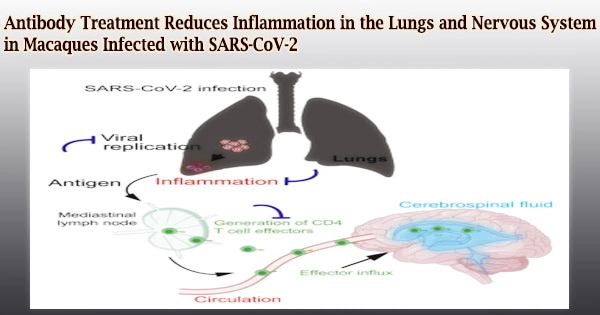

According to a new study from researchers at the University of California, Davis, monoclonal antibodies protected elderly diabetic rhesus macaque monkeys from SARS-CoV-2 sickness and reduced symptoms of inflammation, including in the cerebrospinal fluid. It published the findings in the journal Cell Reports on October 18th.

The findings demonstrate that neutralizing antibodies protect against the inflammatory effects of SARS-CoV-2 infection, according to scientists. The findings shed light on how antibodies, whether produced by vaccines, acquired after infection, or administered as a treatment, can influence disease progression.

Antibodies could potentially be administered as a preventative treatment to patients who are at high risk, such as elderly residents in nursing homes during an outbreak.

“COVID-19 is more severe in elderly people and those with pre-existing conditions,” said Smita Iyer, associate professor of pathology, microbiology, and immunology at the UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine and Center for Immunology and Infectious Disease, and a core investigator at the California National Primate Research Center.

“The elderly and diabetics tend to be immunosuppressed, but if you can get antibody levels high enough, you can prevent severe infection,” she said.

Vaccine-induced immune responses are extremely successful at preventing serious disease and death. However, an overactive inflammatory immune response could be to blame for much of the harm caused by severe infections.

COVID-19 is more severe in elderly people and those with pre-existing conditions. The elderly and diabetics tend to be immunosuppressed, but if you can get antibody levels high enough, you can prevent severe infection.

Smita Iyer

Vaccine-induced immune responses are extremely successful at preventing serious disease and death. However, an overactive inflammatory immune response could be to blame for much of the harm caused by severe infections.

“We want to know, what are the immune determinants of disease,” Iyer said.

In elderly, diabetic rhesus macaques, Iyer, graduate student Jamin (J.W.) Roh, postdoctoral fellow Anil Verma, and colleagues tested two human monoclonal antibodies that target the spike protein of the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

The macaques were around the same age as humans in their mid-60s when they were 21 to 22 years old. They had developed hypertension and diabetes, like many other elderly humans, but were otherwise healthy. Antibodies were given to the animals three days before they were infected with SARS-CoV-2.

Preventing inflammation in the central nervous system

Infections with COVID in rhesus macaques were often minor, especially in animals that had been given monoclonal antibodies. The lungs of control animals showed increased symptoms of inflammation.

A week after infection, the researchers discovered infiltration of activated immune cells, or T cells, into the cerebral fluid of control mice. In the cerebrospinal fluid, no viral RNA was found. Antibodies did not cause inflammation in the cerebrospinal fluid in macaques.

These signals of inflammation in the central nervous system could be linked to the neurological symptoms of COVID-19 disease in humans, as well as “long COVID,” in which patients suffer from a variety of symptoms for months following infection.

Additional authors on the paper are: at UC Davis, Chase Hawes, Yashavanth Shaan Lakshmanappa, Brian Schmidt, Joseph Dutra, William Louie, Hongwei Liu, Zhong-Min Ma, Jennifer Watanabe, Jodie Usachenko, Ramya Immareddy, Rebecca Samak, Rachel Pollard, J. Rachel Reader, Katherine Olstad, Lark Coffey, Dennis Hartigan-O’Connor, Koen Van Rompay and John Morrison; Pamela Kozlowski, Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center, New Orleans; and Michael Nussenzweig, The Rockefeller University, New York. The work was supported by grants from the NIH.