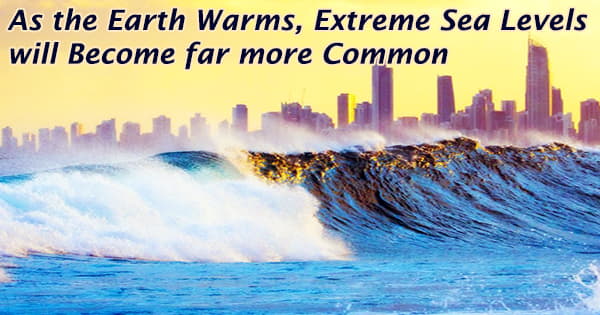

Severe climate and weather events have dominated the news in recent months, including record-breaking temperatures from the Pacific Northwest to Sicily, flooding in Germany and the eastern United States, and wildfires raging from Sacramento to Siberia to Greece. Events that were once considered unusual are now routine.

New research published on August 30 (2021) in the journal Nature Climate Change examines extreme sea levels, or the occurrence of unusually high seas caused by a mix of the tide, waves, and storm surge. According to the study, high sea levels along coasts across the world would become 100 times more common by the end of the century in roughly half of the 7,283 sites analyzed as a result of rising temperatures.

That implies that, as a result of rising temperatures, a severe sea-level event that would have occurred once every 100 years is now anticipated to occur every year by the end of the century. While the researchers acknowledge that future climate is unknown, the most likely route is for these increased occurrences of sea-level rise to occur even if global temperatures climb 1.5 or 2 degrees Celsius over preindustrial levels.

These temperatures are thought to be on the lower end of the range of probable global warming, according to scientists. By 2070, several areas will have seen a 100-fold increase in severe sea level occurrences, indicating that the changes will occur sooner than the end of the century.

Mapping effects, location by location –

A multinational team of researchers was directed by Claudia Tebaldi, a climate scientist at the Department of Energy’s Pacific Northwest National Laboratory. She gathered experts who had previously undertaken extensive research on extreme sea levels and the implications of climate change on sea-level rise.

To map out anticipated impacts of temperature rises ranging from 1.5 C to 5 C relative to preindustrial periods, the researchers pooled their data and used a unique synthesis approach, considering different estimates as expert votes. The research discovered that the impacts of increasing oceans on severe sea level frequency will be felt most strongly in the tropics and at lower latitudes than in northern regions, which is not surprising.

The Southern Hemisphere, regions along the Mediterranean Sea and the Arabian Peninsula, the southern half of North America’s Pacific coast, and areas such as Hawaii, the Caribbean, the Philippines, and Indonesia are all expected to be affected the most. Sea level is predicted to rise quicker in several of these areas than in higher latitudes.

The higher latitudes, as well as the northern Pacific coast of North America and the Pacific coast of Asia, will be less affected.

“One of our central questions driving this study was this: How much warming will it take to make what has been known as a 100-year event an annual event? Our answer is, not much more than what has already been documented,” said Tebaldi, who notes that the globe has already warmed about 1 C compared to preindustrial times.

The new analysis backs up the findings of the 2019 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report, which predicted that owing to global warming, severe sea level occurrences will become considerably more likely by the end of the century.

“It’s not huge news that sea-level rise will be dramatic even at 1.5 degrees and will have substantial effects on extreme sea level frequencies and magnitude,” said Tebaldi. “This research provides a more comprehensive view of the situation throughout the world. We were able to investigate a broader variety of warming levels in great detail.”

The research’s best and worst-case scenarios differ due to uncertainties that the authors of the study described in great detail. At 1.5 degrees Celsius of warming, 99 percent of places analyzed will suffer a 100-fold increase in severe occurrences by 2100, according to one gloomy scenario. On the other hand, even if the temperature rises by 5 degrees Celsius, roughly 70% of areas will experience no change.

More research is needed, according to the authors, to fully comprehend how the changes would effect specific groups. They note out that the physical changes described in their study will have varied consequences at local scales, depending on a variety of factors such as the site’s vulnerability to rising seas and the community’s readiness for change.

Authors of the paper include Roshanka Ranasinghe of the IHE Delft Institute for Water Education in the Netherlands; Michalis Vousdoukas of the European Joint Research Centre in Italy; D.J. Rasmussen of Princeton University; Ben Vega-Westhoff and Ryan Sriver of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign; Ebru Kirezci of the University of Melbourne in Australia; Robert E. Kopp of Rutgers University; and Lorenzo Mentaschi of the University of Bologna in Italy.

The corresponding author, Tebaldi, is a scientist at the Joint Global Change Research Institute, a collaboration between PNNL and the University of Maryland that studies the connections between humans, energy, and the environment. The US Environmental Protection Agency and the Office of Science of the Department of Energy supported the research.