To prevent the Samoan swallowtail butterfly from going extinct, we must increase our understanding of the butterfly’s interactions with other species.

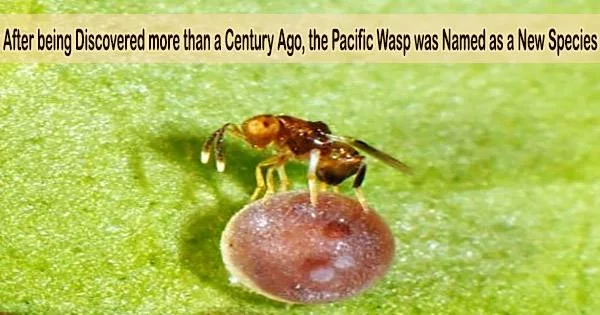

A new species of wasp has been hiding in plain sight for almost 140 years.

Living on the island of Tutuila in American Samoa, hints of Ooencyrtus pitosina’s existence to western science first came in 1885, when naval officer and entomologist Gervase Frederick Mathew first saw that a minute insect was attacking the eggs of the Samoan swallowtail butterfly.

Although the behavior’s specifics were documented in a scholarly journal, the wasp was never given an official description. In an effort to spur additional investigation into this little-known wasp, a team of researchers has finally completed this.

Dr. Andrew Polaszek, an entomologist at the Natural History Museum who led the research, says, “This might be a record for the length of time between identifying a species, and it later being described. It goes to show that describing a species is not as simple as just pointing at something you don’t recognize and giving it a name.”

“When Ooencyrtus pitosina was seen in the 1880s, there would have been great difficulty in identifying whether or not it was a new species. Its host was only formally described about 20 years earlier, so a lack of understanding of the butterfly would have hindered finding out about the wasp.”

The findings of the study were published in the journal PLOS One.

Samoa’s unique wildlife

Over 3,000 square kilometers of the Pacific Ocean are covered by the Samoan islands. Because of their remoteness, they are home to a number of species of animals and plants that are unique to them, like the tooth-billed pigeon and the Samoan starling.

The Samoan swallowtail butterfly, or Papilio godeffroyi, is another, and is one of just three species of this type of butterfly known in this region of the Pacific. It was originally widespread over the biggest Samoan islands, but today it is only found on Tutuila after going extinct on the other islands of the archipelago sometime in the late 1970s or early 1980s.

As the wasp is killing the butterfly, it initially seems like the wasp is the villain of the story. Without the wasp, however, it’s possible that the talafalu could be wiped out on the island by being consumed by high numbers of the swallowtail’s caterpillars. In fact, it’s helping to keep the ecosystem in balance by keeping the butterfly population in check. If the swallowtail larvae overwhelmed the trees, then they would lose their source of food and push themselves closer to extinction.

Dr. Andrew Polaszek

Today, it is found in just 5% of the range it lived in during the early 1970s. Although the reasons for the insect’s decrease are unknown, it is believed that human activity and tropical storms have destroyed the talafalu tree, which the Samoan swallowtail depends on for egg-laying.

These plants are equally as important to the parasitic wasp O. pitosina, which lays its own eggs inside those of the Samoan swallowtail. As its larvae emerge and begin to consume the butterfly eggs from the inside, adult wasps are finally produced.

While it may seem like the wasps are also contributing to the butterfly’s decline, Andrew argues that they’re performing a vital role.

“As the wasp is killing the butterfly, it initially seems like the wasp is the villain of the story,” Andrew says. “Without the wasp, however, it’s possible that the talafalu could be wiped out on the island by being consumed by high numbers of the swallowtail’s caterpillars.”

“In fact, it’s helping to keep the ecosystem in balance by keeping the butterfly population in check. If the swallowtail larvae overwhelmed the trees, then they would lose their source of food and push themselves closer to extinction.”

The destiny of the three distinct species of Tutuila is intertwined because of their close ties. With the Samoan swallowtail now classed as Endangered, it’s assumed that its loss would probably also lead to the extinction of O. pitosina.

Dr. Mark Schmaedick, a co-author of the research, adds, “While it seems likely that Mathew’s 1880s report of the egg parasitoid on P. godeffroyi in the Samoan islands and on the closely related Papilio schmeltzi in Fiji are both O. pitosina, there’s no way to check on that at the moment.”

“It’s difficult to say whether it does parasitize on more than just the Samoan swallowtail and whether it might occur outside the swallowtail’s range. We haven’t yet found any evidence that it does, but it also appears that the wasp might not be readily detected by typical general collecting methods.”

If the wasp went extinct, it would mean the extinction of multiple species. According to DNA analysis, it is not particularly linked to any other species of known wasp. While it’s likely that closer relatives simply haven’t been found yet, O. pitosina is currently the only example of this unique branch of the tree of life.

Fortunately, the wasp benefits from anything that helps it, just as the dangers to the Samoan swallowtail impact the wasp. Plans to reintroduce the Tutuila butterfly onto the islands of the neighboring country of Samoa must consider the wasp, which could help control its numbers.

The Samoan swallowtail and O. pitosina will need to be more understood than they are today in order for the reintroduction to be successful. The researchers intend to carry out more research the following year in an effort to prevent a sting in the tail for these two mutually exclusive species.