According to new research undertaken by experts at the University of Bath’s Milner Centre for Evolution, identifying evolutionary trees of animals by comparing anatomy rather than DNA sequences is deceptive.

The study, which was published in the journal Communications Biology, demonstrates that we frequently need to contradict centuries of scholarly work that categorized living organisms based on their appearance.

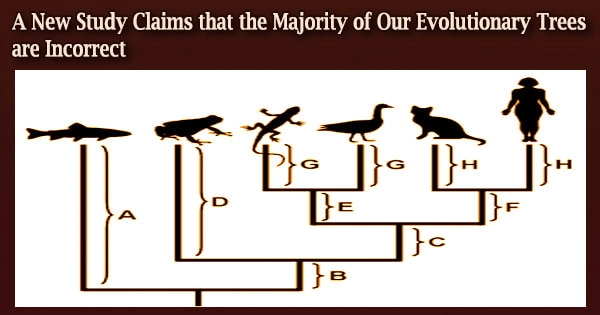

Biologists have been attempting to reconstruct animal “family trees” since Darwin and his contemporaries in the 19th century by carefully scrutinizing discrepancies in their anatomy and structure (morphology).

However, thanks to advances in rapid genetic sequencing techniques, biologists can now use genetic (molecular) data to piece together evolutionary relationships for species quickly and cheaply, revealing that organisms we once thought were closely related actually belong in completely different branches of the tree.

The interplay of changes in information and speciation has resulted in the Tree of Life. Life is diversified, as it is made up of many different species rather than just one. While there may have been just one line of descent at first, there are now multiple lines of descent, resulting in many “families” reproducing through time.

For the first time, scientists at the University of Bath compared evolutionary trees based on morphology to those based on DNA data, and mapped them according to geographic location.

They discovered that animals classified together by molecular trees lived geographically closer together than animals grouped by morphological trees. A phylogenetic tree can be viewed as a timeline of evolution. A single lineage at the base of many phylogenetic trees represents a common ancestor.

Matthew Wills, Professor of Evolutionary Paleobiology at the Milner Centre for Evolution at the University of Bath, said:

“It turns out that we’ve got lots of our evolutionary trees wrong. For over a hundred years, we’ve been classifying organisms according to how they look and are put together anatomically, but molecular data often tells us a rather different story. Our study proves statistically that if you build an evolutionary tree of animals based on their molecular data, it often fits much better with their geographical distribution.”

“Where things live their biogeography is an important source of evolutionary evidence that was familiar to Darwin and his contemporaries. For example, tiny elephant shrews, aardvarks, elephants, golden moles, and swimming manatees have all come from the same big branch of mammal evolution despite the fact that they look completely different from one another (and live in very different ways).

They’ve all been lumped together in a group called Afrotheria, so named since they all come from the African continent, and the group’s biogeography matches.

It turns out that we’ve got lots of our evolutionary trees wrong. For over a hundred years, we’ve been classifying organisms according to how they look and are put together anatomically, but molecular data often tells us a rather different story. Our study proves statistically that if you build an evolutionary tree of animals based on their molecular data, it often fits much better with their geographical distribution.

Professor Matthew Wills

The study discovered that convergent evolution, which occurs when a characteristic arises in two genetically unrelated groups of animals at the same time, is far more prevalent than biologists previously thought.

Professor Wills said: “We already have lots of famous examples of convergent evolution, such as flight evolving separately in birds, bats, and insects, or complex camera eyes evolving separately in squid and humans. But now with molecular data, we can see that convergent evolution happens all the time things we thought were closely related often turn out to be far apart on the tree of life.”

“People who make a living as lookalikes aren’t usually related to the celebrity they’re impersonating, and individuals within a family don’t always look similar it’s the same with evolutionary trees too.”

“It proves that evolution just keeps on re-inventing things, coming up with a similar solution each time the problem is encountered in a different branch of the evolutionary tree. It means that convergent evolution has been fooling us even the cleverest evolutionary biologists and anatomists for over 100 years!”

Dr. Jack Oyston, Research Associate and first author of the paper, said: “The idea that biogeography can reflect evolutionary history was a large part of what prompted Darwin to develop his theory of evolution through natural selection, so it’s pretty surprising that it hadn’t really been considered directly as a way of testing the accuracy of evolutionary trees in this way before now.”

“What’s most exciting is that we find strong statistical proof of molecular trees fitting better not just in groups like Afrotheria, but across the tree of life in birds, reptiles, insects, and plants too. It being such a widespread pattern makes it much more potentially useful as a general test of different evolutionary trees, but it also shows just how pervasive convergent evolution has been when it comes to misleading us.”