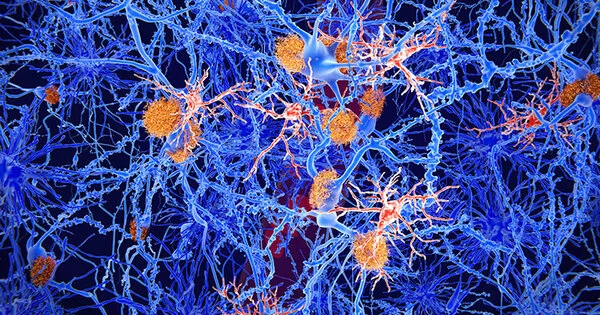

The innate immune system is heavily involved in Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis (AD). In contrast, the role of adaptive immunity in Alzheimer’s disease is still largely unknown. Several clinical trials are currently testing vaccination strategies for Alzheimer’s disease, indicating that T and B cells play an important role in this disease.

A new study discovered that cerebrospinal fluid, the brain’s immune system, becomes dysregulated as we age and plays a newly discovered role in cognitive impairment in diseases like Alzheimer’s. Because your three-pound brain floats in a reservoir of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), which flows in and around your brain and spinal cord, it does not feel heavy. This liquid barrier between your brain and your skull protects it from a blow to the head and nourishes it. However, the CSF serves another important, albeit less well-known, function: it protects the brain from infection. Nonetheless, this function has received little attention.

A Northwestern Medicine study of CSF has discovered its role in cognitive impairment, such as Alzheimer’s disease. This discovery provides a new clue to the process of neurodegeneration, said study lead author David Gate, assistant professor of neurology at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine.

The study will be published in Cell.

We now have a glimpse into the brain’s immune system with healthy aging and neurodegeneration. This immune reservoir could potentially be used to treat inflammation of the brain or be used as a diagnostic to determine the level of brain inflammation in individuals with dementia.

David Gate

The study found that, as people age, their CSF immune system becomes dysregulated. In people with cognitive impairment, such as those with Alzheimer’s disease, the CSF immune system is drastically different from healthy individuals, the study also discovered.

“We now have a glimpse into the brain’s immune system with healthy aging and neurodegeneration,” Gate said. “This immune reservoir could potentially be used to treat inflammation of the brain or be used as a diagnostic to determine the level of brain inflammation in individuals with dementia.”

“We provide a thorough analysis of this important immunologic reservoir of the healthy and diseased brain,” Gate said. His team is sharing the data publicly, and its results can be searched online.

To analyze the CSF, Gate’s team at Northwestern used a sophisticated technique called single-cell RNA sequencing. They profiled 59 CSF immune systems from a spectrum of ages by taking CSF from participants’ spines and isolating their immune cells.

The first part of the study looked at CSF in 45 healthy individuals aged 54 to 83 years. The second part of the study compared those findings in the healthy group to CSF in 14 adults with cognitive impairment, as determined by their poor scores on memory tests.

Gate’s team of scientists observed genetic changes in the CSF immune cells in older healthy individuals that made the cells appear more activated and inflamed with advanced age.

“The immune cells appear to be a little angry in older individuals,” Gate said. “We think this anger might make these cells less functional, resulting in dysregulation of the brain’s immune system.”

In the cognitively impaired group, inflamed T-cells cloned themselves and flowed into the CSF and brain as if they were following a radio signal, Gate said. Scientists found the cells had an overabundance of a cell receptor – CXCR6 – that acts as an antenna. This receptor receives a signal – CXCL16 – from the degenerating brain’s microglia cells to enter the brain.

“It could be the degenerating brain activates these cells and causes them to clone themselves and flow to the brain,” Gate said. “They do not belong there, and we are trying to understand whether they contribute to damage in the brain.”

Gate said his “future goal is to block that radio signal or to inhibit the antenna from receiving that signal from the brain. We want to know what happens when these immune cells are blocked from entering brains with neurodegeneration.”

Gate’s laboratory will continue to explore the role of these immune cells in brain diseases like Alzheimer’s. They also plan to expand to other diseases, such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS).

This work was in part supported by a National Institute on Aging (NIA) grant A R01