Brown dwarfs are unusual celestial objects that are much heavier than planets but not massive enough to become stars. The celestial objects can be extremely hot (think thousands of degrees Fahrenheit), but these 95 newly discovered neighbors are surprisingly cool. According to the statement, some of these strange worlds are even relatively close to Earth’s temperature and may be cool enough to have water clouds in their atmospheres.

Brown dwarfs, mysterious objects that exist between stars and planets, are critical to our understanding of both stellar and planetary populations. Despite nearly three decades of searching, only 40 brown dwarfs could be imaged around stars. Using a novel search method, an international team directly imaged four new brown dwarfs.

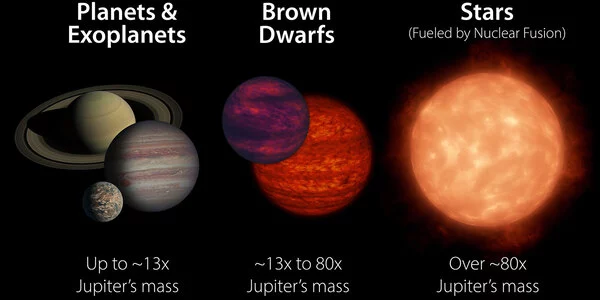

Brown dwarfs are mysterious astronomical objects with stellar and planetary characteristics that exist between the heaviest planets and the lightest stars. Because of their perplexing nature, these perplexing objects are critical to improving our understanding of both stars and giant planets. Brown dwarfs orbiting a parent star from a sufficient distance away are particularly valuable because they can be photographed directly, as opposed to those that are too close to their star and thus obscured by its brightness. This gives scientists a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to study the details of brown dwarf companions’ cold, planet-like atmospheres.

These findings significantly increase the number of known brown dwarfs orbiting stars at great distances, with a significant increase in detection rate compared to any previous imaging survey.

Mariangela Bonavita

However, despite remarkable efforts in the development of new observing technologies and image processing techniques, direct detections of brown dwarf companions to stars have remained rather sparse, with only around 40 systems imaged in almost three decades of searches. Researchers led by Mariangela Bonavita from the Open University and Clémence Fontanive from the Center for Space and Habitability (CSH) and the NCCR PlanetS at the University of Bern directly imaged four new brown dwarfs as they report in a study that has just been published in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society MNRAS. This is the first time that multiple new systems with brown dwarf companions on wide orbital separations have been announced at the same time.

Innovative search method

“Wide-orbit brown dwarf companions are extremely rare to begin with, and directly detecting them poses enormous technical challenges because the host stars completely blind our telescopes,” says Mariangela Bonavita. So far, most surveys have been conducted by randomly selecting stars from young clusters. “Another approach to increasing the number of detections is to only observe stars that show signs of an additional object in their system,” Clémence Fontanive explains. The way a star moves under the gravitational tug of a companion, for example, can be an indicator of the companion’s existence, whether it is a star, a planet, or something in between.

Clémence Fontanive continues, “We developed the COPAINS tool, which predicts the types of companions that could be responsible for observed anomalies in stellar motions.” Using the COPAINS tool, the researchers carefully selected 25 nearby stars that appeared promising for the direct detection of hidden, low-mass companions based on data from the European Space Agency’s Gaia spacecraft (ESA).

Observing these stars with the SPHERE planet-finder at the Very Large Telescope in Chile, they discovered ten new companions with orbits ranging from Jupiter to beyond Pluto, including five low-mass stars, a white dwarf (a dense stellar remnant), and four new brown dwarfs.

Major boost in detection rate

“These findings significantly increase the number of known brown dwarfs orbiting stars at great distances, with a significant increase in detection rate compared to any previous imaging survey,” says Mariangela Bonavita.

While this method is currently limited to brown dwarf and stellar companion signatures, future phases of the Gaia mission will push these methods to lower masses, allowing for the discovery of new giant exoplanets. “On top of having so many new discoveries in one go,” Clémence Fontanive adds, “our program also demonstrates the power of these search strategies.”

“This result was only possible because we believed that when space and ground-based facilities were combined to directly image exoplanets, the whole was greater than the sum of its parts. We hope that this marks the beginning of a new era of collaboration between various instruments and detection methods” Mariangela Bonavita wraps up.