A single shot that could provide months-long protection against malaria has proven effective and safe in a small, early clinical trial of adults. The shot, which contains monoclonal antibodies, would primarily be intended for infants and children in countries with the most malaria transmission, the team who conducted the trial says. These young children have the highest risk of dying from severe malaria.

In the clinical trial, 15 of 17 participants who received the monoclonal antibodies did not become infected after being exposed to mosquitoes with malaria in the lab, the researchers report in the Aug. 4 New England Journal of Medicine. All six people who did not receive the medicine developed infections.

The clinical trial tested different doses and delivered the medicine intravenously or as a shot. Based on a computer model of how the medicine is taken up, distributed, and then cleared by the body, the researchers estimate that one shot may protect against malaria for six months.

“What we’ve always been looking for is some sort of intervention that will prevent infection reliably and for as long a time as possible,” says Miriam Laufer, a pediatric infectious disease doctor, and director of the Malaria Research Program at the University of Maryland School of Medicine in Baltimore.

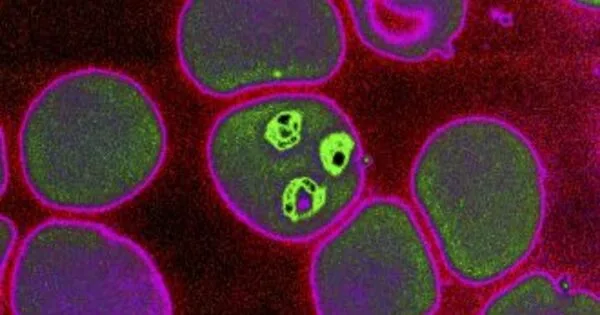

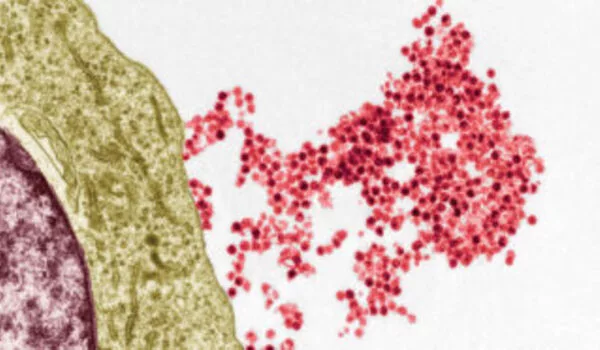

The antibody evaluated in the clinical trial attaches to a protein on the surface of sporozoites — the form of the malaria parasite that enters the body after an infected mosquito bites — and stops the parasites from infecting the liver.

Miriam Laufer

Ideally, Laufer says, that would be a highly effective vaccine that provides years and years of protection. A new malaria vaccine has recently become available, but it is only modestly protective against the disease, and that protection wanes rapidly. The vaccine requires four shots.

Monoclonal antibodies could provide an option that requires only one shot, once a year. It will take more research to see how well the antibodies work against malaria outside of the laboratory and how cost-effective the shot is.

The monoclonal antibodies shot wouldn’t exclude the need for other prevention strategies, says Laufer, who was not involved in the new study. But it could be “one of the easier interventions in terms of minimal contact with the health care system, with good benefit.”

What’s appealing, she says, “is the possibility that you could give kids, even the youngest kids, an injection [of] premade antibodies that could last for six months or longer and protect them throughout the rainy season.” That once-a-season shot would be helpful in countries in West Africa, where malaria transmission only occurs during the rainy season.

Malaria sickened an estimated 241 million people and killed 627,000 worldwide in 2020. Most of those deaths occurred in sub-Saharan Africa in children younger than 5. These littlest kids haven’t had the chance to develop immunity to the disease and are more susceptible to dying if severe malaria develops.

Reducing the spread of malaria includes measures to control mosquitoes, such as using insecticide-treated nets over beds or spraying to kill mosquitoes indoors, as well as preventing infections, such as taking antimalarial drugs at regular intervals. In October 2021, the World Health Organization also recommended the new vaccine, which in clinical trials reduced cases of malaria and severe malaria by 36 percent after four years of follow-up.

Monoclonal antibodies are a laboratory-made version of antibodies, the proteins that the immune system produces in response to a vaccine or natural infection. Monoclonal means that it contains clones, or copies, of one particular antibody.

The antibody evaluated in the clinical trial attaches to a protein on the surface of sporozoites — the form of the malaria parasite that enters the body after an infected mosquito bites — and stops the parasites from infecting the liver.

The new monoclonal antibody has improvements over an earlier version developed by the same research team. The new version binds more strongly to the targeted malaria parasite protein. It also has a tweak that keeps it from degrading too quickly in the body. This boosts its half-life in the blood (the time it takes for half of the medicine to degrade) to 56 days, almost three times that of its predecessor.

Two clinical trials are planned to assess how well the medicine protects children in places where malaria is spreading. One trial in Mali, where malaria transmission is seasonal, will study the shot’s efficacy over seven months. Another trial in Kenya, among the countries in East Africa where malaria spreads year-round, will assess how well the shot works while following the children for a year. Those studies will also help to determine the best dose for children.