For the first time in mice, a research team from the Pompeu Fabra University (UPF) Department of Medicine and Life Sciences (MELIS) and the Hospital del Mar Research Institute has identified and validated the neurobiological mechanism and therapy to correct memory deficit in people with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD).

These findings pave the door for further research into whether the system operates similarly in humans, which will help to better diagnose and treat those who are afflicted.

Infants who have been exposed to alcohol during pregnancy may experience a number of problems collectively known as fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD). The symptoms of FASD range from hyperactivity, emotional and motivational challenges, or deficiencies in learning and memory in the mildest cases, to craniofacial morphological deformities or growth issues in the most severe cases.

“In children of normal appearance, FASD is underdiagnosed and is often mistaken for hyperactivity or ADD,” explains Rafael de la Torre, coordinator of the Integrated Pharmacology and Systems Neuroscience Research Group at the Hospital del Mar Research Institute. “Since there is no diagnosis, there is no treatment, and symptomatic therapy is given to alleviate hyperactivity or other disorders such as anxiety.”

The results of the study published in the journal Molecular Psychiatry, have allowed the researchers to observe that “exposure to alcohol need not be chronic for FASD to occur. Sporadic consumption ending in intoxication getting drunk is enough to observe alterations in memory, in mice,” explains Olga Valverde, study coordinator and director of the Research Group in Behavioral Neurobiology at the MELIS-UPF.

In this work we have only studied alterations in memory, but there may be emotional, motivational or behavioral alterations related to fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD).

Olga Valverde

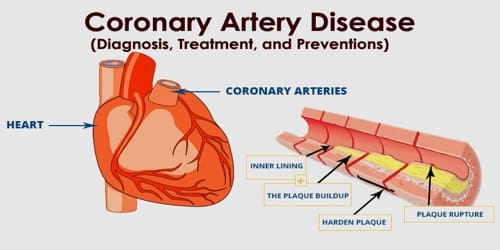

According to the study, mice born to moms who drank alcohol seldom while pregnant and nursing have memory deficits that last into adulthood. One of the reasons for this deficit is that alcohol affects the function of the endocannabinoid system, reducing the expression of the PPAR-? receptor.

“The endocannabinoid system is greatly involved in learning and memory processes,” de la Torre explains. “That is why it is especially relevant that this decrease occurs during infancy, when the mice, male and female, are of learning age.”

However, the reduction in PPAR-? does not occur throughout the brain. It only affects the hippocampal astrocyte cells, which provide support for the neurons in the hippocampus and regulate processes like their metabolism or the inflammation to which they are exposed.

The study also suggests a successful treatment using the medication pioglitazone, which is frequently used to regulate sugar and which stimulates PPAR receptors, after establishing the neurobiological mechanism by three separate means.

According to the first author of the study, Alba Garcia-Baos, “manages to alleviate the cognitive memory deficits of individuals with FASD in infancy.”

Optimism regarding studies in humans

The findings of this investigation open the door to research into other cognitive deficits brought on by alcohol consumption during pregnancy.

“In this work we have only studied alterations in memory, but there may be emotional, motivational or behavioral alterations related to FASD,” points out Valverde, who is also a full professor of Psychobiology at UPF.

Although this study has been conducted in mice, the researcher is optimistic about confirming that this mechanism is replicated in humans “because we are two species of mammals that share many similarities.”

In addition, if confirmed, “it would be relatively simple to carry out a study to validate whether the therapy we propose works in humans, since there are drugs that have similar effects to the ones we have used that are approved for use in children.”