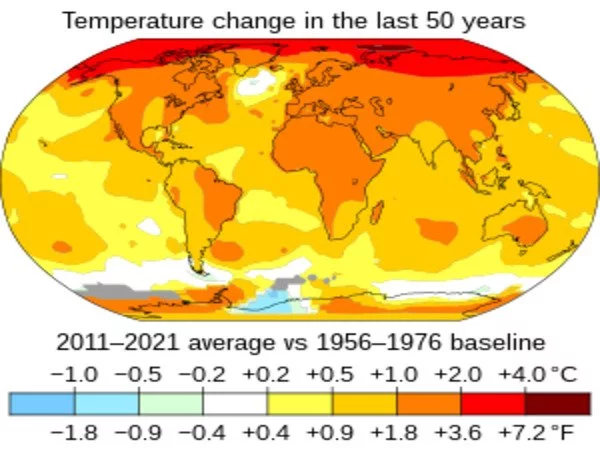

In the spring, India and Pakistan experienced extremely high temperatures. Researchers paint a bleak picture of the rest of the century in a new scientific journal article. Heat waves are expected to become more common, affecting up to half a billion people in South Asia each year.

Climate change is a reality, and India and Pakistan have reported extremely high temperatures in the spring. In a new scientific journal article, researchers from the University of Gothenburg, among others, paint a bleak picture for the rest of the century.

Heat waves are expected to become more common, affecting up to half-billion people each year. When temperatures rise above what humans can tolerate, they can cause food shortages, deaths, and refugee flows. According to the researchers, this does not have to happen if measures are put in place to meet the Paris Agreement targets.

Heat waves with temperatures above 40 degrees Celsius in the shade are a directly life-threatening form of extreme weather in India and Pakistan. Researchers have outlined various scenarios for the consequences of heat waves in South Asia up to the year 2100 in a new article published in the journal Earth’s Future.

We discovered a link between extreme heat and population growth. In the best-case scenario, we met the Paris Agreement’s targets of adding roughly two heat waves per year, exposing approximately 200 million people to the heat.

Deliang Chen

“We discovered a link between extreme heat and population growth. In the best-case scenario, we met the Paris Agreement’s targets of adding roughly two heat waves per year, exposing approximately 200 million people to the heat. However, if countries continue to contribute to the greenhouse effect as they are now, clearing and building on land that is actually helping to lower global temperatures, we believe that by the end of the century, there could be up to five more heat waves per year, with more than half a billion people exposed to them “According to Deliang Chen, Professor of Physical Meteorology at the University of Gothenburg and one of the article’s authors.

Population growth drives emissions

The study identifies the Indo-Gigantic Plains beside the Indus and Ganges rivers as particularly vulnerable. This is a region of high temperatures, and it is densely populated. Deliang Chen points out that the link between heat waves and population works in both directions. The size of the population affects the number of future heat waves. A larger population drives emissions up as consumption and transport increase. Urban planning is also important. If new towns and villages are built in places that are less subject to heat waves, the number of people affected can be reduced.

“We hope that regional leaders like India and Pakistan read and consider our report. The range for the number of people who will be exposed to heat waves in our calculation model is large. The actual numbers will be determined by the path these countries choose in their urban planning. The number of people who are actually exposed will be determined by future greenhouse gas and particulate emissions. We can more than halve the population exposed to extreme heat if we reduce emissions to meet the Paris Agreement’s targets. Both mitigation and adaptation strategies can make a significant difference” Deliang Chen says

Risk of a refugee wave

Heat waves are already causing major problems in India and Pakistan. Farmers have been hit hard when drought and heat has caused their wheat crops to fail, and their crops have moved to higher altitudes to escape the extreme heat. But this move has resulted in large acreages of trees being cleared; trees that have contributed to lowering temperatures.

“With a larger population, land use increases, which in itself can drive up temperatures further. Each heat wave will result in increased mortality and decreased productivity, since few people can work in 45-degree heat. I fear that if nothing is done, it can ultimately lead to a huge wave of migrations.”

Facts: Heat wave

In the study, a heat wave is defined as a temperature that is at least as high as the 10% of the region’s hottest summer days between 1975 and 2014. The authors of this study also used daytime temperatures above 35 degrees Celsius and nighttime temperatures above 25 degrees Celsius for at least three consecutive days as threshold values to map heat waves. A heat wave lasts about ten days, and unlike in Sweden, there is no significant cooling at night. The temperature is consistently high. The population is also acclimatized to varying degrees to a specific temperature and humidity.