The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) lists species that are at risk of extinction on its renowned Red List of Threatened Species.

A new machine learning tool for assessing extinction risk is presented in a study by Gabriel Henrique de Oliveira Caetano at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Israel, and colleagues. They then use this tool to demonstrate that reptile species that are unlisted due to a lack of data or assessment are more likely to be threatened than assessed species.

The most thorough assessment of a species’ extinction danger is provided by the IUCN’s Red List of Threatened Species, which guides global conservation practices and policy.

Although the process of classifying species is time-consuming and prone to bias, it mainly relies on manual curation by human experts. As a result, many animal species have not been assessed or do not have enough data, leaving gaps in protective measures.

These researchers developed a machine learning computer model to assess 4,369 reptile species that were previously unable to be prioritized for conservation and establish precise methods for measuring the extinction danger of cryptic species.

The 40% of the world’s reptiles that lacked published assessments or were categorized as “DD” (“Data Deficient”) at the time of the study were given IUCN extinction danger categories by the model. By comparing the model’s accuracy to the danger classifications on the Red List, the researchers verified its validity.

The IUCN Red List underrepresents the number of threatened species, and the researchers discovered that threatened status was more likely to exist for unassessed (“Not Evaluated” or “NE”) and data-deficient reptiles than for evaluated species.

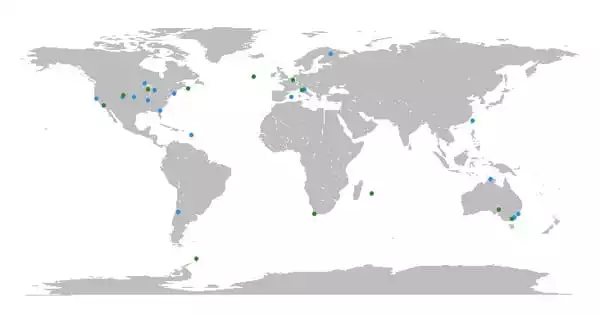

Importantly, the additional reptile species identified as threatened by our models are not distributed randomly across the globe or the reptilian evolutionary tree. Our added information highlights that there are more reptile species in peril especially in Australia, Madagascar, and the Amazon basin all of which have a high diversity of reptiles and should be targeted for extra conservation effort.

Shai Meiri

Future research is necessary to better comprehend the precise variables influencing the danger of extinction in threatened reptile taxa, to gather better information on obscure reptile taxa, and to develop conservation strategies that take newly discovered, threatened species into account.

According to the authors, “Altogether, our models predict that the state of reptile conservation is far worse than currently estimated, and that immediate action is necessary to avoid the disappearance of reptile biodiversity.”

“Regions and taxa we identified as likely to be more threatened should be given increased attention in new assessments and conservation planning. Lastly, the method we present here can be easily implemented to help bridge the assessment gap on other less known taxa.”

Coauthor Shai Meiri adds, “Importantly, the additional reptile species identified as threatened by our models are not distributed randomly across the globe or the reptilian evolutionary tree. Our added information highlights that there are more reptile species in peril especially in Australia, Madagascar, and the Amazon basin all of which have a high diversity of reptiles and should be targeted for extra conservation effort.”

“Moreover, species rich groups, such as geckos and elapids (cobras, mambas, coral snakes, and others), are probably more threatened than the Global Reptile Assessment currently highlights, these groups should also be the focus of more conservation attention.”

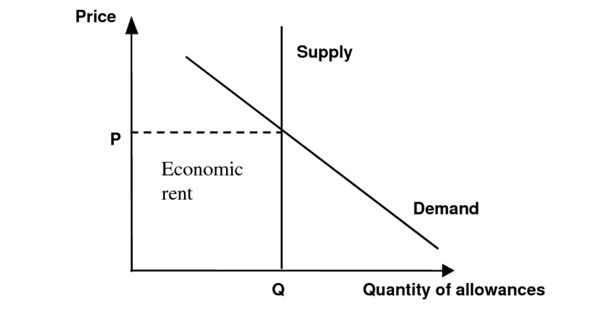

Coauthor Uri Roll adds, “Our work could be very important in helping the global efforts to prioritize the conservation of species at risk for example using the IUCN red-list mechanism. Our world is facing a biodiversity crisis, and severe man-made changes to ecosystems and species, yet funds allocated for conservation are very limited.”

“Consequently, it is key that we use these limited funds where they could provide the most benefits. Advanced tools- such as those we have employed here, together with accumulating data, could greatly cut the time and cost needed to assess extinction risk, and thus pave the way for more informed conservation decision making.”