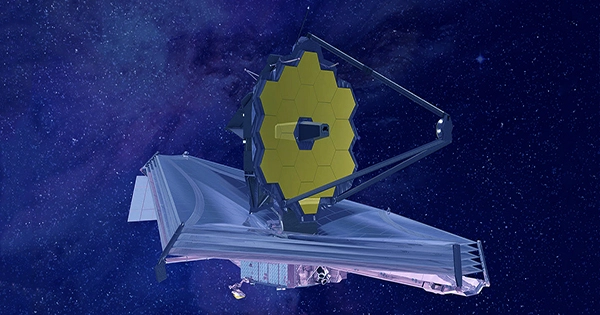

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) is presently on its nerve-wracking trip to orbit the Sun, and thanks to the Virtual Telescope Project, you can watch it go through the stars. After several delays and problems, the JWST – the world’s largest, most costly, and most powerful space observatory –launched on the morning of December 25. Astrophysicist Gianluca Masi of the Virtual Telescope Project observed the equipment travelling through orbit using a robotic telescope four days after it launched.

The JWST was around 550,000 kilometers (341,754 miles) from Earth at this time, roughly 1.5 times the normal lunar distance. It will not arrive at its final destination until late January 2021 – L2, the second Lagrangian Point, 1.5 million kilometers (932,056 miles) immediately “behind” the Earth as seen from the Sun. This voyage, on the other hand, will not be simple.

“Getting Webb to its orbit around L2 is like reaching the top of a hill enthusiastically pedaling just at the very beginning of the climb, producing enough energy and speed to spend the most of the trip coasting up the hill, slowing to a stop and barely arriving at the top,” NASA explained.

It will have an amazing perspective of the cosmos once it arrives at its final location, and it will begin learning about the development of the earliest galaxies and possibly habitable exoplanets. Keep an eye out for updates. The Virtual Telescope Project will see the JWST from the ground and transmit it live on January 7, 2022, at 9:30 p.m. UTC. That broadcast may be found here.

The James Webb Space Telescope will not orbit the Earth in the same manner as the Hubble Space Telescope does; instead, it will orbit the Sun 1.5 million kilometers (1 million miles) distant from the Earth at the second Lagrange point, or L2. This orbit is unique in that it allows the telescope to remain aligned with the Earth while it orbits the Sun. This permits the enormous sunshield on the satellite to shield the telescope from the Sun’s and Earth’s light and heat (and Moon).

Webb is especially interested in infrared light, which may perceive as heat. The telescope must insulate from any bright, hot sources since it will be viewing the very weak infrared emissions of very distant objects. This applies to the satellite as well! Not only does the sunshield protect the delicate mirrors and equipment from the Sun and Earth/Moon, but it also protects the spacecraft bus. The telescope will be functioning at a temperature of around 225 degrees below zero Celsius (minus 370 Fahrenheit). The temperature differential between the hot and cold sides of the telescope is enormous; on the hot side, you could practically boil water, while on the cold side, nitrogen would freeze!