A star can consume a planet in its orbit, which astronomers can detect through various methods such as changes in the star’s brightness or the chemical composition of its atmosphere. However, because such events are rare and difficult to observe, astronomers would make a significant discovery if they were to spot a star swallowing a planet.

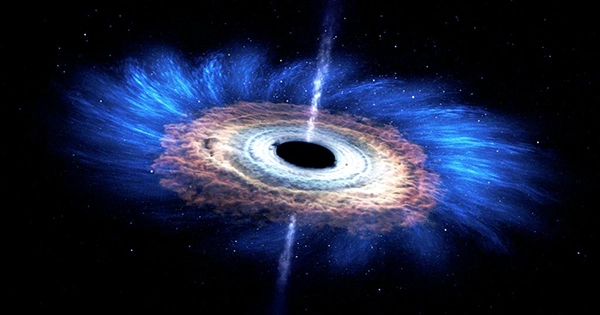

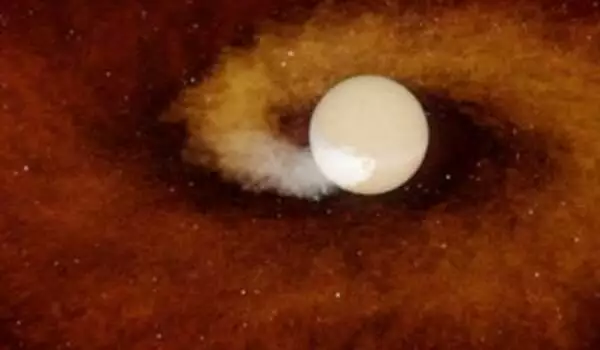

For the first time, scientists have observed a star devouring a planet. In 5 billion years, Earth will face a similar fate. When a star runs out of fuel, it expands to a million times its original size, engulfing all matter – and planets – in its path. Scientists have seen hints of stars just before and after they consume entire planets, but they have never seen one in action until now.

For the first time, scientists from MIT, Harvard University, Caltech, and other institutions report in Nature that they have observed a star swallowing a planet.

The planetary extinction appears to have occurred in our own galaxy, approximately 12,000 light-years away, near the eagle-like constellation Aquila. Astronomers discovered an outburst from a star that grew more than 100 times brighter in just 10 days before rapidly fading away. This white-hot flash was strangely followed by a colder, longer-lasting signal. The scientists deduced that this combination could only have resulted from one event: a star engulfing a nearby planet.

We are seeing the future of the Earth. If another civilization were observing us from 10,000 light-years away while the sun was engulfing the Earth, they would see the sun suddenly brighten as it ejects some material, then form dust around it, before settling back to what it was.

Deepto Chakrabarty

“We were seeing the end-stage of swallowing,” says lead author Kishalay De, a postdoctoral researcher at MIT’s Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research.

What happened to the planet? The scientists believe it was a hot, Jupiter-sized world that spiraled close to the dying star, then was drawn into its atmosphere, and finally into its core. A similar fate awaits the Earth, though not for another 5 billion years, when the sun will burn out and destroy the solar system’s inner planets.

“We are seeing the future of the Earth,” De says. “If another civilization were observing us from 10,000 light-years away while the sun was engulfing the Earth, they would see the sun suddenly brighten as it ejects some material, then form dust around it, before settling back to what it was.”

The study’s MIT co-authors include Deepto Chakrabarty, Anna-Christina Eilers, Erin Kara, Robert Simcoe, Richard Teague, and Andrew Vanderburg, along with colleagues from Caltech, the Harvard and Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, and multiple other institutions.

Hot and cold

In May 2020, the team discovered the outburst. However, it took another year for the astronomers to piece together an explanation for the outburst. The initial signal was discovered during a data search conducted by the Zwicky Transient Facility (ZTF) at Caltech’s Palomar Observatory in California. The ZTF is a survey that scans the sky for stars that change brightness rapidly, the pattern of which could be evidence of supernovae, gamma-ray bursts, and other stellar phenomena.

De was searching through ZTF data for signs of stellar binary eruptions, which occur when two stars orbit each other, with one pulling mass from the other and brightening briefly as a result.

“One night, I noticed a star that brightened by a factor of 100 over the course of a week, out of nowhere,” De recalls. “It was unlike any stellar outburst I had seen in my life.”

De looked to observations of the same star taken by the Keck Observatory in Hawaii in the hopes of narrowing down the source with more data. The Keck telescopes collect spectroscopic measurements of starlight that scientists can use to determine the chemical composition of stars. But what De discovered perplexed him even more. While most binaries emit stellar material like hydrogen and helium as one star erodes the other, the new source did not. Instead, De saw evidence of “unusual molecules” that can only exist at extremely low temperatures.

“These molecules are only seen in very cold stars,” De says. “And when a star shines brighter, it usually gets hotter.” Low temperatures and brightening stars do not mix.”

“A happy coincidence”

It was then clear that the signal was not of a stellar binary. De decided to wait for more answers to emerge. About a year after his initial discovery, he and his colleagues analyzed observations of the same star, this time taken with an infrared camera at the Palomar Observatory. Within the infrared band, astronomers can see signals of colder material, in contrast to the white-hot, optical emissions that arise from binaries and other extreme stellar events.

“That infrared data made me fall off my chair,” De says. “The source was insanely bright in the near-infrared.”

After its initial hot flash, it appeared that the star continued to emit colder energy over the next year. That icy substance was most likely gas from the star that exploded into space and condensed into dust, which was cold enough to be detected at infrared wavelengths. This data suggested that the star was merging with another star rather than brightening due to a supernova explosion.

When the team analyzed the data further and compared it to measurements taken by NASA’s infrared space telescope, NEOWISE, they came to a much more exciting conclusion. From the compiled data, they estimated the total amount of energy released by the star since its initial outburst, and found it to be surprisingly small – about 1/1,000 the magnitude of any stellar merger observed in the past.

“That means that whatever merged with the star has to be 1,000 times smaller than any other star we’ve seen,” De says. “And it’s a happy coincidence that the mass of Jupiter is about 1/1,000 the mass of the sun. That’s when we realized: This was a planet, crashing into its star.”

The scientists were finally able to explain the initial outburst with all of the pieces in place. The bright, hot flash was most likely the final moments of a Jupiter-sized planet being drawn into the ballooning atmosphere of a dying star. The outer layers of the star blasted away as the planet fell into the star’s core, settling out as cold dust over the next year.

“For decades, we’ve been able to see the before and after,” says De. “Before, when the planets are still very close to their star, and after, when a planet has already been engulfed and the star is massive.” What we were missing was catching the star in the act, with a planet going through this fate in real time. That’s what makes this discovery really exciting.”