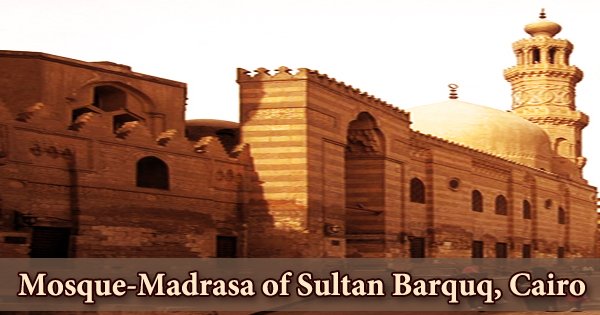

Mosque-Madrasa of Sultan Barquq or Mosque-Madrasa-Khanqah of Az-Zaher Barquq (Arabic: مسجد ومدرسة وخانقاه الظاهر برقوق), was erected in 1384/86 in Islamic Cairo, Egypt’s old medieval neighborhood, on Al Muizz El-Din Allah Street (Bayn El Qusrayn “between the Palaces”), a short walk from the Khan Khalili market area. It was built as a school for religious education in the four Islamic schools of thought by Sultan al-Zahir Barquq and consists of a mosque, madrasa, mausoleum, and khanqah. Madrasa is the Arabic word for “school,” and it refers to both a place of learning and a place of worship. It was the first architectural facility constructed during the Mamluk Sultanate’s Circassian (Burji) era. The complex is located in Muizz Street’s historic district. In the stretch of al-Mu’izz street known as Bayn al-Qasrayn, it comprises one of the grandest arrangements of Mamluk monumental architecture in Cairo, together with the Sultan Qalawun Complex and the Madrasa of al-Nasir Muhammad, with which it is contiguous. Sultan Barquq, the founder of the Burji or Circassian Mamluk dynasty, built his complex in the prized Bayn al-Qasrayn area between 1384 and 1386. Part of the construction was overseen by architect Shihab al-Din Ahmad ibn Muhammad al Tuluni, who came from a line of court architects and surveyors. In the inauguration inscription on the facade and in the courtyard, the name of Jarkas al Khalili, the master of Barquq’s horse and the founder of the famed Khan al Khalili, appears. He was trained at the Circassian military barracks in the citadel, as were many other mamluks at the period. Barquq rose to prominence in the state under Yalbugha, and with the violent deaths of Yalbugha and then Sultan Sha’ban, he became a significant figure in the time of instability and internal conflict that followed. Sultan Barquq attempted to legitimize his rule by linking himself with the previous dynasty, the Bahri Mamluks, to whom the tradition of repelling Crusaders and Mongols while adhering to Sunni Islam was passed down. He ordered the creation of a burial foundation for his family after establishing himself socially by marrying Baghdad Khatun, the widow of Sultan Sha’ban, one of Sultan Qalawun’s final relatives. He sought to place it adjacent to the early Qalawunid monuments on the prestigious al-Mu’izz Street to emphasize the continuity. Furthermore, as part of Bayn al-Qasrayn Street, the mosque is woven into the fabric of Egyptian society and inhabitants’ daily lives. In the 1970s, it served as a shelter for evicted families, which is one of its lesser-known functions. The street where the mosque is located has inspired many works of art and literature, the most notable of which is Naguib Mahfouz’s novel “Bayn al-Qasrayn” or palace walk. Many photos of the mosque may be seen in the background of the film, which was inspired by the novel.

The iwans (arched recesses) on the four sides of the courtyard were each dedicated to one of the four schools of Islamic teaching/law. On the higher floors, students and teachers were also given living spaces. The madrasa and cemetery complex of Barquq began in December 1384 (Rajab 786 in the Islamic calendar) and was completed in April 1386 (Rabi’ I 788), according to the inscription on its front. With its marble paneling, bronze-plate doors, molded stone embellishment, and intricately crafted minaret, Michael Rogers has proven that this complex set the tone for Cairene architectural decoration between 1400 and 1450. The overall architecture and decoration are similar to Sultan Hassan’s larger and earlier Mosque-Madrasa. The structure also houses a mausoleum, the dome of which may be seen from the street. The octagonal minaret departs from most minarets from this period in displaying a shaft with stone carving, which, in the 15th c., replaces the inlaid stonework characteristic of 14th c. minarets (e.g., Sarghatmish). Because building resources were scarce and valuable, the royal rank (blazon) is attached to common things and materials such as window plaster grilles and rough wood. A foundation inscription can be seen right below a row of muqarnas sculpted on the upper section of the wall, while another Qur’anic inscription can be found at a lower level around the doorway. The upper lines of letters in the Qur’anic inscription merge together into flower-like knots in an elegant and distinctive calligraphic style. The madrasa and mausoleum mihrabs are represented by the two-round windows visible along the external wall. The waqf deed, according to Doris Behrens-Abouseif, refers to this complex as a madrasa-khanqah and its living units as a rab’, a phrase that normally alludes to collective accommodation. The main prayer hall is designed in the basilica style, comparable to the madrasa in Qalawun’s complex, with columns supporting the roof. Marble mosaics and paneling embellish both the floor and the qibla wall (the wall that marks the direction of prayer). The mihrab-shaped marble mosaics covering the floor at the foot of the qibla wall are a rare and distinctive element. The main mihrab is surrounded by four ornate columns and adorned in multicolored marble tiles. The deed utilizes bayt, a term used interchangeably with khalwa in waqf documents to describe a living unit in a madrasa or khanqah, instead of tabaqa, the term for an individual living unit in a residential dwelling. The roundels above the mihrabs have wooden frames, but the windows surrounding the complex have stucco frames with tinted glass. As previously stated, Barquq was not ultimately buried here, although the chamber does contain the grave of one of his daughters, Fatima. Sufism’s absorption into urban life in fifteenth-century Egypt is seen in the inclusion of a Sufi curriculum to a madrasa.