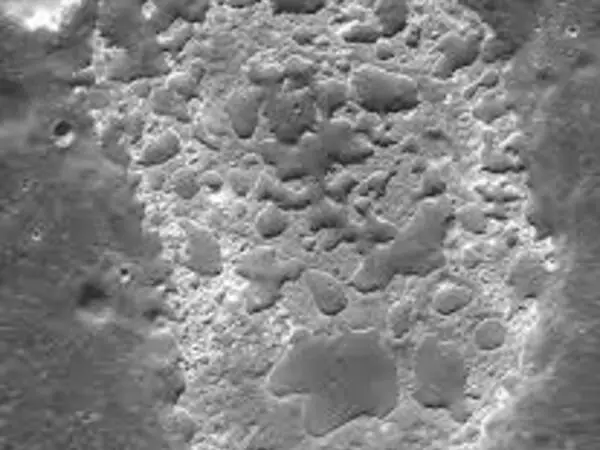

If humans were alive 2 to 4 billion years ago, they might have noticed a sliver of frost on the moon’s surface. Some of that ice may still be present in lunar craters today. A series of volcanic eruptions erupted on the moon billions of years ago, covering hundreds of thousands of square miles of the orb’s surface in hot lava. That lava formed the dark blotches, or maria, that give the moon’s face its familiar appearance today over eons.

New research from CU Boulder suggests that volcanoes may have left another lasting impact on the lunar surface: sheets of ice that dot the moon’s poles and, in some places, could be dozens or even hundreds of feet thick.

“We imagine it as a frost on the moon that accumulated over time,” said Andrew Wilcoski, lead author of the new study and a graduate student in the Department of Astrophysical and Planetary Sciences (APS) and the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics (LASP) at CU Boulder.

He and his colleagues published their findings this month in The Planetary Science Journal.

The scientists used computer simulations, or models, to try to recreate conditions on the moon long before complex life appeared on Earth. They discovered that ancient moon volcanoes emitted massive amounts of water vapor, which settled onto the surface, forming ice stores that may still exist in lunar craters. If any humans had been alive at the time, they might have seen a sliver of that frost on the moon’s surface near the border between day and night.

We imagine it as a frost on the moon that accumulated over time. Volcanoes could be a big one. The planetary scientist explained that from 2 to 4 billion years ago, the moon was a chaotic place.

Andrew Wilcoski

According to study co-author Paul Hayne, it could be a boon for future moon explorers who will need water to drink and process into rocket fuel. “It’s possible that 5 or 10 meters below the surface, you have big sheets of ice,” said Hayne, assistant professor in APS and LASP.

Temporary atmospheres

The new study adds to a growing body of evidence suggesting that the moon may contain far more water than scientists previously thought. Hayne and his colleagues estimated in a 2020 study that nearly 6,000 square miles of the lunar surface could be capable of trapping and clinging to ice, mostly near the moon’s north and south poles. It’s unclear where all that water came from in the first place.

“At the moment, there are a lot of potential sources,” Hayne said.

Volcanoes could be a big one. The planetary scientist explained that from 2 to 4 billion years ago, the moon was a chaotic place. Tens of thousands of volcanoes erupted across its surface during this period, generating huge rivers and lakes of lava, not unlike the features you might see in Hawaii today — only much more immense.

“They dwarf almost all of the eruptions on Earth,” Hayne said.

According to recent research from the Lunar and Planetary Institute in Houston, these volcanoes ejected towering clouds primarily composed of carbon monoxide and water vapor. These clouds then swirled around the moon, possibly creating thin and fleeting atmospheres. That made Hayne and Wilcoski wonder if the same atmosphere could have left ice on the lunar surface, similar to frost forming on the ground after a cold fall night.

Forever ice

To find out, the duo, along with Margaret Landis, a research associate at LASP, set out billions of years ago to try to land on the moon’s surface. The team used estimates that, at its peak, the moon erupted once every 22,000 years on average. The researchers then studied how volcanic gases might have swirled around the moon, eventually escaping into space. They also discovered that the conditions had possibly become icy. According to the group’s estimates, approximately 41 percent of the water from volcanoes may have condensed as ice on the moon.

“The atmospheres escaped over about 1,000 years, so there was plenty of time for ice to form,” Wilcoski explained.

There could have been so much ice on the moon that you could have seen the sheen of frost and thick polar ice caps from Earth. During that time, the group calculated that approximately 18 quadrillion pounds of volcanic water could have condensed as ice. That is more water than Lake Michigan currently has. And the research suggests that some of that lunar water may still exist today.

Those space ice cubes, on the other hand, will not be easy to come by. The majority of that ice has most likely accumulated near the moon’s poles and may be buried beneath several feet of regolith, or lunar dust. Another reason, according to Hayne, for people or robots to return and begin digging.