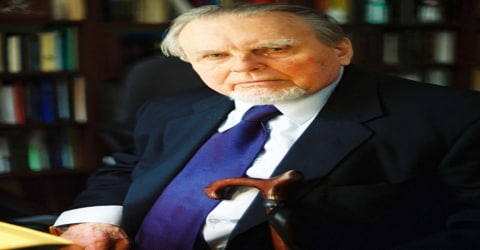

Biography of Czeslaw Milosz

Czeslaw Milosz – Polish poet, prose writer, translator, and diplomat.

Name: Czeslaw Milosz

Date of Birth: 30 June 1911

Place of Birth: Szetejnie, Kovno Governorate, Russian Empire

Date of Death: 14 August 2004 (aged 93)

Place of Death: Kraków, Poland

Occupation: Poet, prose writer, essayist

Father: Aleksander Milosz

Mother: Weronika Milosz

Spouse/Ex: Carol Thigpen (m. 1992–2002), Janina Miłosz (m. 1944–1986)

Children: John Peter Milosz, Anthony Milosz

Early Life

Czeslaw Milosz was a renowned Polish poet, novelist, essayist and translator, who was born on June 30, 1911, Šateiniai, Lithuania, Russian Empire (now in Lithuania). He always identified strongly as well with Lithuania, as he was born in what is now Kaunas County, grew up in rural Lithuania, and was educated at university in the city of Vilnius which at the time was in northeastern Poland.

He has influenced the young generation towards the turn of the 20th century through his pre-war and wartime collections. He regarded himself as a Polish poet, simply because it was his native mother tongue and he chose to compose his creations in Polish, despite the fact that he was born in Lithuania and not Poland. While he authored all his prose, poetry and essay collections in Polish language, he also exhibited his caliber in translation, which included the Polish version of ‘Psalms’ from Greek and Hebrew, apart from translated works of numerous eminent authors into Polish, namely, William Shakespeare, T.S. Eliot, Walt Whitman, and Charles Baudelaire.

His World War II-era sequence The World is a collection of twenty “naïve” poems. Following the war, he served as Polish cultural attaché in Paris and Washington, D.C., and in 1951 defected to the West. His nonfiction book The Captive Mind (1953) became a classic of anti-Stalinism. From 1961 to 1998 he was a professor of Slavic Languages and Literatures at the University of California, Berkeley.

One of the most eminent poets to emerge from Eastern Europe’s troubled twentieth-century landscape, Czeslaw Milosz (pronounced CHESS-wahf MEE-wosh) fled Poland as Soviet-style communism took root there, but returned as a literary legend as he neared his eightieth birthday. Milosz’s astounding output, which included volumes of verse, essays, and criticism, mark him as one of his country’s most prolific chroniclers of its tragic but ultimately triumphant modern era, but the quality of his work made him one of Poland’s rare Nobel Prize recipients in literature, which he was awarded in 1980.

Czeslaw Milosz became a U.S. citizen in 1970. In 1978 he was awarded the Neustadt International Prize for Literature and in 1980 the Nobel Prize in Literature for his poetry, essays and other writing. In 1999 he was named a Puterbaugh Fellow. After the fall of the Iron Curtain, he divided his time between Berkeley, California, and Kraków, Poland.

Moreover, his works have been translated into over 42 languages, by various poets, such as Robert Hass, Robert Pinsky, and Peter Dale Scott. His most notable works are ‘Zniewolony umysl’ (The Captive Mind, 1953), ‘Zdobycie wladzy’ (The Seizure of Power, 1955), ‘Traktat poetycki’ (A Poetical Treatise, 1957), and ‘Rodzinna Europa’ (Native Realm: A Search for Self Definition, 1959).

Childhood, Family and Educational Life

Czesław Miłosz was born on June 30, 1911, in the village of Szetejnie (Lithuanian: Šeteniai), Kovno Governorate, Russian Empire (now Kėdainiai district, Kaunas County, Lithuania) on the border between two Lithuanian historical regions, Samogitia and Aukštaitija, in central Lithuania. He was the son of Aleksander Miłosz (died 1959), a Polish civil engineer of Lithuanian origin, and Weronika (née Kunat; 1887-1945), a descendant of the Syruć noble family (her grandfather was Szymon Syruć).

He spent his early years traveling across Russia with his father, who served in the Czar’s army during World War I. After returning to Lithuania in 1918, the family settled in the then Polish Lithuanian capital, Wilno (now Vilnius), where his formal schooling commenced.

Miłosz became fluent in Polish, Lithuanian, Russian, English, and French. He was raised Catholic in rural Lithuania. He has emphasized his identification with the multi-ethnic Grand Duchy of Lithuania in his writings, a stance that led to ongoing controversies. He refused to identify exclusively as either a Pole or a Lithuanian. He said of himself: “I am a Lithuanian to whom it was not given to be a Lithuanian”, and “My family in the sixteenth century already spoke Polish, just as many families in Finland spoke Swedish and in Ireland English, so I am a Polish, not a Lithuanian poet. But the landscapes and perhaps the spirits of Lithuania have never abandoned me”.

Miłosz completed his secondary schooling from Sigismund Augustus Gymnasium in 1929 and graduated from Stefan Batory University with a law degree in 1931. He received a Masters degree in law from Stefan Batory University in 1934 after which he went to Paris on a one-year fellowship sponsored by the National Cultural Fund.

He began writing poetry in his teens, and was fascinated by the sciences as well; he spurned both of these to study law but won a scholarship to study literature in Paris thanks to a distant relative, Oscar Milosz, a respected poet.

Miłosz memorialized his Lithuanian childhood in a 1955 novel The Issa Valley and in the 1959 memoir Native Realm. He employed a Lithuanian-language tutor late in life to improve the skills acquired in his childhood. He said that it might be the language spoken in heaven.

Personal Life

Czesław Miłosz married Janina Dluska in 1944, with whom he fathered two sons – Anthony (1947) and John Peter (1951). Janina died from Alzheimer’s disease in 1986.

In 1992, he re-married Carol Thigpen, a US-born historian and associate dean at Emory University, Atlanta. She died in 2002.

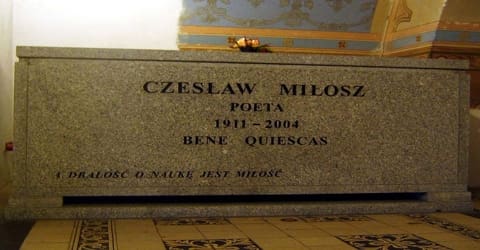

He was interred at the ancient Skalka Roman Catholic Church, Krakow, in the presence of thousands of his admirers, including prominent figures from the Polish cultural and political life. His works have been translated into several languages by various popular translators, such as Peter Dale Scott, Robert Hass, Jane Zielonko, and Robert Pinsky.

Career and Works

In 1931, Miłosz established the Polish avant-garde poetic group ‘Zagary’, along with other poets, namely, Aleksander Rymkiewicz, Jozef Maslinski, Jerzy Zagorski, Teodor Bujnicki, and Jerzy Putrament.

The son of a civil engineer, Czesław Miłosz completed his university studies in Wilno (now Vilnius, Lithuania), which belonged to Poland between the two world wars. His first book of verse, Poemat o czasie zastygłym (1933; “Poem of Frozen Time”), expressed catastrophic fears of impending war and worldwide disaster. During the Nazi occupation, he moved to Warsaw, where he was active in the resistance and edited Pieśń niepodległa (1942; “Independent Song: Polish Wartime Poetry”), a clandestine anthology of well-known contemporary poems.

After receiving his law degree in 1934, he spent a year in Paris on a fellowship. Upon returning, he worked as a commentator at Radio Wilno but was dismissed. This action has been described as stemming from either his leftist views or for views overly sympathetic to Lithuania. Miłosz wrote all his poetry, fiction and essays in Polish and translated the Old Testament Psalms into Polish. He published his second poetry collection ‘Trzy zimy’ (Three Winters), which was well-received by literary critics.

He went to Vilnius by then under Soviet occupation and eventually returned to German-controlled Warsaw after a perilous trip. There, he worked with the anti-German resistance movement and served as a poetry editor for an underground publisher. Some of his most moving poems, such as “A Poor Christian Looks at the Ghetto,” chronicle the tragedies of this period, including the walling off of Warsaw’s Jews into a ghetto, where countless died.

Miłosz spent World War II in Warsaw, under Nazi Germany’s “General Government”. Here he attended underground lectures by Władysław Tatarkiewicz, the Polish philosopher and historian of philosophy and aesthetics. He did not join the Polish Home Army’s resistance or participate in the Warsaw Uprising, partly from an instinct for self-preservation and partly because he saw its leadership as right-wing and dictatorial.

After World War II, Milosz worked for the Polish embassy in New York City and was later posted to Paris. He still wrote but was wary of the new cultural dictates from Poland’s Communist regime. Artistic output, according to the party line, should conform to certain political ideals, and this included new literary works. When he learned in 1951 that he was about to be detained, he sought political asylum in France. His landmark 1953 work, The Captive Mind, argued that doctrinaire authoritarian regimes stifle intellectual output. In it, he provided thinly disguised case histories that recounted the brainwashing tactics used on some leading Polish cultural icons in recent years. Milosz was not hesitant about criticizing the left in the West, either: in other writings and interviews, he mocked the French left’s flirtation with communism and its adoration of Soviet tyrant Josef Stalin. Some of this was retributive: he had arrived in France as a political exile, and was virtually destitute; prominent figures of the left-leaning literary world treated him coolly, and he had a difficult time finding a publisher during these years.

He released ‘Ocalenie’ (Rescue) in 1945 as a collection of pre-war and wartime poems, which went on to become one of the most notable works of 20th-century Polish poetry.

In his 1953 book The Captive Mind, however, Miłosz would later sharply criticize the Soviet military for remaining in their positions and making no effort to assist the Home Army’s fighters. He accused them of watching through binoculars as the Polish Resistance was slaughtered and as the city was razed by Hitler’s orders. Only then did the Soviets enter the city.

Nine years later he immigrated to the United States, where he joined the faculty of the University of California at Berkeley and taught Slavic languages and literature until his retirement in 1980. Miłosz became a naturalized citizen of the United States in 1970.

During his defection in Paris, he worked as a freelance writer, authoring novels ‘The Captive Mind’ (1953), ‘The Seizure of Power’ (1955), ‘The Issa Valley’ (1955), and autobiography ‘Native Realm: A Search for Self Definition’ (1959). He completed two volumes of poetry, namely, ‘The Light of Day’ (1954) and ‘A Poetical Treatise’ (1957), which were banned in Poland and later published by the Instytut Literacki in Paris.

Milosz left France when the University of California offered him a professorship. After 1961, he taught Slavic languages and literature at the university’s vibrant Berkeley campus, where his classes were popular with several generations of students. He became an American citizen but still wrote his poems in Polish. The epic “Gdzie slonce wschodzi I kedy zapada” (From the Rising of the Sun), from 1974, is considered one of his best works and was part of an impressive body of work that brought him the 1980 Nobel Prize in literature.

In 1978 he received the Neustadt International Prize for Literature. He retired the same year but continued teaching at Berkeley. His attitude about living in Berkeley is sensitively portrayed in his poem, “A Magic Mountain,” contained in a collection of translated poems, Bells in Winter (Ecco Press, 1985).

In 1977, Miłosz had been given an honorary doctorate by the University of Michigan; two weeks after he received the 1980 Nobel Prize in Literature, he returned to Michigan to lecture, and in 1983 he became the Visiting Walgreen Professor of Human Understanding.

For years, his works were banned in Poland and were circulated only through underground sources, but after he received the Nobel Prize in 1980, the communist government relented and his works started getting issued legally. His popular prose works include ‘The History of Polish Literature’ (1969), ‘Visions from San Francisco Bay’ (1969), ‘Private Obligations’ (1974), ‘The Land of Ulro’ (1977), ‘The Witness of Poetry’ (1983), and ‘Starting from My Streets’ (1985).

Among his renowned poetry collections are ‘Unattainable Earth’ (1984), ‘Chronicles’ (1989), ‘Facing the River’ (1994), ‘Orpheus and Eurydice’ (2003), and ‘Last Poems’ (2006).

There are several volumes of English translations of Miłosz’s poetry, including The Collected Poems 1931–1987 (1988) and Provinces (1991). His prose works include his autobiography, Rodzinna Europa (1959; Native Realm), Prywatne obowiązki (1972; “Private Obligations”), the novel Dolina Issy (1955; The Issa Valley), and The History of Polish Literature (1969).

Apart from authoring a diverse range of prose and poetry works, he also translated works of other Polish writers into English and released a Polish version of the Old Testament ‘Psalms’. His translations into Polish included works of other distinguished writers, such as William Shakespeare, Charles Baudelaire, Walt Whitman, John Milton, T.S. Eliot, and Simone Weil.

Awards and Honor

Miłosz received the Prix Litteraire Europeen (European Literary Prize) for his novel ‘The Seizure of Power’ from the Swiss Book Guild, in 1953.

In 1971, Miłosz won an award from the Polish P.E.N. Club, Warsaw, for his poetry translations. He won a Guggenheim Fellowship for poetry and received an honorary Doctor of Letters degree from the University of Michigan, in 1977.

In 1978 he received the Neustadt International Prize for Literature.

Miłosz was honored with the prestigious Nobel Prize for Literature in 1980.

In 1989 he received the U.S. National Medal of Arts and an honorary doctorate from Harvard University.

In 1989, he won a ‘Righteous among the Nations’ medal in Yad Vashem, Israel, towards his active participation in the “The ‘Freedom’ Socialist Pro-Independence Organization” during the Holocaust. He was granted honorary citizenship of Lithuania in 1992 and of Krakow city in 1993.

The Czeslaw Milosz Award was established by the Lithuania National Artists Association, Journalists’ Union in Lithuania and Polish Institute in Vilnius to award unique and finest literary works in Poland and Lithuania.

Death and Legacy

By the end of that decade, Communism in Poland had retreated, and Milosz was able to return. He was hailed as a national literary icon, a voice of Poland’s conscience, and spent the remainder of his years in Krakow.

Czesław Miłosz died on 14 August 2004 at his Kraków home, aged 93. He was buried in Kraków’s Skałka Roman Catholic Church, becoming one of the last to be commemorated there.

Though Miłosz was primarily a poet, his best-known work became his collection of essays Zniewolony umysł (1953; The Captive Mind), which condemned the accommodation of many Polish intellectuals to communism. This theme is also present in his novel Zdobycie władzy (1955; The Seizure of Power). His poetic works are noted for their classical style and their preoccupation with philosophical and political issues. An important example is Traktat poetycki (1957; Treatise on Poetry), which combines a defense of poetry with a history of Poland from 1918 to the 1950s. The critic Helen Vendler wrote that this long poem seemed to her “the most comprehensive and moving poem” of the latter half of the 20th century.

The year 2011 was declared as ‘The Milosz Year’, which saw a conference on his relations with America at the Yale University, an exhibition of his works by the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, and a large conference in Krakow.

Information Source: