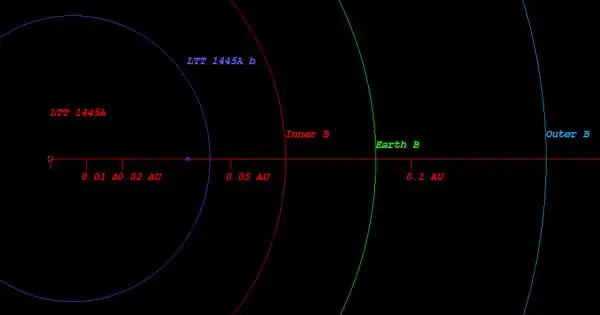

Under strange data, the standard model of cosmology, the theory that describes the world at enormous scales, is buckling. Distinct measurements of the Hubble Constant, the universe’s expansion rate, provide two different figures when only one should be found. There is no clear explanation for this “tension” at the moment, although physicists are working on it. A new theory proposes that there are many more particles out there, which form an unseen “mirror world” that runs through our cosmos. The scientists used a uniform scaling of gravitational free-fall rates and photon-electron scattering rates to toy with the model of the universe and reconcile data, as reported in the journal Physical Review Letters.

This corrects the inconsistency without interfering with anything else in the universe, but there is a catch. “Basically, we point out that many of the cosmological findings have an intrinsic symmetry when the universe is rescaled as a whole.” In a release, the main author Francis-Yan Cyr-Racine, an assistant professor in the Department of Physics and Astronomy at the University of New Mexico, stated, “This might give the means to understand why there appears to be a disagreement between different measurements of the Universe’s expansion rate.”

The presence of mirror matter is the caveat. The contemporary concept of mirror matter is only a few decades old. For basic particles, symmetry can take many forms. There is time reversal, which ensures energy conservation. The existence of antimatter is supported by charge symmetry. There’s also spatial symmetry, rotation, translation, and reflection to consider. The mirror reflection symmetry, commonly known as P-symmetry or parity, is ignored by elementary particles. They follow a combination CPT (Charge, Parity, Time) symmetry, but the parity break led some physicists to wonder if all known particles had a mirror counterpart.

While there is presently no proof that this is the case, this new research discovered that if this mirror matter exists, it would be possible to scale those rates and resolve the cosmological observations’ tension. “This scaling symmetry could only be achieved in practice by integrating a mirror world in the model — a parallel universe with new particles that are all duplicates of known particles,” Cyr-Racine explained. “The notion of a mirror world emerged in the 1990s, but it was not previously acknowledged as a possible solution to the Hubble constant problem.

“This may appear absurd at first glance, but such mirror worlds have substantial physics literature in a completely different context since they can aid in the solution of fundamental particle physics issues,” Cyr-Racine noted. “For the first time, our method allows us to connect this vast literature to an essential cosmological challenge.” However, the model is not yet the ideal answer. The team intends to keep working on it and find a means to restrict two more features that the model presently can’t satisfy: the quantity of helium and the hydrogen isotope deuterium at the beginning of the universe.