Medical privacy in forensic samples is a complex issue that raises important ethical, legal, and practical concerns. DNA, fingerprints, and other biological evidence are frequently collected as part of criminal investigations to identify suspects, victims, or link individuals to crimes. While the primary goal of collecting these samples is to aid in the investigation of crimes, there are concerns about how the collected data may be used and whether it may jeopardize an individual’s medical privacy.

If you watch any episode of “CSI,” you’ll see a character use forensic DNA profiling to identify a criminal. Contrary to what the legal community has believed for nearly 30 years, a new study from San Francisco State University suggests that these forensic profiles may indirectly reveal medical information, possibly even that of crime victims. The findings may have ethical and legal consequences.

“The main assumption when selecting those [forensic] markers was that there would be no information about the individuals other than identification. Our paper calls that assumption into question,” said first author Mayra Bauelos (B.S., ’19), who began working on the project as an undergraduate at San Francisco State and is now a Ph.D. student at Brown University.

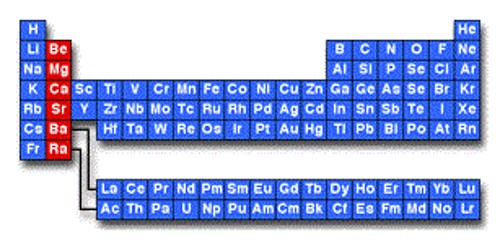

The Combined DNA Index System (CODIS) is a system that organizes criminal justice DNA databases and uses specific genetic markers to identify individuals. National, state, and local crime labs contribute to these databases by providing profiles based on samples collected from crime scene evidence, convicted offenders, felony arrestees, missing persons, and other information. The database can be used by law enforcement to try to match samples discovered during an investigation to profiles already stored in the database.

The main assumption when selecting those [forensic] markers was that there would be no information about the individuals other than identification. Our paper calls that assumption into question.

Mayra Bauelos

CODIS profiles are made up of an individual’s genetic variants as a set of short tandem repeats (STRs), which are DNA sequences that repeat at different frequencies among individuals. Since the 1990s, 20 STRs have been selected for forensic CODIS profiling because it was thought they did not relay medical information. If these profiles contained any trait information, medical privacy concerns could arise.

“But that assumption hasn’t been investigated in a long time, and we know a lot more about the genome now than we did back then,” said Rori Rohlfs, Associate Professor of Biology at SF State and project leader.

The assumption that only criminals are sampled is also not completely accurate. “It actually also includes victims of crime and people that may have been at crime scenes. You have these huge databases including a lot of people that are not necessarily criminals,” Bañuelos said. “I believe also that accessibility to these databases varies a lot according to a jurisdiction.”

Other papers have found associations between other (non-CODIS) STRs and disease or gene expression, according to the researchers. With this in mind, the SF State researchers wanted to learn more about the relationship between CODIS STR markers and gene expression.

Rohfls’ lab investigated the relationship between CODIS markers and gene expression using publicly available data (1000 Genome Project) and genetic models. They discovered six associations between CODIS markers and gene expression of nearby genes in white blood cell lines from more than 400 unrelated individuals in the database, out of the 20 CODIS markers.

“In some genes, gene expression change has been associated with medical conditions,” Bañuelos explained, citing prior research. “[In this study,] we indirectly know there is an association between these CODIS genotypes and some change in genes that can lead to illness.”

The authors highlight three particularly intriguing gene associations (CSF1R, LARS2, and KDSR). Previous research has linked CSF1R mutations and changes in gene expression to psychiatric disorders (depression and schizophrenia). Mutations and changes in gene expression in other genes have been linked to Perrault syndrome, MELAS syndrome, severe skin and platelet conditions, and other conditions, according to the researchers in the PNAS (Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences) paper. If CODIS markers are linked to the expression of genes associated with disease and health, then the data in the CODIS database may jeopardize an individual’s medical privacy.

“Our paper in some ways is like the tip of the iceberg,” Rohlfs said, admitting that she was surprised to find associations in a relatively small sample size. The project itself simply started as an undergraduate exploration project. Eight of the 11 authors were, like Bañuelos, undergraduates at SF State when the project began.

“It raises the question: If we did a more expansive [genetic] study, would we find even more information that would be revealed by CODIS profiles?” Rohlfs asked.

Baelos and Rohlfs want to know what they’d find if they looked at a larger dataset with more diverse populations – their current dataset is primarily European. Their investigation was also restricted to white blood cells. What kinds of connections would they discover if they looked in other tissues?

Because the current dataset does not represent the general population, these are critical lines of inquiry. Furthermore, Latino and African American communities are overrepresented in CODIS databases, according to Bauelos.

More research is needed to better understand the relationship between CODIS and medical information. However, the researchers warn that if CODIS profiles contain medical information, there could be serious consequences.