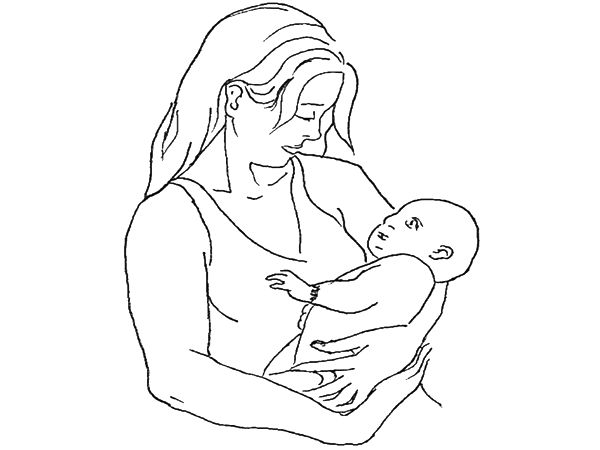

Maternal depression is thought to be a risk factor for children’s socioemotional and cognitive development. Researchers from the Maudsley Biomedical Research Centre (BRC) investigated whether depression, either before or during pregnancy, affects the mother-infant relationship in a study funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). The study was published in BJPsych Open.

Researchers examined the quality of mother-infant interactions in three groups of women: healthy women, women with clinically significant depression in pregnancy, and women with a lifetime history of depression but healthy pregnancies.

The study included 131 women: 51 healthy mothers with no current or past depression, 52 mothers with depression who were referred to the South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust Perinatal Psychiatry Services, and 28 ‘history-only’ mothers who had a history of depression but no current diagnosis. Children who are exposed to maternal depression in their early years of life are at a higher risk of developing socioemotional difficulties and psychopathology later in life.

Research has found that women with depression during pregnancy, or with a history of depression, had a reduced quality of mother-infant interaction at both eight weeks and 12 months after their babies were born.

Quality of interaction

Mothers and babies in the depression and history-only groups had lower interaction quality at eight weeks and 12 months. At eight weeks, 62 percent of mothers with depression during pregnancy and 56 percent of mothers with a history of depression scored in the lowest category of relationship quality, where therapeutic interventions are recommended, compared to 37 percent in the healthy group. Between 8 weeks and 12 months, all mother and baby groups improved in their quality of interaction, indicating that with time, all mothers and their babies can become more attuned to each other, according to the researchers.

New-born babies of mothers in the depression and history-only groups had decreased social-interactive behavior at six days, which, along with maternal socioeconomic difficulties, was also predictive of a lower quality of interaction, whereas postnatal depression was not.

Dr. Rebecca Bind, lead author and Research Associate at King’s College London’s Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology, and Neuroscience, says: “Our findings suggest that perinatal mental health professionals should provide support not only to pregnant women who are depressed but also to pregnant women who have a history of depression, as they may also face interaction difficulties. Future research should look into why a history of depression, despite a healthy perinatal period, may have an impact on the developing relationship.”

Senior author Carmine Pariante, Professor of Biological Psychiatry at King’s College London’s Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology, and Neuroscience, and Consultant Perinatal Psychiatrist at the South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust, stated:

“We recommend that healthcare professionals provide examples of positive caregiving behaviors, as well as ways to engage their babies and understand their needs, to pregnant women at risk of interaction difficulties, all of which could be incorporated into parenting and birth classes and health visits.” We also believe that interventions that can improve mother-infant interaction, such as video feedback, in which a clinician and mother discuss what behaviors work best to engage and comfort the baby, and structured mother-baby activities, such as art and singing groups, should be made more widely available. This is especially important because we know that the early years are vital for future mental health and wellbeing.”

The Crittenden Child-Adult Relationship Experimental-Index was used to assess the relationship between mothers and infants, which measures ‘dyadic synchrony,’ a term that describes the overall quality of the relationship. The researchers examined three-minute interactions recorded at eight weeks and 12 months postnatally. Researchers scored the relationship based on seven aspects of behavior: facial expression, vocal expression, position and body contact, affection and arousal, turn-taking contingencies, control, and choice of activity.

The researchers are grateful to the women and their infants who participated in the PRAM-D study and to everyone on the study team who recruited, collected, and analyzed data.