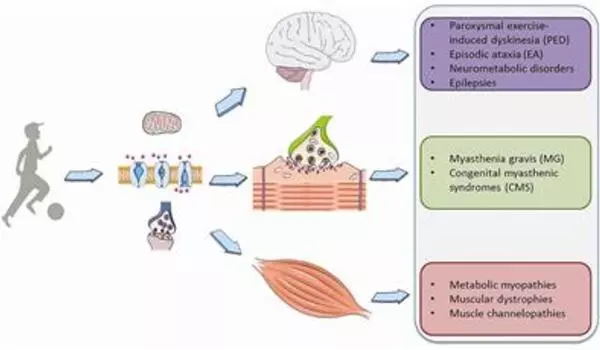

Children with movement disorders have involuntary movements or have difficulty moving in the way they intend. The term “movement disorders” is broad and encompasses a wide range of conditions with a wide range of causes. While children with paralysis also have difficulty moving, movement disorders differ in that the abnormal movements are “extra” or added on to movements that children intend to make.

Movement disorders can affect a single or multiple parts of the body, and their location and severity can change over time. The abnormal movements may occur on their own or only when the child is moving or attempting to make a specific type of movement. Sometimes the movements are more apparent at certain times of day or have specific triggers or situations that make them worse.

Spinal cerebellar ataxia 6 (SCA6) is an inherited neurological condition that impairs motor coordination. Because SCA6 affects only about one in 100,000 people, medical researchers have paid it little attention. There is currently no known cure and only a few treatment options.

Now, a group of McGill University researchers specializing in SCA6 and other forms of ataxia have published findings that not only offer hope to SCA6 patients, but may also pave the way for the development of treatments for other movement disorders.

The researchers discovered that exercise increased levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), a naturally occurring substance in the brain that supports nerve cell growth and development. Importantly, for patients with movement disorders who may not always be able to exercise, the team demonstrated that a drug that mimicked the action of BDNF could work just as well, if not better, than exercise.

Exercise in a pill

The McGill team, led by biology professor Alanna Watt, discovered that exercise improved the health of cells in the cerebellum, a region of the brain implicated in SCA6 and other ataxias.

The researchers discovered that exercise increased levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), a naturally occurring substance in the brain that supports nerve cell growth and development. Importantly, for patients with movement disorders who may not always be able to exercise, the team demonstrated that a drug that mimicked the action of BDNF could work just as well, if not better, than exercise.

Movement disorders can result from many types of brain injury, such as head trauma, infection, inflammation, metabolic disturbances, toxins, or unintended side effects of medications. They can also be a symptom of other, underlying diseases or conditions, including genetic disorders.

Early intervention crucial

Functional disorders also can occur in children with other neurological problems and make an existing movement disorder worse. The good news is most children recover from this type of movement disorder with retraining by physical therapists and continued supportive care from a neurologist. Children with functional neurological disorders benefit from joined care with a psychologist or psychiatrist.

The researchers also discovered that BDNF levels in SCA6 mice decreased well before movement difficulties appeared. They discovered that the drug only worked to stop the decline if it was given prior to the onset of visible symptoms.

“That’s not something we really knew about SCA6,” said lead author Anna Cook, a Ph.D. candidate in Professor Watt’s lab. “If there are these early changes in the brain that people aren’t even aware of, it tends to advocate for more genetic screening and early intervention for these rare diseases.”