The tropical Pacific Ocean’s islands were supposed to have been settled by people in two separate migrations starting around 3,330 years ago, covering tremendous distances.

The first left what is now the Philippines and traveled north, while the second left Taiwan and New Guinea and traveled south. Around 1,000 years later, people began to settle on the islands that make up the Federated States of Micronesia today.

However, a recent discovery by a Tufts sea-level researcher and his colleagues raises the possibility that the islands of Micronesia were populated considerably earlier than previously thought and that travelers on the two routes may have interacted. They published their findings in the PNAS publication.

Associate professor of Earth and Climate Sciences Andrew Kemp was lured to Micronesia to gather new data from the tropical Pacific Ocean, which is far less well known than the north Atlantic Ocean, to better understand how climate change affects global sea level change.

On the islands of Kosrae and Pohnpei in the Federated States of Micronesia, the study team gathered sediment cores from mangroves with assistance from the National Science Foundation.

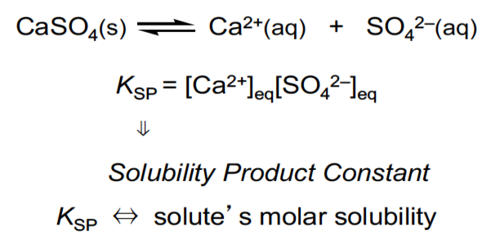

In Micronesia, where the islands are sinking, radiocarbon dating revealed that relative sea level rose significantly there over the past 5,000 years, by about 4.3 meters (14 feet), despite relative sea level, the height of the land relative to the height of the ocean next to it, falling across much of the tropical Pacific.

Even though the two islands are subsiding considerably more quickly than other islands in the Pacific, the researchers could plainly observe the results and their significance for comprehending how humanity managed to occupy remote Oceania.

The team including Juliet Sefton, then a postdoctoral researcher at Tufts and now an assistant lecturer at Monash University in Australia, and Mark McCoy, an associate professor of anthropology at Southern Methodist University was struck by the implications of relative sea level for interpreting the monumental ruins of Nan Madol, a large series of stone buildings constructed on islets separated by canals filled with ocean water just offshore from the island of Pohnpei.

We propose that Pohnpei and Kosrae perhaps weren’t settled anomalously late, but rather they were settled around the same time as the other islands in the Pacific. People arrived and lived at the coast, but subsidence of the islands caused relative sea level rise, which submerged the oldest archeological evidence. It’s probably underwater, yet to be found if it will ever be found.

Juliet Sefton

Long believed to have been administrative or religious structures built some 1,000 years ago for the island’s aristocracy to live separate from the rest of the population, the ruins are now a U.N. World Heritage site.

However, Kemp and his colleagues came to the conclusion that this assumption was false as a result of long-term relative sea-level increase. The buildings were on the island itself and weren’t separated by any water at the time they were erected.

According to McCoy, the prevailing description of Nan Madol as the “Venice of the Pacific” may not have been accurate when it was constructed.

It caused the scholars to consider the actual beginning of human settlement on these islands. Kemp points out that the maritime people who initially settled the islands would likely have resided along the coastline, which is why archaeologists look for evidence there but haven’t found any indicating earlier settlement.

“We propose that Pohnpei and Kosrae perhaps weren’t settled anomalously late, but rather they were settled around the same time as the other islands in the Pacific,” Sefton says. “People arrived and lived at the coast, but subsidence of the islands caused relative sea level rise, which submerged the oldest archeological evidence. It’s probably underwater, yet to be found if it will ever be found.”

The volcanic islands of Micronesia Kosrae, Pohnpei, Chuuk, and Yap may have served as a meeting place for people migrating north and south if that is the case.

Due to incorrect assumptions made by experts regarding the earliest time the islands were populated based on water levels, there has never been any proof of this. McCoy points out that archaeologists “have been looking in the wrong place for years, because we assumed that relative sea level was falling.”

“Although we can’t prove that there was interaction between these two pathways, we can present an argument that says the data that exists now about migration in the Pacific is probably a lot more incomplete than it is thought to be,” says Kemp.