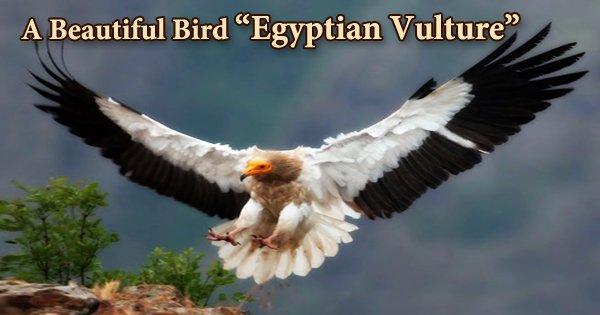

The Egyptian vulture (Neophron percnopterus), also known as the white scavenger vulture or pharaoh’s chicken, is a solitary or pair-bonding bird that can congregate in large groups at feeding sites or shared night roosts. It is the only member of the Neophron genus and a small Old World vulture. These birds can be found all over southern Europe, northern Africa, and western Asia. They prefer dry plains and will primarily nest in rocky hilly areas. Soaring in thermals with other scavengers, this species is often seen. The Canary and Cape Verde Islands have isolated populations. While Egyptian vultures are not true migrants, they do migrate between their breeding and resident areas more than most other vultures. Breeding pairs can stay at the same nesting site for several years in a row. As it soars in thermals during the warmer parts of the day, the contrasting underwing pattern and wedge-shaped tail make it stand out in flight. Egyptian vultures eat mostly carrion, but they will also eat small rodents, insects, and reptiles if the opportunity arises. They also eat other birds’ eggs, cracking larger ones with a huge pebble thrown onto them. They can travel up to 80 kilometers per day in search of food. They are opportunistic feeders, meaning they can consume a wide variety of foods. They have white adult plumage and black feathers on their wings and tail. Owing to the bird’s habit of stalking around a carcass, waiting its turn, on dusty land, the plumage dulls easily, and the feathers are more beige than pure white before a molt. Individuals can also cover themselves with soil containing iron oxide, which turns their plumage pinkish buff and earns them the German name Schmutzgeier (“dirt-vulture”). Tools are unusual in birds, and Egyptian vultures use twigs to roll up wool for use in their nest, in addition to using a pebble as a hammer.

In the twentieth century, the population of this species declined, and some island populations are threatened by hunting, accidental poisoning, and collisions with power lines. Despite the fact that these vultures are not true migrants, they fly between their breeding and resident areas more often than most other vultures. This species prefers arid open areas including steppe, desert, cereal fields, and pastures, but it needs rocky nesting sites. They are often found near human settlements, such as in or near cities, as well as near slaughterhouses, garbage dumps, and fishing ports. The bill has a black tip and is narrow. The deep-fingered black flight feathers contrasted with white inner feathers in flight may remind you of a White Stork, but the tail is wedge-shaped. The faces of the juveniles are bare gray and dirty brown. An open-air or semi-open-air creature that nests on cliffs and less often in trees. From the tip of the beak to the end of the tail feathers, an adult Egyptian vulture measures 47–65 centimeters (19–26 in). Males of the smaller N. p. ginginianus measure 47–52 centimeters (19–20 in) in length, while females measure 52–55.5 centimeters (20.5–21.9 in). The wingspan is approximately 2.7 times the length of the body. Birds from Spain weigh around 1.9 kilograms (4.2 lb), while birds from the Canary Island subspecies majorensis, which represents an example of island gigantism, weigh 2.4 kilograms on average (5.3 lb). The bulk of its diet consists of carrion, which includes dead birds, small rodents, cattle, and large wild animals. After other vultures have eaten the bulk of the soft flesh from large carcasses, it will also prey on the scraps. They will also eat rotting fruit, vegetables, and even excrement, and will sometimes prey on small animals, particularly those that are sick or wounded, such as rabbits, chicks, spawning or dying fish, and some insects. The Egyptian vulture eats eggs as well and will throw stones at them to crack open the shell, a fascinating and uncommon example of bird tool use. Egyptian vultures can be found breeding all over the Old World, from southern Europe to northern Africa, and east to western and southern Asia. This species has a hard time maintaining flapping flight and does well when it takes off from a high vantage point or uses thermal updrafts on a warm plain. When more suitable breeding sites are inaccessible, this vulture species is known to nest in trees or old buildings. Egyptian vultures prefer open terrain with a wide range of elevations. Migrating birds will fly 500 kilometers (310 miles) in a single day to reach the Sahara’s southern edge, which is 3,500 to 5,500 kilometers (2,200 to 3,400 miles) from their summer home. The male will perform swooping displays for his partner during mating, and the two will engage in talon grappling during courtship. The breeding season varies a little depending on the population and location, but eggs are usually laid between March and May. In most cases, two eggs are laid, and both parents incubate them for 39-45 days. Both the male and female feed their chicks before they are ready to leave the nest 70 to 85 days after hatching. The chicks are self-sufficient at about 4 months of age. Chicks can be seen flying in their home range with their parents after they have fledged. When migration from the breeding grounds begins, they abandon their parents; they attain maturity at the age of six. Egyptian vultures are visual hunters who do not use their sense of smell to find food. They mainly search for food in open areas where carcasses can be found from a great height. In ancient Egyptian religion, the bird was considered sacred to Isis. The vulture’s use as a symbol of royalty in Egyptian culture, as well as their defense under Pharaonic rule, made the species popular on Egyptian streets, earning it the nickname “pharaoh’s chicken.”