The amygdala is a deep brain region that is roughly the size and shape of an almond, thus its name. It is usually referred to as a center for sensing hazards in the environment as well as processing fear and other emotions. Researchers that study the region contend that its function is broader — and that it is important in autism.

A long-term study including hundreds of brain scans shows that abnormalities in the amygdala are associated with the development of anxiety in autistic children. The UC Davis MIND Institute study also found evidence of multiple types of anxiety associated with autism. The study was published in the journal Biological Psychiatry.

“I believe this is the first study to find any kind of biological relationship with these autism-specific fears,” said Derek Sayre Andrews, a postdoctoral scholar in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences and co-first author on the publication. “Anxiety is really prevalent right now because to the pandemic, and it can be debilitating for autistic people, so it’s critical to understand what’s going on in the brain.”

The importance of the amygdala in autism and anxiety

The amygdala is a small, almond-shaped structure in the brain. It plays a key role in processing emotion, particularly fear, and have linked it to both autism and anxiety.

“We’ve known for a long time that amygdala dysregulation is involved in anxiety,” said David G. Amaral, UC Davis distinguished professor, Beneto Foundation Endowed Chair, and co-senior author on the study. “We’ve also previously demonstrated that the amygdala’s maturation trajectory is disrupted in many autistic individuals.”

Anxiety is a typical symptom of autism. Previous research conducted by Amaral and other MIND Institute experts discovered that the rate of anxiety is. But, until today, no one had looked at the growth of the amygdala in autistic people over time in relation to different types of anxiety.

Previous research did not distinguish amygdala size in relation to these two types of anxiety. If we had combined traditional and distinct concerns, the amygdala modifications would have cancelled each other out, and we would not have found these diverse patterns of amygdala growth.

Christine Wu Nordahl

Hundreds of brain scans

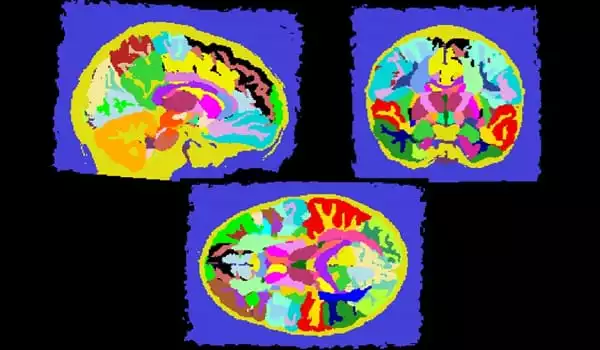

The researchers employed magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to scan the brains of 71 autistic and 55 non-autistic youngsters aged 2 to 12. Children were scanned as many as four times. All were participants in the Autism Phenome Project, a long-term study that began at the MIND Institute in 2006.

Autism-specialist clinical psychologists interviewed the parents about their children. The interviews were conducted with youngsters aged 9 to 12. They asked about typical anxiety as described by the DSM-5, a guideline used to diagnose mental health problems. The psychologists employed the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule (ADIS) as well as the Autism Spectrum Addendum (ASA), which was created to elicit autism-specific fears.

The results showed that nearly half of the autistic children had traditional anxiety or autism-distinct anxiety, or both. Autistic children with traditional anxiety had significantly larger amygdala volumes compared to non-autistic children. The opposite was true for autistic children with autism-distinct anxieties: They had significantly smaller amygdala volumes.

“Previous research did not distinguish amygdala size in relation to these two types of anxiety,” said Christine Wu Nordahl, a professor in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences and co-senior author of the paper. “It was brought to our attention that distinct autistic subgroups may have different underlying brain abnormalities. If we had combined traditional and distinct concerns, the amygdala modifications would have canceled each other out, and we would not have found these diverse patterns of amygdala growth.”

Nordahl and Amaral have been tracking autistic subgroups in the Autism Phenome Project for 15 years and have published various research that have advanced the field of knowledge in this area.

“The real power of this particular study is that it tracks the trajectory of amygdala development from age 2 to age 12 to see if there are early predictors of these different types of anxiety — whether there are different patterns.” Nordahl said.

Autism-specific anxiety versus traditional anxiety

Previous study has revealed that anxiety in autistic people is complicated. In circumstances familiar to non-autistic persons, some people experience classic anxiety, which might involve scared avoidance. Others, on the other hand, may experience anxiety in autism-specific circumstances.

“It’s comparable,” Andrews observed, “but the situation in which the fear originates is different.” “It could be unusual phobias like facial hair or toilet seats, or it could be social anxiety or extreme worry about losing access to materials about something they’re truly interested in. It’s anxiety manifested in an autistic situation.”

The study into autism-specific anxiety is new, and the authors warn that the findings need to be confirmed, but the study makes a compelling argument for it. “Given that evident brain abnormalities are connected with autism-distinct anxiety,” Amaral said, “it tends to confirm the hypothesis of the existence of this sort of anxiety in autism.” In fact, 15% of the participants in the study solely experienced autism-specific anxiety.

“You can see why it’s crucial to recognize this, since these youngsters would be missed through standard screening,” Andrews noted. He went on to say that this form of worry may necessitate specific treatment. “That’s why it’s critical to understand the underlying biology of anxiety and autism, and to assist these children in any way we can.”

The researchers intend to investigate how the amygdala interacts with other brain regions in the future. “We don’t believe the tale finishes with the amygdala,” Nordahl explained. “We realize that it does not behave in isolation, and it is vital to investigate who the amygdala is communicating with and what it is doing via its network of connections with other brain regions.”