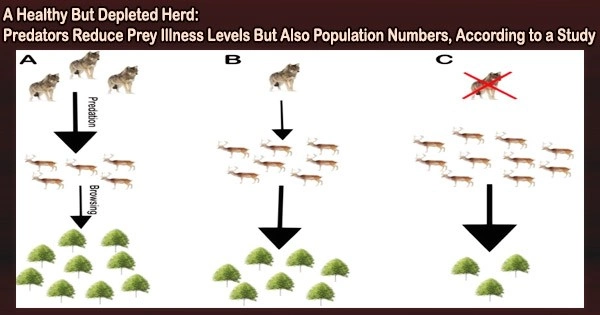

According to nature documentaries, lions, cheetahs, wolves, and other top predators target the weakest or slowest animals and that this culling improves prey herds, whether it’s antelope in Africa or elk in Wyoming.

For many years, biologists have universally accepted this theory, which was codified in 2003 as the healthy herds hypothesis. It suggests that predators can help prey populations by removing sick and damaged animals while leaving healthy, robust animals to breed.

The healthy herds concept has even been used to argue that managing predator numbers to protect prey could be an effective conservation technique. Even Nevertheless, hard evidence supporting the concept is limited, and many of its assumptions and predictions have been called into question in recent years.

A University of Michigan-led research team employed a pint-sized predator-prey-parasite system within 20-gallon water tanks to test the healthy herds hypothesis in a study published online April 26 (2023) in the journal Ecology.

Their study system consisted of predatory fly larvae that feed on the water flea Daphnia dentifera, which hosts a virulent fungal parasite.

While high predation levels reduced parasitism in Daphnia, providing partial support for the healthy herds hypothesis, the researchers discovered that populations of those poppy seed-sized crustaceans were frequently dramatically reduced as well. In some cases, Daphnia populations were nearly wiped out by predation.

Interestingly, intermediate predation levels reduced parasitism in our study without incurring a cost in terms of overall prey density. Any management decisions would need to weigh the potential costs and benefits associated with increasing predation.

Meghan Duffy

According to the study’s authors, the findings may have ramifications for conservation efforts involving much larger creatures. The findings suggest that wildlife managers should exercise caution when manipulating predator numbers in the goal of promoting healthy herds of prey.

“The appeal of the healthy herds hypothesis lies in the alignment of multiple conservation goals simultaneous conservation of predators, reduction of parasitism, and protection of vulnerable populations as well as the potential to reduce spillover risk to other populations, including humans,” said U-M aquatic and disease ecologist Meghan Duffy.

“But even when predators reduce disease in their prey populations, that does not necessarily lead to increased prey population size, as our study shows,” said Duffy, senior author of the new study and a professor in the U-M Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology.

The extermination of badgers in the United Kingdom to minimize bovine tuberculosis in livestock is one well-known example of “healthy herds” gone wrong. In that situation, culling can be considered as a very efficient kind of human predation.

The rationale underlying those programs was that increased badger predation, which is a wildlife reservoir of bovine tuberculosis, would result in healthy livestock herds. Instead, the initiatives promoted cow TB.

In another case, culling bats to minimize rabies spread has not been beneficial in lowering rabies in domestic canines or animals.

Findings of the new study, and others like it, could help explain why some attempts to control disease by manipulating predators fail, according to the authors.

“Unless we develop a more comprehensive understanding of when and how predators influence disease, management strategies that propose to reintroduce or augment predator populations could backfire,” said study lead author Laura Lopez, a former postdoctoral researcher in Duffy’s lab who now works for the National Centre for Immunisation Research and Surveillance in Australia.

For nearly 20 years, Duffy has utilized Daphnia as a model organism to examine the causes and implications of infectious disease outbreaks, including multiple investigations of the healthy herds hypothesis.

The researchers conducted the newest study by manipulating the density of a predator in their three-organism study system, then monitoring Daphnia population sizes and infection levels.

The predators were larvae of the phantom midge, which commonly prey on Daphnia in North American temperate lakes. The parasite was the virulent fungus Metschnikowia bicuspidata.

The predator-prey-parasite interactions occurred inside 48 experimental water tanks called mesocosms, which also contained nutrients and green algae.

At the highest levels, predation completely eliminated the fungal pathogen. However, the highest predation levels frequently reduced Daphnia population sizes, which contradicts the healthy herds hypothesis.

“If your primary concern is the overall population size of a vulnerable animal species, then adding high levels of predation that eliminate disease could be detrimental,” Duffy said. “Interestingly, intermediate predation levels reduced parasitism in our study without incurring a cost in terms of overall prey density. Any management decisions would need to weigh the potential costs and benefits associated with increasing predation.”

The authors of the Ecology study cautioned that obtaining and sustaining a level of predation that minimizes parasitism while not reducing prey population size “might be equivalent to threading the proverbial needle.”