to help.

“People with mild cognitive impairment have lost that compensation mechanism. There is a drastic change in brain activity in those with mild cognitive impairment,” said Cameron Owens, Ph.D., lead author of the study. After earning his doctorate, Owens is now in his third year of medical school as part of the OU College of Medicine’s M.D./Ph.D. degree program.

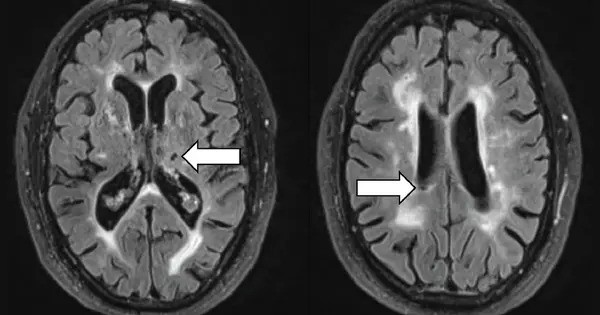

Another sort of examination, a liquid biopsy, provided researchers with an extra insight into the brains of persons with cognitive impairment. This blood test counted the number of cerebrovascular endothelial extracellular vesicles, or CEEVs, which are small particles secreted by cells lining the brain’s blood channels. Existing research indicates that when the inner lining of blood vessels is injured, it secretes CEEVS. People with minor cognitive impairment had higher levels of CEEVs in their brains than those with healthy, aging brains. Furthermore, MRI pictures revealed that those with greater levels of CEEVs had more ischemia damage, indicating that the tiny capillaries in their brains did not receive adequate blood flow. The researchers believe this is the first time CEEVs have been measured in a cognitive setting.

“Every brain is different, and there may be differing reasons for cognitive impairment, but having these predictors — measuring neurovascular coupling, functional connectivity, and CEEVs — potentially opens opportunities to develop individualized interventions, whether it’s a pharmacological therapy or non-invasive brain stimulation, or something as simple as cognitive behavioral therapy,” said Andriy Yabluchanskiy, Ph.D., OU College of Medicine associate professor of neurosurgery and co-author of the study.

The investigation will continue with various new aspects. The team intends to conduct additional research on CEEVs, which are similar to bubbles that carry a range of things, to determine whether their cargo also contributes to moderate cognitive impairment. Furthermore, because the trial began during the COVID-19 pandemic, researchers are investigating whether viral infection accelerated the progression of dementia in persons with mild cognitive impairment.