The fact that climate change’s consequences aren’t always linear is arguably its most worrisome feature. Increased temperatures invariably result in more of the recent uptick in fires, floods, and droughts. However, sometimes an increase in warmth might lead to a tipping point, from which an area or the entire world cannot readily recover even if temperatures dropped once more. According to a recent study, if we go over the 1.5°C (2.6°F) threshold, we’ll probably hit five of them.

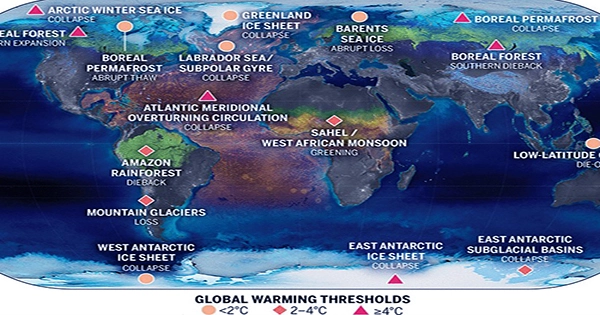

Although climate scientists are in agreement that tipping points do exist, they are much less certain of their ability to estimate the temperatures at which they will occur. The best estimates and the ranges of uncertainty for nine tipping points with global relevance and seven with significant regional significance are revealed in a report published in Science, which draws on 220 previously published studies.

Given the wide breadth of the investigation, it is not surprising that the news is conflicting. One thing is certain, though: if we don’t want to change the globe in ways that make recovery nearly difficult, we either need to keep the rise in temperature below 1.5° C, or count on being extremely, exceedingly lucky.

The tipping points that are discussed include topics that frequently grab the attention of people all across the world, such the Amazon becoming grassland and Greenland melting. Others are considerably less well recognized, like the alteration of convection currents in the Labrador Sea, but they all have effects that go beyond their immediate region.

Climate experts are certain they know how much global warming it will take to melt the ice in the Barents Sea to the point where it will be difficult to replenish it, as the accompanying figure demonstrates. Since less sea ice results in more sunlight being absorbed rather being reflected, even if the planet slightly cooled down again, the localized increase in temperatures would stop the trend. If temperatures remain 1.6°C (2.9°F) above pre-industrial levels over an extended period of time, this will happen. 1.1°C has already been exceeded and 1.5°C is drawing near.

In other situations, though, we’re like individuals hesitantly stepping into a landmine-filled field; we’re aware of their presence and the potential for destruction but unsure of how far we can advance before being detonated.

The Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation ceasing is the area of greatest uncertainty (AMOC). Warm water traveling northward along the Gulf Stream is predicted to dwindle to a trickle without the sinking of salty cold water that drives AMOC. The climate in the areas surrounding the Atlantic Basin may suffer as a result. A 4-degree increase is thought to be the most probable moment at which AMOC would reach its tipping point. It is now believed to be more likely than not that such a large temperature spike won’t occur.

The issue is that the level of uncertainty is so high that AMOC may tip at a temperature of less than 2 degrees, and every tenth of a degree of warming means we’re playing with increasingly loaded cards. Five of the 16 points under consideration are already outside the uncertainty range.

According to senior author Dr. David McKay of the Stockholm Resilience Center, “We can see symptoms of destabilization already in portions of the West Antarctic and Greenland ice sheets, in permafrost zones, the Amazon rainforest, and potentially the Atlantic overturning circulation as well.”

“There are already some places where the globe might tip. Additional tipping points are possible if the global temperature continues to climb. The possibility of reaching tipping points can be decreased by promptly beginning to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.”

The study also highlights two additional aspects that are difficult to depict mathematically or visually in graphs like the one above. The initial point is that not all of these impacts are only influenced by temperature. The trip wire may be much colder than the anticipated 3.5°C if the Amazon is being cleared for livestock pastures.

Furthermore, although some are more tied to one another than others, the tipping points are not wholly independent of one another.

Cascading tipping points are a substantial additional issue, according to Professor Ricarda Winkelmann of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research. “Many tipping factors in the Earth system are interrelated,” she added. The crucial temperature thresholds beyond which individual tipping elements start to become destabilized over time can actually be lowered via interactions, according to the study.