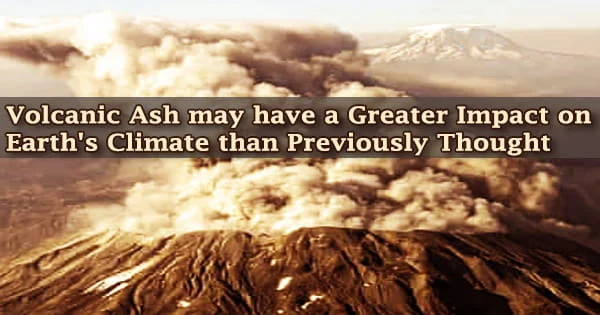

When volcanoes erupt, these geologic monsters produce tremendous clouds of ash and dust plumes that can blacken the sky, shut down air traffic and reach heights of roughly 25 miles above Earth’s surface.

Volcanic ash is a mixture of rock, mineral, and glass particles ejected by volcanoes during eruptions. The particles have a diameter of less than 2 millimeters. They have a low density since they are pitted and full of holes.

Volcanic ash is part of the dark ash column that rises above a volcano as it erupts, along with water vapor and other hot gases. According to a recent study done by the University of Colorado Boulder, volcanic ash may have a greater impact on the planet’s climate than previously thought.

The new study looks at the 2014 eruption of Mount Kelut (or Kelud) on the Indonesian island of Java, which was published in the journal Nature Communications.

The scientists determined that volcanic ash appears to be prone to loitering in the air for months or even longer following a significant eruption, based on real-world observations and powerful computer simulations.

“What we found for this eruption is that the volcanic ash can persist for a long time,” said Yunqian Zhu, lead author of the new study and a research scientist at the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics (LASP) at CU Boulder.

Volcanic ash is a potentially dangerous byproduct of volcanic explosions. Ash clouds shower down on the surrounding areas, covering the ground in feet of ash in some cases. The surface of areas near the volcano has been reported to be covered with 5-7 feet of ash. Fine ash particles can be carried away from the eruption site by the wind, causing harm to nearby populations.

Lingering ash

The discovery was made by chance: members of the study team were flying an unmanned aircraft near the site of the Mount Kelut eruption, which blanketed most of Java in ash and forced many to flee their homes. The aircraft noticed something that shouldn’t have been there during the operation.

“They saw some large particles floating around in the atmosphere a month after the eruption,” Zhu said. “It looked like ash.”

Scientists have long recognized that volcanic eruptions can have a negative impact on the planet’s climate, she explained. Large amounts of sulfur-rich particles are blasted high into the atmosphere, obstructing sunlight from reaching the earth.

Researchers have assumed that ash is similar to volcanic glass. But what we’ve found is that these floating ones have a density that’s more like pumice.

Yunqian Zhu

Volcanic ash can also generate thunderstorms and, if carried far enough into the atmosphere, it can deflect sunlight, lowering temperatures on Earth and causing a volcanic winter.

However, scientists do not believe that ash plays a significant part in the cooling impact. Scientists reasoned that because these chunks of rocky debris are so heavy, they will most likely fall out of volcanic clouds soon after an eruption.

Zhu’s team was curious as to why Kelut’s situation was different. The scientists discovered that the volcano’s plume appeared to be teeming with small and lightweight ash particles that were likely capable of floating in the air for lengthy periods of time, similar to dandelion fluff, based on airplane and satellite images of the unfolding disaster.

“Researchers have assumed that ash is similar to volcanic glass,” Zhu said. “But what we’ve found is that these floating ones have a density that’s more like pumice.”

Disappearing molecules

These pumice-like particles also appear to change the chemistry of the entire volcanic plume, according to study co-author Brian Toon.

Sulfur dioxide is emitted by erupting volcanoes, according to Toon, a professor in LASP and the Department of Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences at CU Boulder.

Many scientists previously considered that such molecules interact with other molecules in the air and through a series of chemical processes that may take weeks to complete. Observations of real-life eruptions, on the other hand, imply that it happens far faster.

“There has been a puzzle of why these reactions occur so fast,” Toon said.

He and his colleagues believe they’ve found the solution: Those sulfur dioxide molecules appear to cling to the ash particles floating in the air. They may undergo chemical reactions on the ash’s surface, potentially removing around 43 percent more sulfur dioxide from the atmosphere.

In other words, ash may hasten the atmospheric transformation of volcanic gases.

It’s unclear what effect the ash clouds will have on the climate. After an eruption, long-lasting particles in the atmosphere might darken and possibly help to chill the planet.

Floating ash from places like Kelut might also blow all the way to the planet’s poles. It might spark chemical reactions there, causing damage to Earth’s vital ozone layer.

However, one thing is apparent, according to the researchers: when a volcano erupts, it may be time to pay much closer attention to all that ash and its genuine impact on Earth’s climate.

“I think we’ve discovered something important here,” Toon said. “It’s subtle, but it could make a big difference.”