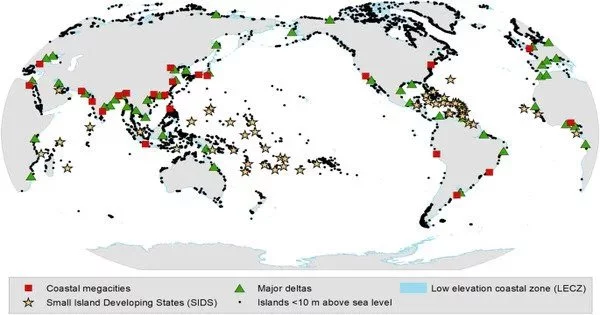

Asian megacities are particularly vulnerable to sea level rise due to a combination of factors such as their geographical location, dense population, and high levels of economic development. According to new research that examines the effects of natural sea-level fluctuations on the projected rise due to climate change, sea level rise this century may disproportionately affect certain Asian megacities, as well as western tropical Pacific islands and the western Indian Ocean.

The study, led by scientists from the French National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS) and the University of La Rochelle in France, was co-authored by a scientist from the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR). The study’s findings suggest that several Asian megacities, including Chennai, Kolkata, Yangon, Bangkok, Ho Chi Minh City, and Manila, may face especially serious risks by 2100 if society continues to emit high levels of greenhouse gases.

Scientists have long known that rising sea levels are caused by rising ocean temperatures, owing to the fact that water expands when it warms and melting ice sheets release more water into the oceans. According to studies, sea level rise will vary regionally due to changes in ocean currents, which will likely direct more water to certain coastlines, including the northeastern United States.

Internal climate variability can greatly reinforce or suppress the sea level rise caused by climate change. In the worst-case scenario, the combined effect of climate change and internal climate variability could result in local sea levels rising by more than 50% of what climate change alone would cause, posing significant risks of more severe flooding to coastal megacities and threatening millions of people.

Aixue Hu

The new study is notable for how it incorporates naturally occurring sea level fluctuations caused by events such as El Nio or changes in the water cycle (a process known as internal climate variability). The scientists could determine the extent to which natural fluctuations can amplify or reduce the impact of climate change on sea level rise along specific coastlines by using both a computer model of global climate and a specialized statistical model.

Internal climate variability, according to the study, could increase sea level rise in some locations by 20-30% more than climate change alone, exponentially increasing extreme flooding events.

In Manila, for example, coastal flooding events are predicted to occur 18 times more often by 2100 than in 2006, based solely on climate change. But, in a worst-case scenario, they could occur 96 times more often based on a combination of climate change and internal climate variability.

Sea level rise along the west coasts of the United States and Australia will be exacerbated by internal climate variabilit. The study relied on a series of simulations run with the NCAR-based Community Earth System Model, which assumes society will emit a large amount of greenhouse gases this century. The NCAR-Wyoming Supercomputing Center was used to run the simulations.

The paper emphasized that estimates of sea level rise are subject to significant uncertainty due to the complex and unpredictable interactions in the Earth’s climate system. However, the authors argue that society must be aware of the potential for extreme sea level rise in order to develop effective adaptation strategies.

“Internal climate variability can greatly reinforce or suppress the sea level rise caused by climate change,” said NCAR co-author Aixue Hu. “In the worst-case scenario, the combined effect of climate change and internal climate variability could result in local sea levels rising by more than 50% of what climate change alone would cause, posing significant risks of more severe flooding to coastal megacities and threatening millions of people.”

The findings were published in the journal Nature Climate Change. It was funded by the French Research Agency, the United States Department of Energy, and the National Science Foundation, which also serves as NCAR’s sponsor.