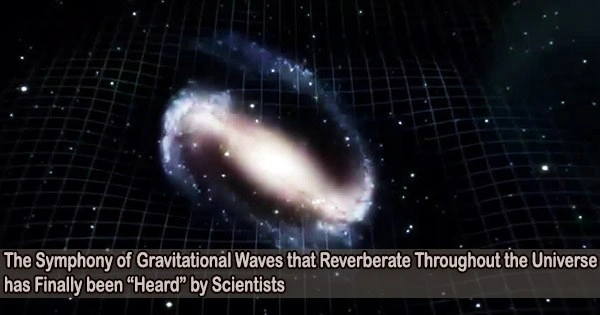

For the first time, scientists have seen the subtle ripples produced by the motion of black holes, which are gradually stretching and compressing the entire universe.

They claimed on Wednesday (July 2, 2023) that they had been able to “hear” the so-called low-frequency gravitational waves, which are caused by massive objects travelling through space and colliding.

“It’s really the first time that we have evidence of just this large-scale motion of everything in the universe,” said Maura McLaughlin, co-director of NANOGrav, the research collaboration that published the results in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

According to Einstein, as extremely heavy things move through the spacetime fabric that makes up our world, they cause ripples to form across the fabric. These vibrations have been compared by scientists to the cosmic soundtrack on occasion.

In 2015, scientists used an experiment called LIGO to detect gravitational waves for the first time and showed Einstein was right. But so far, those methods have only been able to catch waves at high frequencies, explained NANOGrav member Chiara Mingarelli, an astrophysicist at Yale University.

“Those quick ‘chirps’ come from specific moments when relatively small black holes and dead stars crash into each other,” Mingarelli said.

In the latest research, scientists were searching for waves at much lower frequencies. These sluggish waves, which cycle up and down over years or even decades, are most likely produced by supermassive black holes, which have billions of times the mass of the sun.

Galaxies across the universe are constantly colliding and merging together. Scientists think that while this occurs, the massive black holes at the centers of these galaxies also join together and engage in a dance before collapsing into one another, explained Szabolcs Marka, an astrophysicist at Columbia University who was not involved with the research.

As they move in these pairs, called binaries, the black holes emit gravitational waves.

“Supermassive black hole binaries, slowly and calmly orbiting each other, are the tenors and bass of the cosmic opera,” Marka said.

It’s really the first time that we have evidence of just this large-scale motion of everything in the universe.

Maura McLaughlin

No instruments on Earth could capture the ripples from these giants. So “we had to build a detector that was roughly the size of the galaxy,” said NANOGrav researcher Michael Lam of the SETI Institute.

The findings from NANOGrav, which has been looking for waves using telescopes across North America for 15 years, were presented this week. Other gravitational wave hunting teams throughout the world, including those in Europe, India, China, and Australia, also published studies.

The researchers focused telescopes on pulsars, which are dead stars that revolve around in space like lighthouses and emit radio wave bursts.

These bursts are so regular that scientists know exactly when the radio waves are supposed to arrive on our planet “like a perfectly regular clock ticking away far out in space,” said NANOGrav member Sarah Vigeland, an astrophysicist at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. However, gravitational waves actually alter the distance between Earth and these pulsars, disrupting their regular rhythm. They do this by stretching the fabric of spacetime.

Scientists were able to determine that gravitational waves were flowing through by examining minute variations in the ticking rate of several pulsars, with some pulses arriving slightly early and others arriving late.

The NANOGrav team monitored 68 pulsars across the sky using the Green Bank Telescope in West Virginia, the Arecibo telescope in Puerto Rico and the Very Large Array in New Mexico. Other teams found similar evidence from dozens of other pulsars, monitored with telescopes across the globe.

So far, this method hasn’t been able to trace where exactly these low-frequency waves are coming from, said Marc Kamionkowski, an astrophysicist at Johns Hopkins University who was not involved with the research.

Instead, it’s revealing the constant hum that is all around us like when you’re standing in the middle of a party, “you’ll hear all of these people talking, but you won’t hear anything in particular,” Kamionkowski said.

“The background noise they found is ‘louder’ than some scientists expected,” Mingarelli said. This may indicate that there are more or larger black hole mergers taking place than previously believed, or it may indicate the presence of additional gravitational wave sources that raise new questions about the nature of the universe.

The larger things in our universe are some of the topics that researchers aim to learn more about as they continue to investigate gravitational waves. It could open new doors to “cosmic archaeology” that can track the history of black holes and galaxies merging all around us, Marka said.

“We’re starting to open up this new window on the universe,” Vigeland said.