A team lead by an assistant professor at The University of Alabama in Huntsville (UAH) has uncovered a small, uncommon crayfish that had been assumed to be extinct for 30 years in a cave in the City of Huntsville in northern Alabama.

In 2019 and 2020 trips into Shelta Cave, Dr. Matthew L. Niemiller’s team discovered individuals of the Shelta Cave Crayfish, scientifically known as Orconectes sheltae.

Dr. Niemiller, an assistant professor of biological sciences at the University of Alabama at Huntsville, is a co-author of an article published in the journal Subterranean Biology on the discoveries. Authors include Katherine E. Dooley and K. Denise Kendall Niemiller of UAH, as well as Nathaniel Sturm of the University of Alabama.

The National Speleological Society (NSS) owns and manages a 2,500-foot cave system that is unobtrusively hidden under the organization’s national headquarters in northwest Huntsville and is bordered by subdivisions and busy highways.

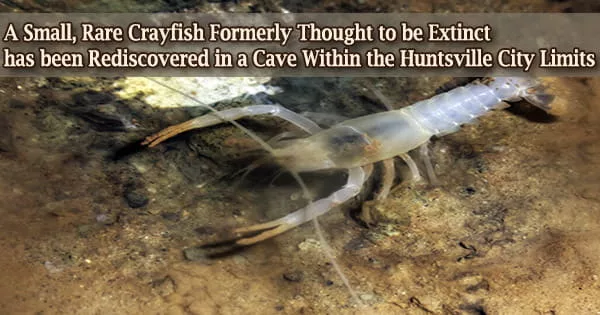

“The crayfish is only a couple of inches long with diminutive pincers that are called chelae,” Dr. Niemiller says. “Interestingly, the crayfish has been known to cave biologists since the early 1960s but was not formally described until 1997 by the late Dr. John Cooper and his wife Martha.”

For his dissertation work in the late 1960s and early 1970s, Dr. Cooper, a biologist, and speleologist who was a member of the NSS, investigated the water life in Shelta Cave, with a special concentration on crayfish. The water ecosystem of Shelta Cave was extremely rich at the time, with at least 12 cave-dependent species described, including three cave crayfish species.

“No other cave system to date in the U.S. has more documented cave crayfishes co-occurring with each other,” Dr. Niemiller says.

However, in the early 1970s, the aquatic environment, which included the Shelta Cave Crayfish, collapsed. The collision could be linked to a fence designed to keep people out of the cave while allowing a grey bat maternity population to freely enter and exit.

“The initial design of the gate was not bat friendly, and the bats ultimately vacated the cave system,” Dr. Niemiller says. “Coupled with groundwater pollution and perhaps other stressors, that all may have led to a perfect storm resulting in the collapse of the aquatic cave ecosystem.”

Groundwater is critically important not just for the organisms that live in groundwater ecosystems, but for human society for drinking water, agriculture, etc. The organisms that live in groundwater provide important benefits, such as water purification and biodegradation. They also can act like ‘canaries in the coal mine,’ indicators of overall groundwater and ecosystem health.

K. Denise Kendall Niemiller

The Shelta Cave Crayfish was never as common as the other two species, Southern Cave Crayfish (Orconectes australis) and Alabama Cave Crayfish (Cambarus jonesi), even before the fall in the aquatic cave population.

“To the best of our knowledge, only 115 individuals had been confirmed from 1963 through 1975. Since then, only three have been confirmed one in 1988 and the two individuals we report in 2019 and 2020,” Dr. Niemiller says.

“After a couple of decades of no confirmed sightings and the documented dramatic decline of other aquatic cave life at Shelta Cave, it was feared by some, including myself, that the crayfish might now be extinct.”

While the existence of the Shelta Cave Crayfish is encouraging, he claims that additional aquatic species that originally existed in the cave system, such as the Alabama Cave Shrimp and Tennessee Cave Salamander, have yet to be discovered.

“The groundwater level in Shelta Cave is the result of water that works its way naturally through the rock layers above the cave called epikarst from the surface,” says Dr. Niemiller. “However, urbanization in the area above the cave system may have altered rates at which water infiltrates into the cave and also increased rates of pollutants, such as pesticides and heavy metals entering the cave system.”

The crayfish was discovered again during an aquatic study aiming at documenting all of the cave system’s fauna.

“I really wasn’t expecting to find the Shelta Cave Crayfish. My students, colleagues and I had visited the cave on several occasions already leading up to the May 2019 trip,” Dr. Niemiller says. “We would be fortunate to see just a couple of Southern Cavefish and Southern Cave Crayfish during a survey.”

Dr. Niemiller observed a smaller cave crayfish below him while snorkeling in around 15 feet of water in North Lake in the Jones Hall part of the cave.

“As I dove and got closer, I noticed that the chelae, or pincers, were quite thin and elongated compared to other crayfish we had seen in the cave,” he says. “I was fortunate to swoop up the crayfish with my net and returned to the bank.”

It was a mature adult, measuring under an inch in carapace length and with developing ova inside.

“We noted some other morphological characters, took photographs, acquired a tissue sample and released the crayfish,” Dr. Niemiller says.

“The second Shelta Cave Crayfish that we encountered was in August 2020 in the West Lake area,” he says.

The team had searched a large portion of the area but had found little aquatic life. Nate Sturm, a master’s student in biology at the University of Alabama who had joined the lab on the excursion, observed a small white crayfish in an area where the crew had previously traveled through as they started to make their way out the lake channel to return to the surface.

“It was a male with thin and elongated chelae,” Dr. Niemiller says. “I had already walked ahead of the area and did not see the crayfish. Thank goodness for young eyes!”

To aid identification, the team analyzed short fragments of mitochondrial DNA in the tissue samples collected.

“We compared the newly generated DNA sequences with sequences already available for other crayfish species in the region,” Dr. Niemiller says. “A challenge we faced was that no DNA sequences existed prior to our study for the Shelta Cave Crayfish, so it was a bit of a process of elimination, so to speak.”

While few crayfish are deemed single-site endemics, meaning they only exist in one spot, cave-dwelling species like the Shelta Cave Crayfish are more likely to be, he says.

“A couple other cave crayfishes are known from single cave systems in the United States. A challenge we face when trying to conserve such species is determining whether they really are known from a single cave system, or might they have slightly larger distributions but we are hampered by our ability to study life underground.”

Little is known about the species’ life history and ecology outside of Dr. Cooper’s dissertation work.

“The Southern Cavefish (Typhlichthys subterraneus) and Tennessee Cave Salamander (Gyrinophilus palleucus) may be predators of smaller young of the Shelta Cave Crayfish. Larger Southern Cave Crayfish and Alabama Cave Crayfish might also feed on small young,” Dr. Niemiller says.

“We know nothing of the diet of the species, but it likely is an omnivore feeding on organic matter washed or brought into the cave, as well as small invertebrates such as copepods and amphipods.”

Dr. Niemiller is currently conducting the first-ever comprehensive assessment of groundwater biodiversity in the central and eastern United States, a pioneering search for new species and new understanding of the complex web of life that exists right beneath our feet, despite the fact that this research took place before the grant.

The research is supported by a five-year, $1.029 million CAREER award from the National Science Foundation (NSF). He believes it is critical to understand the health of communities of microscopic species that rely on groundwater.

“Groundwater is critically important not just for the organisms that live in groundwater ecosystems, but for human society for drinking water, agriculture, etc.,” Dr. Niemiller says. “The organisms that live in groundwater provide important benefits, such as water purification and biodegradation,” he says. “They also can act like ‘canaries in the coal mine,’ indicators of overall groundwater and ecosystem health.”