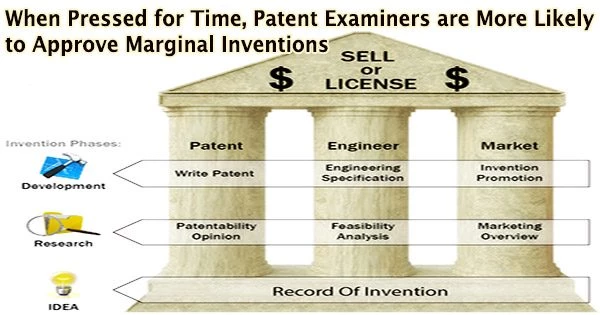

As the saying goes, haste makes waste. The same aphorism might be extended to the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, where high-ranking examiners have a propensity to rubber-stamp applications of doubtful validity owing to time restraints, according to research by a University of Illinois expert in patent law.

The less time patent examiners are given to review an application, the more likely they are to grant patent protection to inventions “on the margin,” says a study co-authored by Melissa Wasserman, the Richard and Anne Stockton Faculty Scholar and Richard W. and Marie L. Corman Scholar at the College of Law.

“Patent quality is at the heart of patent reform debate,” Wasserman said. “It is generally agreed that the patent office is allowing too many invalid patents, which is bad for society for a number of reasons, including that these patents may actually impede rather than promote innovation. Congress and the courts have recognized this, and have been trying to tweak the patent system in an effort to increase patent quality. Essentially, they’ve been trying to help the patent office do a better job.”

“But until now, there’s been very little compelling empirical evidence that any particular feature of the patent office has been causing them to over-grant and thereby allow invalid patents.”

With the help of the National Center for Supercomputing Applications, Wasserman and co-author Michael D. Frakes of the Northwestern University School of Law performed a data analysis on 1.4 million patent applications considered by the office from 2002 to 2012. They cross-referenced their findings with examiner roster information received from the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office via a series of FOIA requests.

“For a lot of the information we gathered, the only source is the patent and trademark office, which has become a lot more open to researchers and academics in recent years,” Wasserman said.

The study’s findings revealed that each pay step-up an examiner received was followed by resulted in a 10- to 15% reduction in the time allotted for reviewing patent applications. According to the study, examiners working at the highest level were expected to review an application in roughly half the time allotted to examiners working at the lowest level.

Our findings provide empirical evidence for policymakers to utilize to increase patent quality. That is, we find how the patent office decreases the time allocated to review applications as patent examiners are promoted may be partially responsible for the agency granting too many invalid patents. If patent examiners are already pressed for time and the time allocated to review an application is further decreased, it is likely that examiners will spend less time searching the prior art, and that’s going to make it harder for them to figure out which patents are really new, and which ones represent just a trivial advancement over current scientific understanding.

Melissa Wasserman

The findings show that time allotments are pushing higher ranked patent examiners to grant invalid patents, the researchers claim, on the premise that patent examiners who are given enough time to evaluate applications will, on average, make the right patentability determinations.

“Our findings suggest that the process of promoting patent examiners, which is meant to reward admirable behavior on the part of examiners, may, in part, be responsible for the agency issuing patents of marginal quality,” Wasserman said. “It also sheds some light on the widely held belief that decreasing patent examiner attrition or intensifying the monitoring of newly hired examiners is vital to increasing patent quality.”

The study claims that if an examiner is given less time to analyze an application, they become less likely to look for prior art, which, in turn, reduces the likelihood that the examiner will reject an application on the basis of prior art. In particular, “obviousness” rejections, which are especially time-intensive, decrease, Wasserman said.

“Our findings provide empirical evidence for policymakers to utilize to increase patent quality,” she said. “That is, we find how the patent office decreases the time allocated to review applications as patent examiners are promoted may be partially responsible for the agency granting too many invalid patents. If patent examiners are already pressed for time and the time allocated to review an application is further decreased, it is likely that examiners will spend less time searching the prior art, and that’s going to make it harder for them to figure out which patents are really new, and which ones represent just a trivial advancement over current scientific understanding.”

“And this is how they’re going to end up granting more. They’re just not given enough time to look through everything that has already been created and invented to determine whether or not the claimed invention is really new or non-obvious.”

Lack of time, according to Wasserman, whose research focuses on the institutional design of innovation policy with a focus on administrative law and patent law in particular.

“In general, I think the office is right: As you get better at your job, you will likely be able to do it faster,” she said. “It’s just that our results suggest that the scaling of time allocations may be too aggressive. There may be just some set amount of time that’s needed to search the prior art, and once you decrease time allocations below this number, patent examiners are not going to be able to do a good job, no matter how good of an examiner they are.”

The research has implications for “patent assertion entities,” otherwise known (and pejoratively referred to) in the media as “patent trolls,” Wasserman said.

“To the extent so-called patent trolls are asserting invalid patents, our results suggest one reason as to why the office is issuing these marginal patents,” she said.

The research also points to another potentially troubling conclusion: Similar patent applications are sometimes treated in dissimilar ways.

“In an ideal world, a patent should be granted or rejected solely on the merits of the application,” Wasserman said.

“But it turns out that the decision to allow a patent may be more happenstance based on which examiner gets assigned your application. If you have two individuals, you and a competitor, and your competitor gets assigned a high-ranked examiner, and you get a low-ranked examiner, it’s more likely that your competitor is going to get their patent approved than you, which creates an unfair advantage.”